|

|||||||||

|

July/August 2013

Great Strides: The Partnership Between VVA And The BY MARC McCABE Some three years ago VVA’s Florida State Council undertook an effort to help the veterans of the Seminole Tribe of Florida and their families. Who are these veterans? They have fought in every war in which Americans have been involved—sometimes with, sometimes against. In Vietnam they fought valiantly and participated in major battles, from the Ia Drang Valley to Khe Sanh to Dak To. The Seminoles have a long warrior tradition—a tradition that extends to the current wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Seminole people are descendants of the Creeks. The diversity of the tribe is reflected in the fact that its members spoke seven languages—Muscogee, Hitchiti, Koasati, Alabama, Natchez, Yuchi, and Shawnee. The early history of the Creek people in Florida is not well understood. The Apalachee were a Hitchiti-speaking people who may have been related to the Creek, Tamathli, or Apalachicola. The Apalachee, who lived along the Apalachicola River in the Florida Panhandle, were already in Florida at the time of Spanish contact. At the beginning of the sixteenth century the Spanish attempted to set up a system of missions across northern Florida and southern Georgia. While these efforts failed in Creek country, some Creeks were drawn from Georgia down to the Spanish missions in Florida. Around 1760 the first Creek-speaking people settled at Chocuchattee (Red House) near present day Brooksville, Florida. Drawn together by clans of early Creeks, they became the Seminole Indians. They were cattlemen. Soon the vast cattle herds of the growing Seminole Nation drew the attention of their white neighbors to the north. The conflicts occurring in Georgia began to spill into Florida due to an increased white hunger for land and cattle.

These dates can be misleading. Some historians claim that the destruction of the British post on the Apalachicola River was the last battle of the War of 1812, while others call it the first battle of the First Seminole War. It is unlikely that anyone at the time saw the difference. In reality, all of these conflicts added up to one long, half-century war against the Creeks. By 1823 the Seminole population had increased three or four fold with the arrival of newcomers—small bands of Creeks and Seminoles who became cattle farmers. This population of about five thousand was thrown together and subjected to the Second Seminole War, the fiercest ever waged by the U.S. Government against native peoples. By the end of the war there were only three hundred Seminoles left in the territory. Then, during the Third Seminole War, another 240 or so Seminoles died. In the protracted conflict nearly the entire Seminole population—men, women, and children—was slaughtered.

As VVA chief service officer, my office is located at the VA Regional Office in St. Petersburg, Florida—some 165 miles from the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Brighton Reservation, which includes the Veterans Building for tribal members who served in the armed services. I have made this trek for close to three years; it’s a trip of some six and a half hours—not counting the seven hours spent working with veterans. The initial trips were physically, intellectually, and emotionally exhausting. My first visits also were very intimidating. I knew very little about Seminole culture or about the veterans themselves. They had an enormous mistrust of the U.S. Government and of the VA in particular. I continued to make trips to the reservation at Brighton to help veterans with their claims, but those early days were full of uncertainty and mistrust. Once a month I left my house at 4:30 a.m. to arrive at the reservation by 9 a.m. For the first several months I questioned why I made the trips, as it was clear I was perceived as an outsider and an ignorant interloper. In order to help these veterans (at first only Vietnam-era veterans), I knew I had to do my homework, so I went to the Florida State University libraries. I quickly learned why these warriors were both proud but apprehensive. It took nearly ten months to break the ice. Now there is very good communication among us veterans. We trust each other, and together we have enjoyed many successes. I am proud of the cooperation between VVA and the Seminole Tribe of Florida. Often the closure is as significant as the financial windfall. One success story developed from the plight of a Seminole veteran who was attempting to get his claim before the Veterans Benefits Administration for type 2 diabetes and ischemic heart disease. Joe Lester John had served in Vietnam with the U.S. Air Force as a survival team leader for air crew members. His claim recently had been denied as had those of many other tribal members before him. We researched and developed his claim, then asked for a reconsideration based on new and material evidence. During this process, Joe Lester John asked me pointed questions about a subject that I knew was difficult for him to broach. His daughter was born with a birth defect that he felt he had caused. She was a victim of his exposure to Agent Orange and had been diagnosed with spina bifida at birth. When I explained that this is a compensable illness, Joe Lester John was leery because he already had been denied this benefit. But by this point I had been accepted and the veterans treated me as one of their own, something that brings me great pride and satisfaction. When I asked John to trust me and develop the case again, his family once again was plunged into a whirl of anguish about John’s 32-year-old daughter. We compiled the paperwork. Then, because she had already been denied, I traveled to the Regional Office in Denver to argue that this was a clear and unmistakable error by the VBA. Armed with abundant evidence, I was able to present the case to the assistant service center case manager for children of Vietnam veterans. Just prior to the decision, Joe Lester John died. Two weeks later, while his daughter was going through yet another surgery, I received a phone call from Denver explaining that, yes, the original determination was in error and the grant of level III spina bifida would be retroactive to 2010. This case opened the gates not only to Seminole veterans of all eras but also to the veterans who are employed by the Seminole Tribe of Florida. We filed a notice of disagreement on the date of benefits. While we are pleased to get the grant, we feel it should be retroactive to the date that a claim for this helpless child was filed in 2000. The Seminole Tribe of Florida’s Health Plan will be reimbursed some $1.34 million for the care they provided the daughter of this Vietnam veteran.

