|

||||||||||||

|

March/April 2017 Letters

I just finished reading the article about U.S. veterans’ work over the last fifteen years to assist in Vietnam’s efforts to deal with the deadly legacy of unexploded ordnance. It gives me a different perspective on my relief one morning when, on a hill near the DMZ, an NVA mortar round buried itself in the dirt a few feet from me but failed to detonate. I expect that same round is still in the ground waiting to fulfill its deadly mission. But since we practiced fire superiority, most of the unexploded ordnance is ours. Mr. Searcy and the Project RENEW team deserve our thanks and support for their efforts to prevent the legacy of war from becoming the wounds of war. Thanks for The VVA Veteran. I look forward to each issue. Paul Cox

While I’m pleased with what VVA considers a victory (see last issue’s Government Affairs and Agent Orange columns) regarding the peer-reviewed research that undoubtedly will go on for years, three of my four children have learning disorders and my youngest was diagnosed with birth defects. He incurred a more severe learning disorder and vision impairment. And while I am truly happy about this long road ahead, I must remain concerned with my immediate health concerns as well. All of which doesn’t amount to a hill of beans unless you can actually get Congress and the VA to recognize the Blue Water Navy veterans and their life-altering ailments. The VA can’t be the deciding authority on what ships were contaminated and which ones were not. They have never conducted their own studies and won’t accept any others. Just who do they think they are? George J. Durfor

Marc Levy’s “The Quiet Time” in Parting Shot was particularly well written and poignant. Memories of countless morning rituals performed in the Central Highlands were rekindled by his account. And yes, many times a Claymore was sacrificed for its C-4 when the foil-wrapped blue heat tabs were not available. The fumes of those heat tabs were not so pleasant either and would assault your nose and eyes were you so careless to hover over your C-rat can “stove” made with a church key. Mike Rhoades

The essay about GI coffee was right on with one exception: the silliness about losing your foot if you stepped on burning C4. It required a blasting cap or it simply would not go off. Even while it was burning you could stomp on it, hit it with a shovel on a flat rock, run over it with an ACP. No blasting cap, no blast. Period. John Walker

I’m an incarcerated Vietnam veteran in San Quentin State Prison. I have two Honorable Discharges and a General Discharge (Under Honorable Conditions). No stretch of the imagination will ever make me a hero, but I’ll always be a veteran. I’ve been in prison for the last thirty-six years. I hope to be paroled late next year. The only thing prison officials told me about my possible post-prison life was, “Don’t screw up or you’ll be right back here.” When I imagined my life on parole, it wasn’t a pretty picture. My Social Security checks would be small because of all the years I’d spent in prison. All I’d be able to afford would be a good sleeping bag, a set of thermal underwear, and a sturdy pair of boots. Those would keep me fairly warm and dry as I lived in a cardboard box under some bridge or overpass and shared cans of dog food with a stray mutt. A very uncomfortable option, but I couldn’t see any other choice. About ten years ago a couple of my prison friends urged me to attend meetings of the prison’s veterans group. I was reluctant at first, not wanting to be reminded that I’d fallen from a position of some honor and responsibility to being a convicted felon, not trusted for anything. But those guys kept nagging me. Just to get them off my back, I went. To my surprise, almost immediately I experienced a sense of fellowship and camaraderie I hadn’t felt in years. Even more surprising, I learned my military service had earned me benefits like health care and a pension for elderly, impoverished war veterans. They even helped me file a disability claim with the VA. That altered my imagined parole. Now me and the mutt will have a small apartment and an economy sedan. He’ll still get canned dog food, a flea collar, a dog license, and an occasional bath. Me, I’ll upgrade to canned stew and regular baths. I was shocked and thrilled that incarcerated veterans had given me a path to a realistic parole plan with a good chance for a crime-free life and successful community re-entry, while prison staff had just warned me to stay out of trouble. I decided to try doing the same thing for other incarcerated vets. I found an unofficial 67-page training course for a veterans service representative, which was quite helpful. But it also made me painfully aware that the practices, regulations, and programs of the VA are thousands and thousands of pages long. I soon realized that the best thing I could do for my incarcerated peers was to inform them of the benefits their military service entitled them to and quickly add, “You need to talk to a veterans service officer.” But VSOs almost never visit prisons. America’s prisons hold thousands of vets eligible for VA benefits. Accessing those benefits can change their lives and can free some from an ever-worsening cycle of crimes and incarceration that can end in tragedy. VSO visits to prisons can literally save lives and prevent crimes. So why aren’t VSOs going to prisons? James B. Dunbar

