|

|||||||||

|

January/February 2017

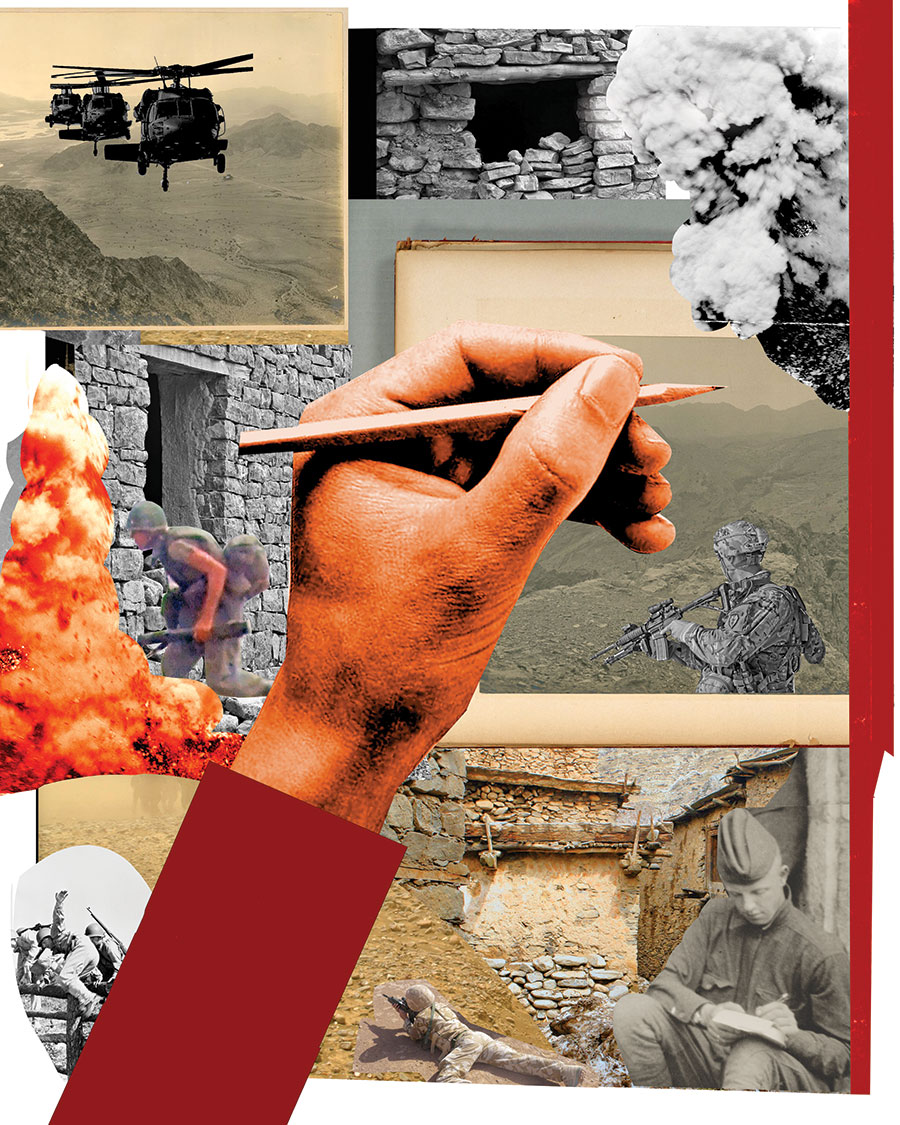

BY RICHARD CURREY Several years ago a community arts center invited me to conduct a writing workshop for veterans. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan had sparked renewed interest in the sacrifices and struggles of veterans, along with fresh attention paid to the notion that participating in creative activities such as drawing, sculpting, and writing might help distressed vets with their recovery and re-entry into life outside a war zone. Some of the workshop participants offered poems or short stories, but most shared memoirs—first-person stories from World War II, Vietnam, Korea, and Iraq. These stories came in different shapes. There were diaries written while serving in combat zones, letters sent home, and recollections penned months—and more often years—after the events they described. Whatever the approach, all were linked by a need to bring a personal truth to the page that conveyed each veteran’s sense of often horrific episodes of loss and bravery, as well as what came next after living through such experiences. Writing, for all of these veterans, felt like therapy. It seemed to many of them that, in some way, writing addressed their emotional pain like nothing else quite managed to do. But can writing personal memoirs actually serve as a tool for addressing PTSD? Most of the men in my writing workshop thought so, but science also supports the idea.

The link between writing and wellness finds its foundation in the seminal research of social psychologist James Pennebaker, who first identified the relationship between “expressive” writing and an improved capacity for dealing with stress-inducing experiences. While Pennebaker did not initially focus on combat-related PTSD, the VA has been interested in the therapeutic potential of writing for some time. Two recent VA studies took another look. In 2013 VA scientists published research on what they called “written exposure therapy.” They noted the need to “identify alternate treatment options for PTSD, especially among veterans where PTSD tends to be more difficult to treat and dropout rates are especially high.” Seven veterans (all men) diagnosed with PTSD enrolled in the study. Four were Vietnam veterans. All seven had been through years of VA treatment that included medications, group therapy, individual counseling, and various recovery programs. Results had been mixed with only modest improvements for most. Over the course of five sessions, each man was asked to write about the initial trauma that incited his PTSD. They wrote for thirty minutes in each session about their trauma—revisiting when it happened, and what happened in the days and months and years that followed. They were asked to bring as much detail as possible to the writing, enlisting memories of sight and sound and smell as well as thoughts and feelings. At a three-month follow-up all but one of the men’s symptoms were significantly improved. In fact, five of the seven participants no longer met medical criteria for PTSD. In 2015 another team of VA and academic researchers looked at writing as a health intervention. They enrolled more than a thousand veterans and split them into three groups. One did no writing. The second wrote factually about information needs of new veterans. The third group was asked to write “expressively” about their transition from military to civilian life and were instructed to “write about their deepest thoughts and feelings”—to work from the soul. When the results were assessed, the researchers noted that “compared with no writing at all, expressive writing was better at reducing PTSD symptoms… for reducing anger, distress, reintegration problems, and physical complaints, and for improving social support.” The factual writing group also saw symptom improvement, suggesting that writing, in and of itself, can bring improvements for veterans dealing with PTSD.

When my writing workshop ended, several students asked if our group might remain informally connected. They did not want to let go of writing as a structured activity—or the support group that had formed. But as it happened, my students would see writing for veterans quickly evolve to become a key resource among the many therapies available to those struggling with PTSD and reintegration issues. One program in particular has gone far in delivering the therapeutic benefits of writing for veterans, the Veterans Writing Project. It provides free seminars and workshops for vets, active-duty service members, and family members. A key aspect of the Project’s mission is investing in the health benefits of writing—what founder Ron Capps calls “the healing power of narrative.” Capps has his own remarkable history, chronicled in his compelling memoir, Seriously Not All Right: Five Wars in Ten Years. Capps tracks his 25-year career from Army enlistment as a private to retirement as a lieutenant colonel, with deployments to Kosovo, Central Africa, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Darfur, even with a stint in the Foreign Service. Capps suffered PTSD so severe that he planned and very nearly managed to take his own life. It took him a long time to “come home,” but in the course of that return he discovered the healing qualities of writing—at first for himself, then realizing how effective this tool could be for any veteran who needed it. Capps earned an M.A. in writing at Johns Hopkins and went on to found the Veterans Writing Project. There are now many other programs that bring therapeutic writing to veterans, including Warrior Writers, the Bay Area Veterans Writing Group, and Syracuse University’s Veterans Writing Group. There is even an online how-to: How to Build Your Own Veteran Writers Group. The federal government also has ramped up the creative therapies that serve active-duty military and veterans. Creative Forces is a partnership between DoD and the National Endowment for the Arts that delivers an array of therapeutic arts, including writing. According to the NEA, Creative Forces “places creative arts therapies at the core of care” in military and veterans medical facilities—and creative writing instructors are a specific part of this mix.

If a veteran still wonders if writing truly serves the healing process, it is useful to look at some memoirs in addition to Capps’s book. Reading how others have told their stories lights a way into how to approach a personal memoir. Colby Buzzell launched his writing as a blog, initially to settle himself and stay centered while serving as an Army machine gunner. His blog led to My War: Killing Time in Iraq. There is Navy doctor Richard Jadick’s scorching account of his Iraq service, On Call in Hell. Vietnam veterans might be particularly interested in former Marine Karl Marlantes’s searching and thoughtful What It Is Like to Go to War. While these few examples can serve to instruct and inspire, tapping the true healing potential in writing is all about telling one’s own story and exploring experiences that, for many, are so devastating they seem to defy any sort of translation. I’m reminded of what my workshop participants told me. One said that he could “write about what he could not speak.” Another said that writing was “pretty damn close to taking a pill for all my anxiety and fear.” Another, a Vietnam vet, told me (only slightly tongue-in-cheek), “I’ve never felt this good about the bad stuff in my life.” Ultimately, finding healing through writing is all a part of coming home. Many Vietnam veterans know this process can take years and massive personal struggle—but writing about it can temper that struggle and help to find meaning. Ron Capps summed it up in the closing lines of his memoir when he wrote, “There will always be wars, but someone else is out there now. Godspeed to them. I’ve done my share. I’m going home.” |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

The Military Working Dog Commemorative Stamp Drive needs your help. |

|||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

|||||||||