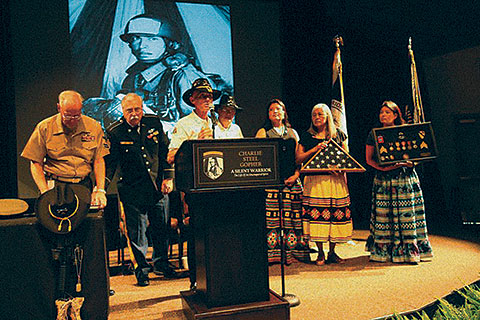

I didn’t know Gopher, but I knew and served with people who could have been his twin. We all served in our own little hell in the Republic of Vietnam. We are the faces and survivors of those horrific moments in life, the battles for Hoa Hoi, Khe Sanh, Hill 881, Kim Son, and many others whose strange names live forever in our psyches. Charlie Steel Gopher was a Native American fighting for his country with the 1st Cavalry Division. However, he also fought the demons that came with those battles, compounded by the mixture of alcohol and race relations prevalent in the military during the ’60s. Almost thirty-seven years ago Gopher took his life. The demons of war and the disrespect of his government that sent him to that faraway jungle to fight in an unpopular war finally got the best of him. That, however, wasn’t the only loss that day: Charlie Steel Gopher was abandoned by his government once again when his family applied for burial benefits. The Veterans Administration (today the Department of Veterans Affairs) denied his family’s request and said Gopher was a dishonorable veteran who rated no benefits from his country. His family did what most did in the ’70s: They accepted it and moved on. They buried him. Gopher’s legacy was left to be discovered by his daughter, Rita McCabe. The story really began in 1965 in the Ia Drang Valley. Charlie Steel Gopher had enlisted in the Army and decided he wanted to join the Army’s elite Airborne. He enlisted for a three-year tour of duty. He went to Vietnam and served with valor in two of the fiercest battles of the war. Gopher continued to serve with distinction, completed his tour in Vietnam, and returned home. The Army asked that he immediately be discharged so he could re-enlist for six more years. This is where Gopher’s tale gets lost and the government betrayed his honorable service. The VA decided that because Gopher did not serve out his original enlistment of three years he should not have the honors of a military funeral. They took it one step further and said Gopher’s service was dishonorable. While it is true that his second tour was considered other than honorable, it was not dishonorable. But Gopher had no one to speak for him in 1975. The VA should have honored Charlie S. Gopher with a full military funeral and a flag for his casket, a headstone, and an honor guard. Now, after a request to reopen his case, the VA finally has granted his family the honors Gopher so rightfully deserved thirty-seven years ago. Last Veterans Day, after we won this case before the VBA, the Seminole Tribe of Florida once again celebrated the life of this brave warrior. The brigade commander from the 1st Battalion of the 12th Cavalry of the 1st Cavalry Air Mobile presented the family and the tribal veterans the awards and honors Gopher never received during his brief life. These and similar stories will be told for some time to come as the Seminole Tribe of Florida continues to see the toll of wars in far-off countries. Presently, young Seminoles serve in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other areas of conflict with valor, distinction, and honor. With the help of VVA’s Florida State Council, the Veterans Council of the Seminole Tribe of Florida, and the Americans Serving Veterans Foundation, we have enrolled all veterans and the employees of the Seminole Tribe of Florida in the VBA system. To date we have recovered more than $5 million (not including the $1.34-million spina bifida award) for our Seminole brothers and sisters who fought in Vietnam. VVA Welcomes Home all Seminole tribal veterans of Florida. A strong and vibrant partnership has developed between VVA and Florida’s Seminole Tribe. Great strides have been made in outreach.

|

|||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

|||||||||

During the early 1800s the Seminole population in Florida remained fairly small—around 1,200—compared to the main body of Creeks in Georgia and Alabama, who numbered possibly 25,000. Then came the War of 1812 (1812-15), the Creek War (1813-14), the Creek Civil War (1813), the First Seminole War (1818-19), the Second Seminole War (1835-42), the Scare of 1849-50, and the Third Seminole War (1855-58).

During the early 1800s the Seminole population in Florida remained fairly small—around 1,200—compared to the main body of Creeks in Georgia and Alabama, who numbered possibly 25,000. Then came the War of 1812 (1812-15), the Creek War (1813-14), the Creek Civil War (1813), the First Seminole War (1818-19), the Second Seminole War (1835-42), the Scare of 1849-50, and the Third Seminole War (1855-58).  One other story became very personal for me and my support staff: that of Charlie Steel Gopher.

One other story became very personal for me and my support staff: that of Charlie Steel Gopher.