|

|||||||||

|

July/August 2013

Keynote to Keystone: The Bonior Speech On November 7, 1983—nearly thirty years ago—Rep. David Bonior November 7, 1983 I am honored to be here today at the first convention of Vietnam Veterans of America. You—American’s Vietnam veterans—have yet to receive the recognition you earned. Although the nation has not always listened, you have something to say and not just about veterans’ benefits. You have something to say about our nation’s values and its place in the world. Yet now, as in Vietnam, you will have to fight your own battles. No one else will volunteer to enact your benefits. And surely, no one else will rush forward on his own initiative to learn from your experience. You must commit to each other in order to help each other. You must make it happen for yourselves. That is the role of the Vietnam Veterans of America. I am honored to be here today because I want to be part of that effort. The Vietnam Veterans of America can give you a new voice. It can be your podium, and it can be the force that helps you win the benefits are long overdue. It hardly seems six long years since I first met [VVA founder] Bobby Muller. In a small, one-room office on Connecticut Avenue, Bobby was just a single person with an idea pitched against nearly the entire veteran establishment. In the years that followed, the Vietnam Veterans of America went broke more times than I can count. But one thing remained constant: The Vietnam Veterans of America was the one organization that would not be silenced, that would not forget, that would—at any price—remain always faithful. There was no easy solution. There were no simple clichés that would dispel controversy, no way to buy friends by abandoning the most difficult issues. Every issue was difficult, every sentence was controversial because each forced home a debt the nation did not want to pay. For over 200 years, this nation revered its warriors who joined battle against those who sought, through force, to alter our chosen way of life. Today, places like Yorktown, Verdun, and Omaha Beach are objects of pilgrimages for those who never experienced their glory, yet feel a sense of intangible gratitude to those who did. The veterans of these conflicts, while experiencing a wide disparity in readjustment benefits, all received the most valuable yet most intangible of benefits: the almost unanimous gratitude and adulation of their countrymen. On August 7, 1964, the House of Representatives, presumably with the overwhelming support of the American people, voted 416-0 in favor of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which gave the President a free hand for military action in Southeast Asia. Both the Congress and country have since been considerably less enthusiastic in their support for those they committed to the Vietnam War. While deploring that apathy, I can understand it. Vietnam was a war nobody wanted, in a land nobody knew, fought against a foe nobody understood. It was a war that lacked clarity of purpose, and in the end, it was, characteristically, not lost but unwon. The soldiers of this conflict were equal or superior to soldiers of past conflicts. They were generally better educated, better trained, and had a far lower battlefield rate of breakdown or desertion than their counterparts of World War II. The house-to-house battle for Hue, the murderous shelling absorbed at Khe Sanh, tested the courage of our soldiers no less than the battles of previous conflicts. But if the conflict was the same, the combat was not. As Phil Caputo wrote in A Rumor of War: The Vietnam War was mostly a matter of enduring weeks of expectant waiting and, at random intervals, conducting vicious manhunts through jungles and swamps where snipers harassed us constantly and booby traps cut us down one by one…Without a front, flanks, or rear, we fought a formless war against a formless enemy who evaporated like the morning mist, only to materialize in some unexpected place…Most of the time nothing happened, but when something did, it happened instantaneously and without warning. In 1981, the Veterans Administration released the results of a multiyear, multimillion dollar independent study of the actual readjustment of Vietnam veterans. Listen to the results: 60 percent of those who served in Vietnam faced readjustment problems on their return. For 40 percent, the problems remain.