In response to Thomas S. Oliver’s letter in the last issue, I draw your attention to the following: “As of January 1, 2000, Section 578 of Public Law 106-65 of the National Defense Authorization Act mandates that the U.S. Armed Forces shall provide the rendering of honors in a military funeral for any eligible veteran if requested by his or her family. As mandated by federal law, an honor guard detail for the burial of an eligible veteran shall consist of no fewer than two members of the Armed Forces. One member of the detail shall be a representative of the parent armed service of the deceased veteran. The honor guard detail will, at a minimum, perform a ceremony that includes the folding and presenting of the flag of the United States to the next of kin and the playing of “Taps,” which will be played by a lone bugler, if available, or by audio recording. Today, there are so few buglers available that the U.S. Armed Forces often cannot provide one. However, federal law allows Reserve and National Guard units to assist with funeral honors duty when necessary. On the day of the burial or interment, the U.S. flag is lowered to half-mast.” This rule does not specifically identify what is commonly referred to as a 21-gun salute at military funerals. The following is offered as additional information on the subject: “One misconception is calling the shots fired at a military funeral a 21-gun salute. Even if there are seven soldiers firing three rounds each, this is not a 21-gun salute, because the soldiers aren’t using guns, they’re using rifles. In the military, guns are considered artillery. Instead, the shots fired during a military funeral are called the firing of three volleys in honor of the fallen. “The firing of three volleys dates back to the custom of ceasing hostilities to remove the dead from the battlefield. Once finished, both sides would fire three volleys to signal that they were ready to resume the battle. “During the firing of three volleys, the rifles are fired three times simultaneously by the honor guard. Any service member who died on active duty, as well as honorably discharged veterans and military retirees, can receive a military funeral, which includes the three volleys, the playing of ‘Taps’ and a United States flag presented to the next of kin. Three spent cases are usually inserted into the folded flag, one representing each volley fired.” I serve with our Chapter Honor Guard, and we have always fired three volleys. Norris Long, President

My thanks to you for the excellent article on military chaplains in the November/ December issue. This honor to our chaplains is timely with the passing of Chaplain Charles Angelo Liteky in San Francisco in January. He was awarded the MOH in 1968 and returned it in 1986—one of only two I believe who have returned the Medal of Honor. If I were to list the top ten people of no relation who have inspired me the most, his name would be the first. John H. Woolwine

There are Vietnam heroes among us. You are the humble warriors who silently blend in like the VC blended into the tropical foliage. You are all unique, but at a young age you were given a ticket by special invitation to an event that no young person should ever have to experience. That important but horrifying venue was the Vietnam War. I was only a child at the time, but I have learned of some of the hardships that you endured, the sacrifices you made, and the injustices that you encountered. We don’t have the luxury of a time machine to right the wrongs. But we can let you know we noncombatants understand your courage and sacrifice for our country and its personal cost to you and your family. Many people like me are dedicating the balance of our lives to thank you for your sacrifice, to honor you, and to show you how important you are to us. We freely offer a helping hand, a listening ear, or words of encouragement to share your story so we can learn. You are a living part of our nation’s history. Along with the names of the fallen on The Wall, the stories you share in books, the letters you share in the VVA magazine, and the campside chats with your grandchildren all guarantee that you will be long remembered. Evelyn Pillinger I read Marsha Four’s article, “True to its Founding Principle.” I’m confused. She seems to dwell on the issue, “Never again will veterans abandon another.” Who abandoned who? She never says. I’ve been around U.S. veterans for almost fifty years, and I don’t recall veterans abandoning veterans either on the battlefield or off. I am a veteran of Panama and Desert Shield/Storm and by your eligibility rules, I feel abandoned by your organization. I am not eligible by the nature of my service but by some dates on a calendar. Do you not see the irony of your position? Am I incorrect or do I detect a feeling of victimization within your organization? Victimization is not a normal trait among U.S. veterans. We are taught to adapt and overcome under all circumstances. It’s almost as if you said that if I can’t play on your playground, I’ll take my toys and go home and pout. This is childish and arrogant. I suspect that your organization does a lot of good for veterans. It’s a shame that by its exclusivity, it has abandoned so many veterans. J.E. Vesely Marsha Four responds: VVA was born from the frustration of being minimized, ridiculed, and disrespected by the leadership of the established veterans service organizations in the 1970s. One glaring example was the huge disparity between the GI Bill of World War II and Korea as compared to the Vietnam-era GI Bill. Our founders took the bull by the horns, adapted, and overcame the hurdles. They united, organized, and fought hard for full recognition as a new congressionally chartered service organization. In that 1986 charter Congress restricted our membership to those who served during the Vietnam War. We are currently reexamining those eligibility restrictions. Thank you for sharing your thoughts.

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

||||||||||||

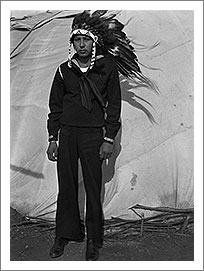

The sprawling, illuminating exhibit of Kiowa photographer Horace Poolaw, For a Love of His People, which documents his friends, family, and neighbors in southwestern Oklahoma, remains on view at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., through June 4. Poolaw served in the U.S. Air Force during the Second World War. The images on display include those of veterans from World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. This is the first public showing of Poolaw’s work since 1990. He died in 1984.

The sprawling, illuminating exhibit of Kiowa photographer Horace Poolaw, For a Love of His People, which documents his friends, family, and neighbors in southwestern Oklahoma, remains on view at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., through June 4. Poolaw served in the U.S. Air Force during the Second World War. The images on display include those of veterans from World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. This is the first public showing of Poolaw’s work since 1990. He died in 1984.