|

||||||||||||

|

January/February 2016

BY WILLIAM C. TRIPLETT The Military Advanced Training Center at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, looks a lot like any other gym. There’s the usual array of exercise equipment and machines, even a rock-climbing wall. At any hour of the day you’ll likely see men and women lifting weights, working out, testing themselves, and pushing hard toward a goal. But the people here aren’t ordinary gym members. And the goals aren’t a simple matter of shedding a few pounds or toning up for the beach. Everyone is missing at least one body part, often more. Hands, feet, arms, and legs—limbs lost to war or some other terrible misfortune—have been replaced to varying degrees by prosthetic devices. The men and women using the MATC (“mat-see,” as everyone calls it) are working toward feeling whole again by relearning what most of us don’t even think about, things like how to walk or pick up a cup of coffee. That’s just the beginning, though. The vast majority are looking not only to adapt to their newly imposed limitations, but to embrace them—and eventually to go beyond them. Former MATC patients have become paralympians. Others have run marathons and climbed Mt. Kilimanjaro. One double-amputee is now a professional race car driver. “One of the hallmarks of this place is we have a lot of young, motivated, and competitive people,” said Joe Butkus, a MATC occupational therapist. “That’s a big part of their personality, and it’s usually why they got into the military.” Implicitly and explicitly, the guiding philosophy is that a limitation doesn’t have to be a limitation at all when it comes to leading a rewarding, fulfilling life. As the MATC website puts it: “A major goal of the MATC is to enable the servicemembers to make their own choices and not let their futures be dictated by the injuries sustained.” Achieving that goal requires a unique facility and a dedicated staff with a constellation of expertise—one patient’s care team can include as many as thirty to forty doctors, nurses, clinicians, and therapists. But as Butkus noted, the inspiring successes of the men and women who come through the MATC have a lot to do with their own character. Indeed, another MATC therapist thinks that the determination of patients to resume normal and robust lives has driven prosthetic and rehabilitation technology to higher levels.

“About two weeks after they have surgery and their stitches are healing is typically when they come here,” said Dave Beachler, a prosthesis technology specialist. “Immediately we start fitting them with a prosthesis, whether it be an interface liner which protects their limb from a hard socket, and then also casting to begin the process of making the prosthesis itself.” Everything from design and fitting to milling and production is done on premises. Some components, such as a hand or a foot, are available on the commercial market, but the OPS has a 3D printer, which can produce components in exacting detail. That can be crucial, as each injury is different, even those that involve the same limb. For instance, a leg amputated above the knee presents different prosthetic issues than a leg amputated below the knee.

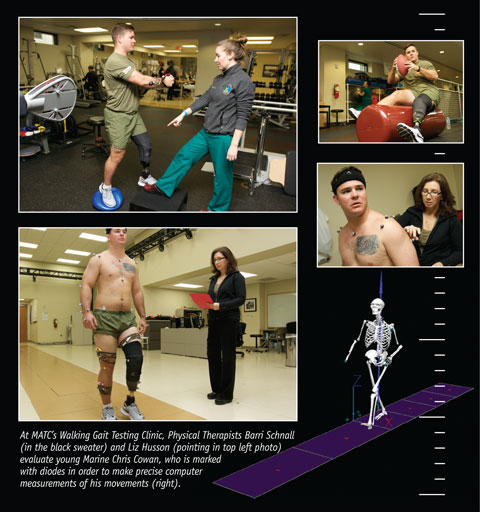

How long the overall fitting process takes depends upon the extent of the injury or injuries. “We have a lot of complex cases with multiple implications—quadrilateral amputees, triples, bilaterals,” Beachler said. “It could take a number of days, maybe just a week, if they’re a simple, below-the-knee amputee. Longer for more complex injuries.” The objective is to get patients fitted and moving again as quickly as possible. When Beachler started working in MATC’s OPS in 2006, he was mostly seeing single-amputations resulting from injuries sustained in Iraq or Afghanistan. But as U.S. military personnel began to expand foot patrols in those two theaters, “we began to see more bilaterals and triples, mostly IED-related,” he said. “It was a busy place then, and it’s still a busy place.” Not all injuries are from combat. Active as well as retired service members and their families can be treated at the MATC regardless of the cause of injury. For instance, Chris Cowan is a young Marine infantryman who lost his left leg above the knee after a motorcycle accident in North Carolina last year. In September he was fitted for and received his prosthetic within two days. Helping Cowan and others adapt to their new limbs is the focus of the MATC’s occupational and physical therapists. But it’s not just a matter of addressing the visible injuries. “People sometimes have PTSD or shattered ear drums, injuries you can’t see,” said Robert Bahr, a MATC physical therapist for the last twelve years. “All these things can have an impact on your ability to rehabilitate them. So you first go through a comprehensive evaluation of the person and make sure you’re going to be hitting all the main things they need.” Then there are different types of prostheses. Some have microprocessors tuned into muscle contractions. And some can detect muscle contractions of a specific type—such as for opening or closing a hand, even rotating it at the wrist. “There are prosthetic limbs now that can pick up a grape and put it in your mouth without squashing the grape,” Bahr said. “But it’s all a matter of learning how to make the limbs work properly for you.” It can take time. “It was weird,” Cowan said of the first time he worked with his new leg. “I thought it’d be just like walking on two legs again, but it wasn’t. It took a lot of getting used to.”