While 34 percent of their non-veteran male peers have professional or technical jobs, for Vietnam veterans the rate is only 19 percent. During the year of the study, black Vietnam-era veterans faced an 11 percent unemployment rate, while black veterans who had served in Vietnam faced a 22 percent unemployment rate. In the last few years, we have begun to make progress. After years of foot-dragging, in 1981 the Congress passed health care for Agent Orange problems. The Delimitation Date was extended—although only for job training programs—and this year Congress has enacted a stronger Emergency Jobs measure. In 1979, the nation came together in one brief moment of recognition—Vietnam Veterans Week. Today, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial is nearly complete. Yet there should be no illusion. Our accomplishments are real, but they are also limited. Vietnam veterans are still an afterthought in American politics. Your needs are addressed only so long as it is convenient. H.R. 1961, the Agent Orange Compensation Act, is a limited and responsible measure. It addresses just three disabilities. There is substantial science in support of each. It will cost just $4 million in its first year. Yet today, the Congress is immersed in a long battle over H.R. 1961. The administration opposes the bill. Passage in the Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committee seems uncertain. We will win, but we must also be candid. We have a long way to go. It is crucial that the nation continue to meet its obligations to Vietnam veterans, but this organization cannot become just one more interest group scrambling for more benefits. Vietnam veterans cannot become just one more segment of the “me-generation.” Benefits alone will not give dignity to your years of waiting and your mighty sacrifice. When the veterans return from the next war—be it Grenada or Lebanon—Vietnam veterans must be in the forefront, ensuring a generous GI Bill. Let Vietnam veterans make the solemn vow that never again will one generation of veterans abandon another. You and I might disagree on the wisdom of the recent invasion in Grenada, but no one can doubt that the veterans of our nation’s last war have a role to play in advising the nation on future battles. You and I might disagree on the wisdom of stationing and sustaining a U.S. troop presence in Beirut, but no one can doubt that Vietnam veterans have the experience necessary to judge whether the deaths are justified. Our nation’s great tradition of a civilian military bottoms on the belief that the citizen-soldier returns from battle better prepared to measure its nation’s policies. How can our nation learn from the Vietnam War if Vietnam veterans—those who bear most personally the war’s experience—are not participants in the great policy issues that face our people? And if you, America’s Vietnam veterans, will not forcefully claim that role for yourself, then who else will give it to you? I am constantly puzzled as to why it has been so difficult for this nation to honor its debts to Vietnam veterans. We have study after study confirming the need, we have declared the priority in Congress, and the nation—as reflected in poll after poll—is prepared to act. We are aware that the nation faces rough fiscal times, but there are moral obligations which transcend budget requirements. I am convinced that the willingness to face these obligations, despite fiscal pressure, separates statesmen from politicians. The words of Abraham Lincoln, “To care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow and orphan,” must take on a new meaning in this nation or our patriotic declarations will ring hollow indeed. If we know who to call upon in time of war, then we should remember who to thank in time of peace. I thank you for coming to this convention today and giving me a chance to join you in the task ahead.

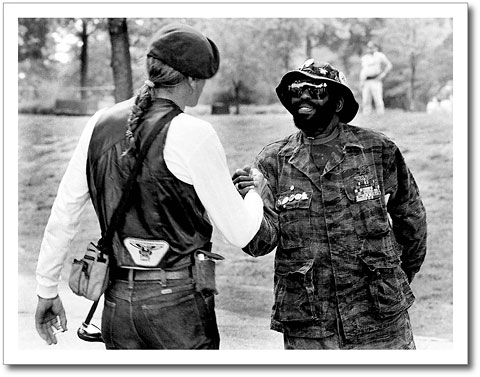

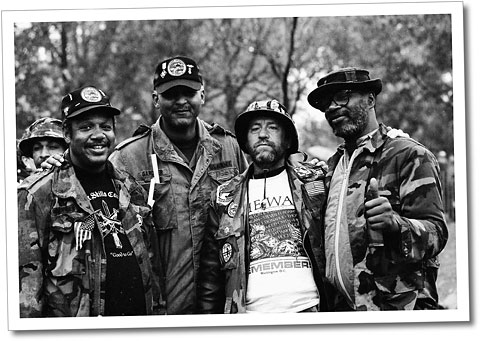

Adam Misztal’s Home from Pharaoh’s Army, a collection of his photographs of Vietnam veterans, is available at blurb.com Misztal can be reached at a.misztal@hotmail.com

|

|||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

|||||||||

Low GI Bill payments closed Vietnam veterans out of a college education. Even today, non-veterans are over 100 percent—100 percent—more likely to have a college degree. That educational advantage has now translated into a career advantage:

Low GI Bill payments closed Vietnam veterans out of a college education. Even today, non-veterans are over 100 percent—100 percent—more likely to have a college degree. That educational advantage has now translated into a career advantage: