|

|||||||||

|

March/April 2016

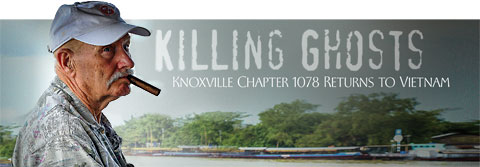

STORY AND PHOTOGRAPHS BY LINDSEY M. BIER

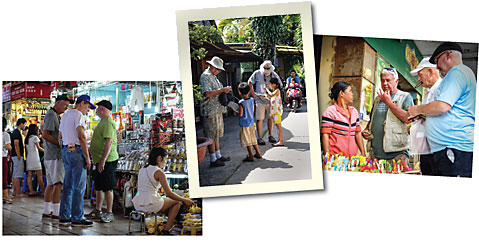

Fourteen members of Knoxville, Tennessee, Chapter 1078 joined together last December as a brotherhood of veterans. Confronting their wartime past, the group embarked on a one-week tour of Saigon and the Mekong Delta region, as well as Hong Kong. The trip fulfilled a longtime goal for chapter member Bill Robinson. Enduring the Hanoi Hilton after his USAF rescue helicopter was shot down, Robinson became the longest-held enlisted POW in U.S. history. But he had yet to step foot below the 17th parallel. “I was finally filling in another square on my bucket list as I was going down life’s highway: to go to South Vietnam,” said Robinson, who gave the keynote speech at the 2015 VVA National Convention. The journey was as much for the cautious as for the eager. Some feared harm, even incarceration, if they dared to return to the land where they once waged war. The strength of the band of brothers with a mission of “killing ghosts” comforted fears, Army veteran and trip organizer Ron Kirby said. Gary Ellis hesitated to go. “I was a platoon leader in combat, and I didn’t know how the Vietnamese would react to me,” he said. Anxieties dissipated for Ellis and others after their plane landed at Tan Son Nhut International Airport. The familiar heat and humidity enveloped the veterans, and the natural beauty of wartime Vietnam shone even more powerfully in peacetime. Most importantly, the Vietnamese were friendly and gracious. “The trip cleared the cobwebs out of our minds,” Army veteran Ricky Graham said. The veterans were amazed by how much had changed since the war. Vietnam has developed from what Navy veteran Don Johnson called “rubble” into a blend of traditional and modern. The veterans saw elderly women wearing conical hats with baskets of fruits in front of a Gucci store and young women in ao dai and high heels zipping around on motorbikes against the backdrop of Saigon skyscrapers.

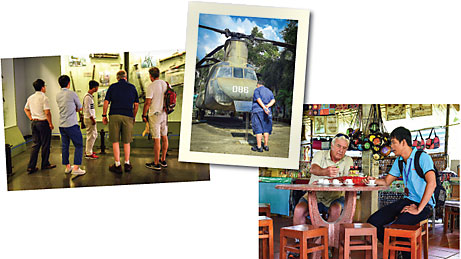

Although the presence of Vietnam’s red flag reminded the veterans that they were in a communist country, the entrepreneurial spirit of the Vietnamese people impressed them. “When you’re in a war zone, you don’t have time to modernize. The Vietnamese have worked hard and come a long way,” said Rob Owensby, an Army veteran who also served in the Marine Corps. In Saigon, Chapter 1078 visited historical sites such as Independence Palace and Ben Thanh Market and cruised the Saigon River. They also explored villages, islands, and canals in the Mekong Delta region. Along the way, they took in traditional musical performances and tasted local delicacies. “The Mekong Delta and the shacks—that’s the Vietnam I remember,” Hurst said. But evidence of war is now far removed from Vietnamese culture. “They’ve put the war in a museum and have gone on with life,” Robinson said. The veterans visited the War Remnants Museum, which tells the Vietnamese government’s narrative of the “American War.” Memories, some bad and some good, surfaced as the men recognized places in photographs. The collection of U.S. tanks and aircraft transported some back to the battlefield. Looking at Hueys conjured memories of jumping into rice paddies and poking fun at comrades whose heads went under swamp water, Owensby said. One exhibit claims that Vietnamese captured thousands of U.S. soldiers but only released around six hundred. The exhibit raised questions about the missing and the need for a full accounting of brothers and sisters, Robinson said. He has friends who are still listed as MIA. “Someday the truth will be learned, but what’s the real truth? We had our propaganda, and they had theirs,” Robinson said. One museum wing reports the multigenerational effects of Agent Orange in Vietnam. “I wish the U.S. government would do more research,” Ellis said. “Our offspring have also been affected.” Disheartened by the museum’s portrayal of Americans, some veterans left quickly. While the realities of war can be horrific, “none of that represented the war that I was in,” Graham said. Everyday Vietnamese, though, don’t treat Americans as bad guys. They spoke freely and expressed appreciation for their wartime help. Kirby said this coming together of Vietnamese and Americans as friends “makes the world a better place.” While learning about the Vietnamese way of life, the veterans discovered Vietnamese are much like themselves: They love their country and fought for what they believed was right. Returning to Vietnam was only part of the healing process. The other part came from veteran-to-veteran understandings: Sharing a war memory brought affirmation from men with similar experiences. Ellis said he wouldn’t have gone on the trip alone without other veterans. There were solitary moments to remember Americans who never returned home. Owensby went alone to an area in the Mekong Delta where he once suffered “48 hours of hell” and lost many friends. “Going to that spot and saying a prayer, that was healing,” he said. But war memories weren’t the only conversations. The veterans joked, talked politics, and shared stories about grandchildren and health issues. They drank 33 beer just as they had more than forty years ago. For some, returning to Vietnam was invigorating. “It makes you dream about when you were young,” Ellis said. “I was a kid and had a lot of energy back then.”

When they landed back in Knoxville, the community greeted them with cheering and flag waving. The message was clear: “Welcome home, heroes.” There were tears, smiles, and hugs. “Until five years ago no one knew I was a veteran because there was a stigma and we veterans always knew that,” Graham said. “It goes back to the reception we received when we returned.” Now more Chapter 1078 members want to exchange painful for pleasant memories. For others, bad memories die hard. Hurst hopes someday to reunite with buddies from his unit and to confront his memories from where he was stationed in Qui Nhon. But, he said, some veterans don’t want to return. “They say, ‘I got out alive once; I’m not going back’.” Those who returned to Vietnam last December have no regrets. Some have noticed direct benefits. After three tours in Vietnam, Owensby suffered nightmares and feared accidentally hurting his wife. Loud noises prompted daytime flashbacks, and he’d reach for where he once carried a rifle on his body. Since returning to the place of his “bad experience,” the nightmares and flashbacks have stopped. Chapter 1078 is planning a similar trip for January 2017, including visiting Da Nang and volunteering at an orphanage. They want to raise funds for members for whom travel costs are prohibitive. “Veterans need to go back and see what’s happened. It’s therapeutic,” Ellis said. “Or they’ll die with a chip on their shoulder.”

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

Endowing the Future |

|||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

|||||||||