|

|||||||||

|

Books in Review, March/April 2016 We Gotta Get Out of This Place: REVIEWS BY DAVID WILLSON AND MARC LEEPSON

Back home in Seattle at the time, I was mired in a job I hated and in a relationship that was driving me nuts. That song resonated with me in a strong way. When I got my draft notice late that year, I had mixed feelings, but one of them was that I’d been handed an honorable way to get out of this place—Seattle. And I did, in January 1966. Twenty months later I was preparing to leave Vietnam. Music had helped me deal with my time there. I had a small record player and a dozen LPs that I listened to over and over: The Beatles, Elvis, The Lovin’ Spoonful, Judy Collins, and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band were my favorites. The radio helped, too: Merle Haggard’s “I’m a Lonesome Fugitive” was the song I looked forward to hearing the most. Which brings us to We Gotta Get Out of This Place: The Soundtrack of the Vietnam War (University of Massachusetts Press, 256 pp., $26.95, paper). Authors Doug Bradley and Craig Werner have given us a gift: a compendious book that looks at the music we rock-and-roll-generation Americans who served in the Vietnam War listened to. Bradley, a Vietnam veteran, teaches a course called “The U.S. in Vietnam: Music, Media and Mayhem” with co-author Craig Werner, a professor of Afro-American Studies, at the University of Wisconsin. Bradley served as an information specialist at USARV headquarters near Saigon. He’s the author of a fine book of short stories about life in the rear during the Vietnam War called DEROS: Dispatches from the Air-Conditioned Jungle. Werner and Bradley conducted more than two hundred interviews for the aptly titled We Gotta Get Out of This Place. The thing that surprised me most is that I kept encountering the names of old friends in the book. My positive feelings about this book were amped considerably when I got to read extended pieces by the Vietnam veteran poets Bill Ehrhart, Gerald McCarthy, and Horace Coleman. Werner and Bradley did a superlative job rounding up the best people to interview. They include a good number of what the authors call “solos,” extended first-person testimony from Vietnam veterans. VVA founder Bobby Muller does one solo, in which he relates the tale of how Bruce Springsteen single-handedly saved the organization from going under in 1981 (See feature). In five fascinating chapters, the authors cover virtually every possible aspect of music and the Vietnam War. No turn is left un-stoned, you could say. That is to say, the relationship between drugs and music is a big part of the book. I’m often asked about drugs and about the lottery system. I served in Vietnam in 1966-67 at USARV headquarters so my Vietnam War involved no drug use or observation of drug use. And the lottery happened years after I was out of uniform for life. No amount of explanation of either of those things convinces anyone. This is the book people with those questions should read. Bradley and Werner do a great job with Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler’s “The Ballad of the Green Berets,” a complex and interesting story. It was released as a single on January 11, 1966, just as I was starting basic training at Fort Ord, California. We had radios that we kept on whenever we could get away with it. It seemed the song played constantly. Leroy Bearmedicine, a member of the Blackfeet Indian Nation in Montana, a gifted singer and guitarist, led evening sing-alongs featuring “The Ballad of the Green Berets,” which he sang very tongue in cheek. That’s my happiest memory of Basic, all of us booming out the words, “jump and die.” We also sang parodies which Bradley and Werner fully explore. The authors also do a great job with the Animals’ version of “We Gotta Get Out of This Place.” It’s a rare Vietnam War novel or memoir (and I’ve read hundreds) that doesn’t at least mention this song by Cynthia Weil and Barry Mann. They wrote it for the Righteous Brothers, but the Animals made it their own without consulting the composers. There’s a wonderful memory about singing the song from Ann Kelsey, who served as a nurse at the 12th Tactical Fighter Wing Hospital at Cam Ranh Bay. For anyone who wants to know about music and the Vietnam War, this is the book to read. Will another book ever be needed? I can’t imagine it. This is the book that I’ve long wanted on this subject. If I were still teaching a course on the Vietnam War, I would use this book as a text. D.W.

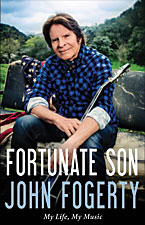

John Fogerty, the leader of the band, was born in May of 1945, which put him in line for military service during the war. In 1966, he was classified 4-F for the draft. As he writes in his new autobiography, Fortunate Son: My Life, My Music (Little, Brown, 405 pp., $30), written with Jimmy McDonough: “Most of us felt that if you got drafted, you were going to Vietnam. And if you went, you were probably going to die.” So, Fogerty says, he was smiling when he received his 4-F classification in 1966. That smile disappeared when his California draft board reclassified him 1-A and sent him a draft notice. He was in the band that would become Creedence, married with a baby on the way, and working in a gas station. With his wife Martha’s help (she pleaded with an Army Reserve sergeant), he joined the Reserves. Fogerty had Basic Training (which he refers to as “active-duty boot camp”) and began attending his monthly weekend Reserve meetings. But when it was time for summer camp in 1967, Fogerty had had it with the Reserves. He wanted to grow his hair long. He wanted to go to meetings during the week rather than on the weekends. So Fogerty decided “to resist, go against the grain. And try to get myself removed from the reserve.” He began fasting. He wrote to his congressman. He saw a lawyer. He took an unused syringe to summer camp, hoping it would be discovered and he’d be discharged. After getting his weight down to 129 pounds, he was diagnosed with “a mild form of dysentery.” That did it; John Fogerty received his discharge in the summer of 1968. The next year Creedence was the hottest band in the country. By that time John Fogerty had turned vehemently against the war, but not against his contemporaries who took part in it. As “a guy in a rock and roll band who was exactly the same age as those soldiers, I tried to represent the cause as best I knew how,” he says. “It would just bring me to my knees, it was so sad and very real to me. I must admit that practically every time I’d think about the guys, our vets, I would cry. I would hear ‘Where Have All the Flowers Gone’ on the radio and would lose it. Because it was just so senseless.” Those in Vietnam, he writes, “were pretty much just thrown out there on their own to improvise. Hopeless. I still feel sorrowful about those times.” The bulk of this breezily written book deals with Fogerty and Creedence’s ups and downs (there were plenty of both) in the sixties and seventies. Fogerty broke a long self-imposed embargo of performing his sixties hits at the July 4, 1987, Welcome Home concert HBO put on for Vietnam veterans in Washington, D.C. He did the old ones because, he says, he “owed the vets. I wanted to be deferential to them, in the hope they’d understand that I personally recognized what they’d done for us. The most special thing I could think of was to do my old songs from the Creedence era. Just for the vets.” Fogerty and his band launched into “Born on the Bayou,” and the “roof came off the place. I’m not even sure what happened for the next forty-five minutes. I just know it was a good thing.” It’s a good thing John Fogerty has set down his musical life and times in this book. And it’s a good thing he has not forgotten the men and women who served in the military during the Vietnam War. M.L.

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

Endowing the Future |

|||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

|||||||||