|

||||||||||||

|

July/August 2016

BY GREGORY McNAMEE

So it was that Spec.4 Doug Peacock, fresh from organizing civil rights demonstrations at the University of Michigan, became a medic in the Army Special Forces, a unit that—thanks to Staff Sergeant Barry Sadler’s “Ballad of the Green Berets”—was fast becoming a byword for crazy-tough bravery and independence. Peacock was no stranger to adventure or outdoor living. He had spent his youth exploring the rugged forests of the Upper Peninsula. While in college studying anthropology, he worked with archaeologists in the far northern reaches of Alaska. He was already a devotee of the dry, desolate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau, and he packed some impressive muscles on a small frame, born of walking everywhere and, as he recounts, “pounding nails on hot roofs in Phoenix and Tucson during the summer vacations” to earn tuition money. At the same time, he was reading and writing poetry, listening to rock and roll, and enjoying campus life, though with a difference—where others listened to the newly electric Bob Dylan and smoked a little grass between seminars, Peacock was inviting people such as Martin Luther King, Jr., and Tom Hayden to turn his fellow students’ energies toward changing the world. He graduated and went west. “The draft caught up with me when I was lazily hanging around Berkeley, not taking enough credit units to be a full-time graduate student,” Peacock recalls. “I got the letter and I volunteered. I was intrigued by the Green Beret medical program, which basically taught you how to be a doctor in a year without any BS—you don’t have courses on malpractice, but you sure learn what to do in the field. I probably would have gone to medical school if I hadn’t been in the service, for this reason: In my world, you don’t want to depend on the outside, and you want to be able to take care of yourself and your own.” Peacock’s world, by that time, had come to take in big swaths of the wilderness of the western United States, places full of beauty and not a little danger—not unlike the Central Highlands of Vietnam. “I volunteered right after I got out of Special Forces school,” he says. “I landed in ’Nam and got to work. I built a small hospital and trained some nurses, and we always had a steady flow of customers. Too many.” He was a born leader—perhaps a curious thing for someone who describes himself as a loner and an anarchist. Peacock says being a Green Beret medic out in Hre Montagnard country—often operating alone and without much supervision—was the perfect assignment for “an anarchist with an inclination to go native.” He saw terrible action, patched up hundreds of injured Vietnamese and Americans, and served on A-teams scores of miles from the nearest help. Though not far from Da Nang as the crow flies, Peacock’s Vietnam might as well have been on a different planet. “I loved it,” he says, “the people, the countryside. It was beautiful. If it hadn’t been for the war, it might have been perfect, but the war always wound up getting in the way.” It got in the way when, on tunnel detail, Peacock encountered corpses “folded up into little fetal-like bundles, just like the prehistoric Indian burials I had found in Michigan as a teenager.” It got in the way in the buildup to the 1968 Tet Offensive, when, he recounts, an air strike on an overrun position killed dozens of children being herded across a river by advancing Viet Cong. “That was too much,” he says. “Too much.” A Green Beret sergeant major sized him up and ordered him out of the field to a hospital in Da Nang, where he was recovering from wounds when Tet itself began. Peacock excused himself without leave and headed back for the Highlands. He again tended to wounded Montagnards, then returned to Da Nang and, in essence, quit, as he already was overdue to rotate home. “Headquarters was glad to get me out of there,” he writes in his 1990 memoir Grizzly Years. “I had been out in the boonies too long and everyone knew it but me.” He was stateside four days later, confused and angry, and at a loss about what to do next.

Peacock’s last stop before going to Vietnam in 1966 had been a camping trip in the mountains of southern Arizona, where, he recalls, he saw mountain lion and black bear tracks that reminded him of what awaited him in the wild. When he returned, his evac helicopter flew over the in-progress scene of what came to be known as the My Lai Massacre. Peacock returned to the backcountry “to regroup and pull my life together,” as he puts it. He stayed there forever after, choosing first to defend not Montagnard people but the grizzly bears of the Bob Marshall Wilderness Area of Montana, a place where those big bears are feared more than welcomed. Over the years he became good friends with an older writer and World War II veteran named Edward Abbey, a leading voice in the Western environmental movement, and found himself—not entirely willingly, he adds—enlisted as a character, Hayduke, in Abbey’s comic 1975 novel of “ecosabotage,” The Monkey Wrench Gang. In time, partially under Abbey’s influence, Peacock became a writer himself. After Abbey died in 1989, Peacock began to write in earnest, finishing his memoir and a book about Baja California, the Mexican region that harbors some of the wildest desert territory in North America. After years of journeys, solo and with a few friends, into wild places that, he smilingly says, are full of things that “can kill you and eat you,” the very definition of wildness, he wrote a second memoir, Walking It Off, in 2005. There, having wrestled with post-traumatic stress and the ghosts of the past, he sized up his experiences in country. “I wouldn’t trade my time in Vietnam for anything,” he says. “The war prepared me, hardened me, for the only life I wanted or that I felt was subsequently possible.”