Butkus says he and his colleagues in occupational therapy rely on what they call a “prosthesis thesis,” which is a way of pairing certain exercises or training with the patient’s personal interests or ambitions. “You kind of guide them along with something that’s meaningful to them.”

Many young patients want to participate in sports. The MATC’s holistic approach makes that possible. “We have a number of recreational therapists here that help get people get involved in golf, adaptive skiing, adaptive water sports, even biking and other things,” Butkus said. But physical therapists are very much involved, too. As Bahr said: “We have a sports model we use here to rehabilitate people by strengthening their core and working on their cardiovascular endurance and also working their residual limbs.” Certain muscles have to be built up to compensate for the loss of others. “For a leg amputee, the shorter their limb length is, the more effort it requires to mobilize on the leg.” Steve Peth is a Vietnam veteran and one of about seventy-five Red Cross volunteers at MATC. His main job is to offer support in any way he can. He remembers a Marine who’d lost both legs above the knee to an IED and who wanted to build up his core. “He needed someone to hold his residual legs so he could do lots of sit-ups,” Peth said. “That’s what I did, hanging onto his legs.” Cowan’s initial rounds of physical therapy involved building up his quad muscles before trying to walk on his new leg. Once he got the prosthetic on, he hit the walking bars—which look like a set of parallel bars—but instead of doing twirls and handstands, he was trying to move without falling. “The balance came pretty quickly,” he said. “But it was still like walking on stilts.” It’s not uncommon for patients to need socket adjustments as a result of either exercise or weight change. Here again the MATC stands out. All adjustments—even replacements, if necessary—can be done immediately since everything is located here. “Elsewhere,” Butkus said, “it’s a lot of back and forth because different departments and services are in different locations.” Cowan, for instance, has had several socket adjustments and is now on his fourth foot. But he definitely feels MATC has him on the right track. As part of recreational therapy, last December he and several other patients were able to go to Colorado, where he learned how to snowboard. A self-described “Alabama boy,” he says it’s now his favorite sport and he looks forward to getting better at it. Some MATC alums have distinguished themselves in sports. Bahr remembers working with the first female servicemember injured in the Iraq War—an Army lieutenant leading a convoy when a roadside bomb exploded and took her left leg. She eventually qualified for the U.S. Paralympics Team and competed in the 2008 games in Beijing, coming in fourth place. For the closing ceremonies, she was the U.S. flag bearer. Peth is still in touch with a former Marine who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. In Iraq, an IED sprayed him with shrapnel; but in Afghanistan, another one took his left leg above the knee and mangled his other limbs pretty seriously. One day in the MATC he and Peth discovered they shared a deep interest in auto racing. A lot of therapy ensued that helped the Marine achieve his goal of becoming a professional racer in a car with modified controls.

Bahr has worked in physical therapy for forty years. When he started, prosthetics were all made of wood—nothing at all like the sophisticated ones of today made of titanium or carbon with digital technology embedded. In the civilian rehab programs where he previously worked, the patients tended to be older men and women. Their mobility didn’t involve much more than going from room to room at home.

