|

|||||||||

|

July/August 2013 Artist Gregory Perillo: Fulfilling a Promise & Honoring BY BOB HOPKINS

Gregory Perillo is a renowned painter and sculptor. His portrayals of the American West and his self-professed love affair with Native Americans have earned him national and international accolades. His oil paintings are displayed in some of the most prestigious art galleries in the world, in centers of American commerce, and even in the Kremlin. Perillo was born to Italian immigrants who embraced American culture. His father quickly became proficient in English, immersed himself in American history, and encouraged his son to read as much as possible. He also told stories about the American West—some factual, others conjured. Perillo was often sent to the library to learn about the West and Native Americans. From an early age Perillo exhibited a flair for painting. “My first sketch was at age five. It was of Chief Tecumseh, after my father told me about the War of 1812. I did it on a brown paper bag,” Perillo said. “When I got in school they had white paper, and I brought some home. I wanted to do watercolors, and my mother gave me espresso coffee to use. I learned shading and tones from that.” Perillo left school to join the Navy in World War II. He served on the U.S.S. Storm King, a troop transport. “I was seasick for two years,” he said with a laugh. After his discharge Perillo used the GI Bill to start his formal training. He was the only artist mentored by William Robinson Leigh, an American painter who specialized in Western scenes. He married “the love of my life,” Mary Venitti, and had a son and daughter. He gained acceptance as an accomplished artist, often visiting and staying with Indian tribes, gaining inspiration and broadening his subject matter. When Perillo was going through Battery Park in the late 1960s on his way to a one-man show of his paintings at the midtown Wally Findlay Galleries, an incident happened that left an indelible mark on his spirit. “There was a Vietnam vet there with his wife and young child, sightseeing,” Perillo said. “War protestors came up to him and cursed at him and threw coffee cups at him. I stepped in to defend him. I was disgusted by what I saw. I vowed that some day I’d tell the true story of these heroes through my paintings.” Over the ensuing years, the artist continued to garner fame and recognition. He spent longer periods of time visiting Indian tribes and began sculpting. Still, there was a gnawing feeling, an unfulfilled promise he had made to himself. “I had to get it on canvas, and in 2002 I told Mary I was going to paint Vietnam veterans,” he said. “I would show their heroism, sacrifice, loneliness, and patriotism.”

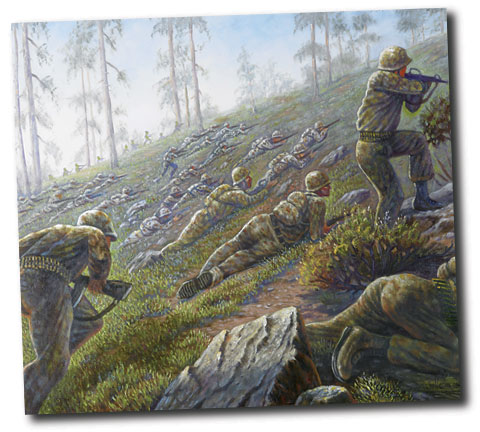

Over the next few years, Perillo created forty-two paintings and a bronze sculpture. He entitled the body of work Unsung Heroes. At a showing of his paintings at Wagner College he talked with Danny Ingellis, a retired police officer and Vietnam and Gulf War veteran. Ingellis was a member of VVA Chapter 421 on Staten Island, which is named in honor of Thomas J. Tori, who was killed in Vietnam. “I trusted Danny. He was a New York type of guy,” Perillo said. “I asked him to help me find a place to donate my paintings. It had to be the right place, and they couldn’t sell them.” Ingellis had been to the New Jersey Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial and Educational Center on several occasions. He approached Bill Linderman, the executive director, and Sarah Hagarty, the curator, and arrangements were made to have Perillo visit the site. He knew immediately that this was the perfect setting to display his works. His paintings, valued at $1.7 million, were donated to the Center and all reproduction rights given to its foundation to aid in fundraising. On September 28, 2012, a public exhibition reception was held. The memorial, Perillo said, was the perfect setting that he had envisioned for his paintings. The collection evokes many—often conflicting—emotions. From the sheer weight of physical and mental exhaustion in “Combat Fatigue” (reminiscent of James Earle Fraser’s sculpture, “The End of the Trail”), to the exhilaration of “After the Battle,” to the unseeing eyes of “The Sentinel,” Perillo has captured the essence of Vietnam War combat. He also has honored several Staten Island veterans, some of whom did not make it home. The promise made at Battery Park those many years ago has been fulfilled. Posters and framed reproduction prints from Gregory Perillo’s Unsung Heroes collection are available through the Foundation’s site at www.njvvmf.org/store.html or by calling 800-648-8387, ext. 100.

|

|||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

|||||||||

He’s outgoing, full of life, passionate about his work, and generous to a fault. There is no pretension in the man. He greets you like a long-lost friend, even though you’ve never met. It’s difficult to believe he’s eighty-five; there’s just so much energy bottled up. Yet, when he recounts the incident that occurred in Battery Park, N.Y., during the height of the Vietnam War protests, his voice suddenly lowers, his mood subdued.

He’s outgoing, full of life, passionate about his work, and generous to a fault. There is no pretension in the man. He greets you like a long-lost friend, even though you’ve never met. It’s difficult to believe he’s eighty-five; there’s just so much energy bottled up. Yet, when he recounts the incident that occurred in Battery Park, N.Y., during the height of the Vietnam War protests, his voice suddenly lowers, his mood subdued.