One consequence of his years of environmental work is the founding of an organization called Round River Conservation Studies, which works across North America on a variety of initiatives. Through activism and scientific work alike, Peacock says, RRCS has been instrumental in preserving 30 million acres of wilderness. He also works with veterans of Vietnam and subsequent wars, bringing soldiers on skis into the Yellowstone country in winter, for example, to do wildlife and ecological surveys. Recently, RRCS organized a project in Namibia to protect rhinoceros populations there, work carried out in large part by veterans of the war in Afghanistan. Hundreds of vets have participated in other events he’s organized in just the last few years. Not bad for an anarchist and loner. “I keep a hand in lots of projects,” he says, “in my own gnarly way.” When he’s not writing—his most recent book is In the Shadow of the Sabertooth, which draws on his years of research in anthropology and archaeology—Peacock keeps active in the environmental movement, seeking through a Round River initiative, for example, to declare the Bears Ears buttes of southeastern Utah a national monument. But Peacock also is careful to reserve time for himself, heading out into the wild desert country of southern Arizona on the trail of bighorn sheep and mountain lions, and into the deepest reaches of Alaska and the northern Rocky Mountains to commune with his beloved grizzly bears—the creatures, he says, that saved him after Vietnam. It’s telling that Doug Peacock’s webpage identifies him, in order, as a “veteran, writer, naturalist, and filmmaker.” Almost half a century after seeing action in Vietnam, Peacock still thinks of that time often, though the bitterness and dislocation he felt in the aftermath have subsided. “It takes a toll,” he notes of that anger, adding, “It lasted too long.” He’s endured stress and a bad ticker—but, he says, “I’m still here.” At the same time, he’s got more on his to-do list than most men half his age. At 74, he’s eager to get a knee replacement; tired, he says, of hobbling around on a cane. “I’ve got to get back into the mountains this summer,” he says. If sheer will and downright cussedness have anything to do with it, he’ll make it to the high country with no problem.

Charles Figley did a few atypical things during his tour of “My interest in human development and trauma was born from being with those kids,” Figley said recently. That interest led Figley to study human development as an undergraduate at the University of Hawaii, and go on to earn graduate degrees from Penn State (an M.S. in 1971 and a Ph.D. in 1974), and to join the faculty of Purdue University’s Department of Child Development and Family Studies. It also led to Figley becoming a pioneering researcher in the study of Vietnam veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder.

