|

||||||||||||

|

July/August 2016

BY LOANA HOYLMAN Uplifts and stretching, breaking and melding, the land is never still. In the mountains around Tucson and the Oro Valley there are fossils of sea shells and shark’s teeth, clam shells and camel teeth, dinosaurs and sea monsters. There are volcanoes, metamorphic rocks with rich ore, waterfalls, and shady river systems. And there’s the desert. The Sonoran Desert is so dry it feels as if one’s watery life force is being sucked out. And yet the Coronado Forest just south has a larger, wider biodiversity than even the most lush National Forest. This is Basin and Range country. When the Pacific Plate began to slide under the North American Plate on the western coast, it crunched land all the way into parts of New Mexico and Utah. Land was pushed up into mountains. As the mountains took the area up into vertical peaks, the land between stretched to the breaking point, causing huge basins between the mountain ranges. The result is a series of north-south mountains in cornrows across the land with stretches of basins—sinks with no drains. The valleys were originally far deeper, just as the mountains were far higher. Over the 15 million years since the basin and range turmoil, the mountains have been eroded by wind and water, filling the basins with 5,000 feet of eroded mountain debris. Otherwise, the mountains would be 14,000 feet high and the basins far lower.

Water is king here. In such aridity, it’s hard to grasp that so many desert features are caused by water. There are waterfalls, water holes, creeks, alluvial streams, ponds, and rain both heavy and light. There are floods. Sure, lack of water can kill you, but more people die in deserts of drowning that of dehydration. Flash floods are violent, unexpected, and deadly—filled with boulders, tree trunks, abrasive sand, and heavy silt. Avoid walking in the dry stream beds, called arroyos. Although the sky above may be enamel blue with not a cloud in sight, miles away a heavy thunderstorm you cannot see or sense can dump vast amounts of water. The desert ground is too hard to absorb so much sudden water. It just keeps rioting and picking up more and more debris. When it comes, it sounds like a racing train with no brakes.

There is quieter water here, too, perfect for swimming: rock water holes. There are six around Tucson. All are hike-in. Some are less than half an hour’s walk, while others can take up to three hours to reach. Milagrosa Canyon is one of the best, with three waterfall-fed pools. It takes about an hour to hike in; the best time is from late June through July. Hiking around Tucson has its dangers: cactus needles, flash floods, and sunburn. Check the weather forecast, as clear skies do not preclude flooding. One more thing: Desert soils are often covered with black lichens and mosses that take hundreds—sometimes thousands—of years to establish. This is what keeps the soil from blowing away. One wrong footstep destroys centuries of growth.

Everything is so interconnected that destroying one, destroys many. Mesquite trees, for example, shade the baby saguaros so they don’t roast, but mesquites are in trouble themselves, mostly from cattle. These cacti can grow up to fifty feet tall with many arms, and weigh as much as five tons. The saguaros are threatened on several fronts. Suburbs erupt at the doorsteps of the cactus forests, bringing pollution and too much activity. People steal baby cacti or they vandalize them by carving names into the flesh or knocking off arms. Grazing sheep and cattle have devastated large tracts of saguaros. There are thousands fewer than there were just a couple decades ago. The pollinators of saguaros are bats, which also are in trouble, dying in unthinkable numbers due to exposure to toxic chemicals. You may read that some insects pollinate the giants, but it isn’t true. Only bats do the job.

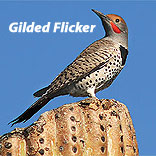

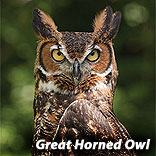

Many birds, including the large gilded flicker, depend on saguaros. With their golden underwings, they’re easy to spot going back and forth from their homes in the big cactus. Hawks use the plants as perches. The elf owl, no bigger than a small sparrow, is nocturnal, but you may spot a little face looking out of its hole in a trunk. Or you may hear one—though you may think it’s a puppy with its yipping sound. The great horned owl lives in the cactus forests, too. Their feathers are shaped and textured to minimize sound as they fly. If you hear one call out, you probably won’t see it. They are ventriloquists, throwing their voices to where they are not. They are big, with a wingspan of about four feet. They can snatch cats, porcupines, and even large ospreys. But the iconic bird of the Southwest is the roadrunner. You’ll see them run and stop, run and stop. They have very long tails and punk haircuts sticking up like crests. They eat things humans don’t like: scorpions, tarantulas, and rattlesnakes. The “X” of their footprint is found in petroglyphs all over the Southwest; they were revered by Indian tribes.

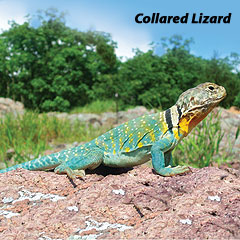

You will see many lizards, despite the diligence of the roadrunner. The male collared lizard is one of the larger ones. His body is turquoise with bright yellow dots, a yellow head, and long, long toes. If you’re really lucky, he will rise up on his hind legs and run. Mule deer roam the desert, each ear as big as its head. Cottontails abound, those surprisingly adaptable bunnies, as well as rock squirrels and poisonous Gila monsters, whose ancestors were around 65 million years ago. There are pig-nosed javalinas, the tiny kit fox, and the gray fox. There are ringtails, elusive and shy, and badgers. Higher up, there are bighorn sheep. There are quail, poorwills, wrens, doves, and cardinals, whose red plumage is shocking against subtle desert colors. Arizona has more than four hundred species of birds, many quite exotic.

And there’s Sabino Canyon. And lush (and cooler) Mount Lemmon. Further from Tucson, the San Pedro River is gorgeous. Kartchner Caverns has limestone caves, and there’s a giant telescope at Kitt Peak. Go early—before 6 a.m.—to avoid the suffocating heat. Take more water than you think you will need. And take hats and sunscreen. But go!

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

||||||||||||

Except during droughts, the rains come between mid-July and mid-September. It is the wet season—the monsoons, they call it. Thunder and lightning storms move across the desert skies with spectacular displays. The storm clouds create sunrises, sunsets, and rainbows that astonish in the clean air of the Southwest. By evening, the storms usually move away, leaving millions of stars across the washed sky. The rains are created by the yearly cycle of warm moisture coming up from the Gulf of Mexico. Warm, wet air meets cool, dry air and creates thunder, rain, and lightning.

Except during droughts, the rains come between mid-July and mid-September. It is the wet season—the monsoons, they call it. Thunder and lightning storms move across the desert skies with spectacular displays. The storm clouds create sunrises, sunsets, and rainbows that astonish in the clean air of the Southwest. By evening, the storms usually move away, leaving millions of stars across the washed sky. The rains are created by the yearly cycle of warm moisture coming up from the Gulf of Mexico. Warm, wet air meets cool, dry air and creates thunder, rain, and lightning.

DESERT DENIZENS

DESERT DENIZENS The vast Coronado National Forest lies south of Tucson. Catalina State Park—just minutes north of the El Conquistador—has a mesquite bosque, saguaros, and mountains. Two saguaro forests flank Tucson. The Saguaro National Forest West is closer and bigger, and offers a vast, glittering night sky and dramatic overlooks. The eastern forest is more intimate and includes a paved, accessible trail.

The vast Coronado National Forest lies south of Tucson. Catalina State Park—just minutes north of the El Conquistador—has a mesquite bosque, saguaros, and mountains. Two saguaro forests flank Tucson. The Saguaro National Forest West is closer and bigger, and offers a vast, glittering night sky and dramatic overlooks. The eastern forest is more intimate and includes a paved, accessible trail.