|

||||||||||||

|

January/February 2016

BY RICHARD CURREY

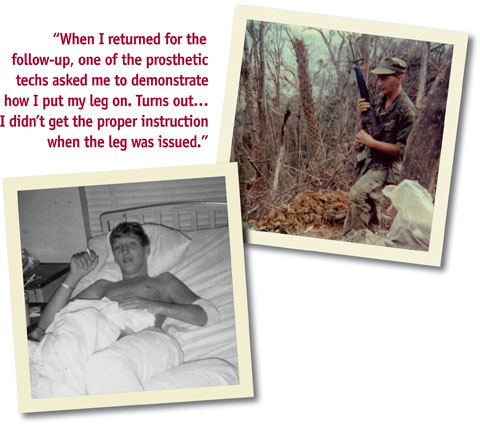

He quickly learned there were no other amputees at St. Albans. “There were paraplegics,” he said, “guys with head injuries, burns. But I was the only amputee. I had nobody to talk to who was going through what I was. No camaraderie. No bonding. I felt very alone.” Compounding his sense of isolation, Foote’s medical recovery was rocky. “I kept developing infections and the surgeons kept cutting. When my doctor told me they would have to take it above the knee, that really knocked me back. I imagined myself in a wheelchair for the rest of my life. I was deeply depressed.” But when a burn victim died—a man who always happily greeted Foote despite devastating injuries—something changed in Ned Foote. “This guy was upbeat no matter what. And suddenly he’s gone. That could’ve plunged me deeper into depression, but somehow it took me the other way. I realized I wasn’t alone—a lot of guys had it rough. I decided to quit feeling sorry for myself and do what was necessary to get back to my life.” Foote’s first prosthetic leg was issued at the VA hospital in Albany, New York—with virtually no instruction for its use. “It was just sort of handed to me.” Foote went home and put the leg on based on the cursory instruction he’d heard only once. “When I returned for the follow-up, one of the prosthetic techs, a man named Bill Sampson, asked me to demonstrate how I put my leg on. Turns out I wasn’t getting it right because I didn’t get the proper instruction when the leg was issued. Bill worked with me until I got it down.” It was a life-changing meeting. Sampson owned an independent prosthetics company that contracted with the VA, and he brought a patient-centered approach to his work that the VA did not offer. “Not the VA of 1970, anyway,” Foote said. He worked with Sampson and later with his son, Bill, Jr., who took over the company after the elder Sampson retired. Bill Sampson, Jr., has been Foote’s prosthetist for forty years. “Without Bill, I wouldn’t be wearing the leg I’ve got on today,” Foote said. “He’s fought for me all the way.” The first computer-controlled prosthetic leg, the “C-Leg,” became available in 1999. Sampson was one of the first prosthetists in the nation certified to fit it. Ned Foote became one of the first amputee vets to receive a C-Leg through the VA. “But not without a fight. The VA said the C-Leg was too expensive. They claimed its benefits were exaggerated.” Rick Weidman, VVA’s Executive Director for Government Affairs, took Foote’s case to Fred Downs, also a Vietnam veteran amputee who was then director of the VA Prosthetic and Sensory Aids Service. Downs approved the initial purchase. Bill Sampson handled the fitting. “Needless to say,” Foote said, “the C-Leg was way ahead of the old technology.” The next prosthetic breakthrough, the Genium leg, came along in 2011 and marked another VA battle for Foote and Sampson. They fought the requisite mountain of red tape and again finally prevailed. Foote now wears the Genium, which he said “mimics your nervous system. A computer chip receives impulses from the foot to help control stride and balance.”

Despite his battles with the VA, Ned Foote remains positive about the institution. “The VA is far better today than it was in 1970,” he said. “Overall, I’ve received great care through the years. But there is still too much of the old thinking—cutting costs at the expense of veterans. We all know it’s wrong to ask young people to sacrifice so much and then not deliver the best care and rehabilitation when they come home. But it still happens.” Foote, recalling his visit to Walter Reed’s gleaming Amputee Service with its large bright rooms filled with physical therapy equipment, said that “it’s great to see what’s available to our young vets. It’s as it should be. But at the same time I can’t help but feel a bit of sadness and disappointment that Vietnam amputees got so little and had to fight so hard to even get that. My own story is just one small piece of it, but it’s all there—the limited options, battles for care, delays, excuses. “I still have to wonder why it was we could put a man on the moon but we couldn’t develop better prosthetics for the guys who lost limbs in Vietnam.” Foote acknowledged that much of that problem goes back to deeper issues the Vietnam War generation faced. “The war was so unpopular that the country simply would not pay attention. We all know what happened—the vets who fought this war saw their problems overlooked, swept under the rug. And that certainly included the amputees.”

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

||||||||||||

On a Marine Corps operation in the DMZ in April 1969, VVA New York State Council President Ned Foote was third man back in a point team hit by Claymore blasts that “took out nine of us—two killed, seven injured.” Foote lost his lower left leg and was medevaced to the U.S.S. Sanctuary to undergo the first of many surgeries. After a stop in Guam for more surgery, Foote went on to the St. Albans Naval Hospital on Long Island.

On a Marine Corps operation in the DMZ in April 1969, VVA New York State Council President Ned Foote was third man back in a point team hit by Claymore blasts that “took out nine of us—two killed, seven injured.” Foote lost his lower left leg and was medevaced to the U.S.S. Sanctuary to undergo the first of many surgeries. After a stop in Guam for more surgery, Foote went on to the St. Albans Naval Hospital on Long Island.