“We now know that experiencing trauma is about memory management and the consequent stress reactions. I then applied these principles to understanding how people are traumatized by and recover from tornadoes, then family violence, community violence, and now torture trauma.” In 1977 Figley established the Family Research Institute to study military families, as well as celebrity families, and the families of the U.S. hostages in Iran. In 1978 he wrote Stress Disorders Among Vietnam Veterans, which helped recognize PTSD as a psychological condition for the first time. He co-founded the Society for Traumatic Stress Studies and the online journal Traumatology. He has published more than 200 scholarly works, including 20 books and 114 peer-reviewed journal articles. His work focuses primarily on stress and the resiliency of individuals, families, and communities. In 2004 Figley was awarded a senior Fulbright Research Fellowship to conduct research in Kuwait. VVA will honor Charles Figley, the director of the Tulane Traumatology Institute at Tulane University, with our VVA Excellence in the Sciences award at the National Leadership & Education Conference in Tucson. It’s been a year of firsts for Henry Threadgill. When the renowned jazz composer, saxophonist, and flautist received the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for music in May, it marked the first time a Vietnam veteran took home that prestigious award. Threadgill became the first war veteran to receive the music prize since World War II and only the third African-American jazz artist to get the music Pulitzer, joining Wynton Marsalis and Ornette Coleman. Threadgill, who will receive the VVA Excellence in the Arts Award at the National Leadership & Education Conference in Tucson, was born in Chicago. He studied at the American Conservatory of Music there, majoring in composition, along with piano and flute. He became a professional musician before he was twenty years old in the mid-sixties. With the draft breathing down his neck, the young, talented musician joined the Army in 1966, signing up for a musician’s MOS as a clarinetist-saxophonist. In his first post-training assignment at Fort Riley the new recruit wrote and arranged music for Army concert and marching bands. Then came orders for the war zone. Threadgill arrived in country in 1967 and joined the 4th Infantry Division Band. He plied his musical craft, but Threadgill and his bandmates also had to pull plenty of guard duty and occasionally were sent into the bush carrying rifles. Threadgill was seriously injured during Tet ’68 when the jeep he was riding in took fire and crashed. He finished his tour of duty later that year and received his honorable discharge. Henry Threadgill came home from Vietnam, and embarked on a long and distinguished career. He has been composer in residence at the University of California, Berkeley and the Atlantic Center of the Arts. As a bandleader, he has fronted many groups including Air, the Sextett, Very Very Circus, the twenty-piece Society Situation Dance Band, and his current group, Zooid. He has released thirty critically acclaimed albums and has been hailed by The New York Times as “perhaps the most important jazz composer of his generation.” Henry Threadgill’s awards include a Guggenheim Fellowship, a 2009 Aaron Copland Award, five Down Beat Magazine International Jazz Critics Poll Best Composer Awards, and the Jazz Journalists Association Composer of the Year Award in 2002. Kimo Williams, the musician who received the VVA Excellence in the Arts Award four years ago, described Henry Threadgill as “a master musician who surely deserves accolades for his contributions to the arts. We both served in Vietnam and returned to express ourselves through music. Through this recognition from Vietnam Veterans of America, I am honored to be associated with him as a fellow brother in arms and music.” Threadgill looks back at his time in the Army as a positive experience. “Many people think ‘artist’ means ‘fragile’,” he said recently, “but you can’t be fragile and survive as an artist if you want to stay true to your vision. Besides, being artists didn’t stop any of us from serving in wartime.”

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

||||||||||||

In November 1966 a young man from a small town in the middle of Michigan found himself in Vietnam attached to a combat team at a hamlet called Thuong Duc. He had come there, in a way, by accident. Like so many others, he had graduated from college only to find himself facing the draft. Wanting at least some measure of choice over his destiny and not inclined to run, he elected to follow the hardest course of action.

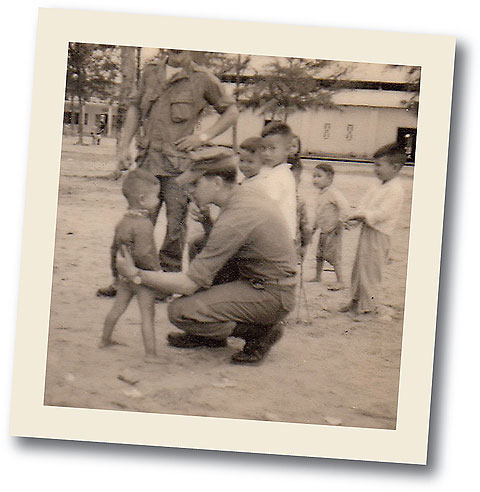

In November 1966 a young man from a small town in the middle of Michigan found himself in Vietnam attached to a combat team at a hamlet called Thuong Duc. He had come there, in a way, by accident. Like so many others, he had graduated from college only to find himself facing the draft. Wanting at least some measure of choice over his destiny and not inclined to run, he elected to follow the hardest course of action. duty as a Marine in Vietnam. To wit, he spent large chunks of his free time learning Vietnamese and working at an orphanage in Da Nang run by the Catholic Church.

duty as a Marine in Vietnam. To wit, he spent large chunks of his free time learning Vietnamese and working at an orphanage in Da Nang run by the Catholic Church. In 1971, when he began studying Vietnam veterans’ postwar adjustment issues, Figley said, “I started out just wanting to know what was going on so that I could figure me out better. Then as it dawned on me what the heck was going on, I began to search for the mechanism for the trauma induction reduction process. Once these mechanisms are determined, the rest is easy in designing treatment programs that completely remove the trauma reactivity—not the memory, but the emotional reactions to the memory.

In 1971, when he began studying Vietnam veterans’ postwar adjustment issues, Figley said, “I started out just wanting to know what was going on so that I could figure me out better. Then as it dawned on me what the heck was going on, I began to search for the mechanism for the trauma induction reduction process. Once these mechanisms are determined, the rest is easy in designing treatment programs that completely remove the trauma reactivity—not the memory, but the emotional reactions to the memory. BY MARC LEEPSON

BY MARC LEEPSON