In Vietnam, Peth said, “We were able to save a lot of lives because of the speed we could extract the wounded and get them to a medical facility. That speed hasn’t changed much. But there’s been a dramatic change in survival rates now because of the medicine. The medicine is dramatically different.” Nonetheless, these young men and women are human, subject to the gamut of emotions that can overwhelm anyone dealing with a personal tragedy such as the loss of one or more limbs. It can be especially difficult on servicemen and women. “With military guys, a lot of it is about your physical performance,” Butkus said. “When that’s the most important thing and it changes, it’s really difficult to find other things people see value in. It’s a fundamental change.” “A lot of physical therapists work one-on-one with patients. They work every day usually at same time, they know them, and they can tell if the patient’s having a bad day, is struggling,” Mark Oswell, a Walter Reed public affairs officer, said. “Some patients you have to push, others you pull, others you have to leave alone.” “Sometimes people don’t want to take the initiative,” Butkus added. Patients will occasionally want to tough it out, acting as if they don’t really have a problem. That’s especially the case, Butkus said, “when they see someone else who has a lot more injuries, and they see that person feeling better than they are, then they don’t want to complain about their own problems, which is really counterproductive. Because everyone is dealing with their own situation regardless of how severe an injury is.” Sometimes the opposite can happen—patients arrive uninspired, unmotivated, and after seeing others in similar condition or worse, become absolutely determined to recover. “When the accident happened,” Chris Cowan said, “I thought my life as I knew it was over. I’d always been active. But then I got here and met Flip”—another patient who is a triple amputee with major damage to his one remaining hand. “He was doing push-ups when I came in. If that doesn’t motivate you, I don’t know what will. It definitely lifted my spirits.” Another unique boon Cowan felt was the comradery of the MATC—specifically, the military comradery. “I thought I’d lost that leaving my unit,” he said. “But when meeting others here, I really felt it. We all talk the same, tell the same jokes.” There’s definitely some inside humor among MATC patients: Above-the-knee amputees say below-the-knee amputees just have a paper cut.

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

||||||||||||

Adjacent to the MATC main space is the Orthotics and Prosthetics Service, which makes custom-fitted prosthetics for each patient. Workbenches with tool boxes fill the room. The OPS is the first step in the rehab process.

Adjacent to the MATC main space is the Orthotics and Prosthetics Service, which makes custom-fitted prosthetics for each patient. Workbenches with tool boxes fill the room. The OPS is the first step in the rehab process. Then there’s heterotopic ossification, a bony growth on the residual limb that sometimes looks like tree roots. “They can be really painful,” Beachler said. “So we have to make sure we’re customizing their socket-fit so there’s no discomfort.” Heterotopic ossification can vary from patient to patient, so individual adjustments have to be made and refined. “Once we have that cast, we make a check socket, which is made out of clear plastic, fit that onto their residual limb, and we can heat that and push out certain areas that might be uncomfortable for them.”

Then there’s heterotopic ossification, a bony growth on the residual limb that sometimes looks like tree roots. “They can be really painful,” Beachler said. “So we have to make sure we’re customizing their socket-fit so there’s no discomfort.” Heterotopic ossification can vary from patient to patient, so individual adjustments have to be made and refined. “Once we have that cast, we make a check socket, which is made out of clear plastic, fit that onto their residual limb, and we can heat that and push out certain areas that might be uncomfortable for them.” For example, he remembers working with a Marine who needed to learn how to adjust to his prosthetic arm. “He was interested in going to architecture school, so we talked about different things, and he said he liked doing models and designs. He found a design of a house online and started to adapt it for a model. It was all self-directed, and he realized after he started making the model, one of the rooflines wasn’t up to code. So he removed the roof and did it all over. I don’t think he had any idea how long the whole thing was going to take, but it was hours and hours and hours.” The Marine now is taking classes in architecture, and the minutely detailed model sits on a high shelf just off the MATC.

For example, he remembers working with a Marine who needed to learn how to adjust to his prosthetic arm. “He was interested in going to architecture school, so we talked about different things, and he said he liked doing models and designs. He found a design of a house online and started to adapt it for a model. It was all self-directed, and he realized after he started making the model, one of the rooflines wasn’t up to code. So he removed the roof and did it all over. I don’t think he had any idea how long the whole thing was going to take, but it was hours and hours and hours.” The Marine now is taking classes in architecture, and the minutely detailed model sits on a high shelf just off the MATC. But at MATC, he said, it’s very different: “We have a group of individuals who all come from that same military discipline of getting the job done, They consider rehabilitation their job now.” Hence, their high degree of motivation. But age also factors in. “Working with a group of young people who are amputees is a lot different from working with older people. Young people have different expectations of their prosthetics. I think the technology has been pushed forward because of the requirements of the younger soldier. The rehabilitation equipment, they’ve had to upgrade it, and they’ve had to make prosthetics last longer. These people have long lives ahead of them, and they may have small children to run after, families to raise.”

But at MATC, he said, it’s very different: “We have a group of individuals who all come from that same military discipline of getting the job done, They consider rehabilitation their job now.” Hence, their high degree of motivation. But age also factors in. “Working with a group of young people who are amputees is a lot different from working with older people. Young people have different expectations of their prosthetics. I think the technology has been pushed forward because of the requirements of the younger soldier. The rehabilitation equipment, they’ve had to upgrade it, and they’ve had to make prosthetics last longer. These people have long lives ahead of them, and they may have small children to run after, families to raise.”