|

|||||||||||

|

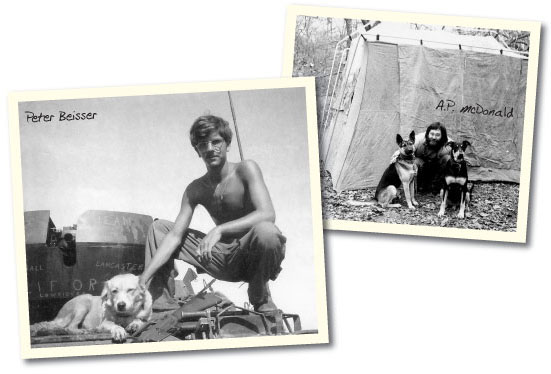

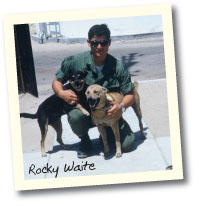

January/February 2013 Fur, Fangs, & Feathers: The Assorted Pets For most of the young American men and women serving in Vietnam, it was often a lonesome experience. They were homesick. Days were filled with long hours of tedium or the terror of combat. Tight friendships offered a great deal of relief. Many also turned to pets. Vietnam was crawling with animals. Stray dogs and cats wandered through cities and village streets and skulked around base camps and firebases. Exotic animals were taken by servicemen from the jungles or else purchased from Vietnamese vendors. Whether owned communally or by individuals, pets were almost always a group experience. Sometimes the animals were named the unit mascot. But most often they were simply companions. Pets varied from the domestic—dogs, cats, goats, pigs—to the exotic—monkeys, mongooses, birds, snakes. Soft, lovable animals were most common, especially dogs and monkeys. But even not-so-cuddly animals such as snakes and hawks provided calm and relief—or at least entertainment. There were problems, of course. Animals can carry and spread parasites and diseases. Also, pets were not immune to the dangers of war. Many were killed, fell ill, or died in accidents. Unlike in contemporary wars, in nearly all cases those serving in Vietnam had to leave their beloved pets behind. Not surprisingly, dogs were the most common pets in Vietnam. Dogs generally crave human attention, so strays hung around even remote firebases. Servicemen and women knew that some Vietnamese ate dog meat, a fact that was hard—so to speak—for many to swallow. Some took in or purchased dogs with the intention of rescuing them from becoming a meal. Often, too, dogs simply forced their way into the men and women’s lives. Brian Jones’s dog Kilo adopted him while he was serving as a company clerk with the Army’s 1st Signal Brigade’s Command Communications Company in Long Binh. “I just opened my hooch door one morning, and there she was,” Jones said. Her owner from another company came and got her. But over the next several days she kept coming back. Finally the owner said to Jones: “She loves you, so keep her.” Jones and Kilo became inseparable. Kilo slept under his desk in the company orderly room while he worked, rode shotgun in his jeep, and ate with him in the mess hall. Like Kilo, many dogs became regular members of a group. Sometimes they were even given official titles or dog tags. They often accompanied the men everywhere and ate and slept with them. Richard Grube had a dog, Sugar, while serving as an ambulance driver with the 3rd Field Hospital. Sugar rode along with him in his ambulance and watched John Wayne movies with him and the rest of the guys. “When we’d boo the bad guys,” Grube said, “she’d bark with us.” Andy the bloodhound, the mascot of the 615th MP Company “Bloodhounds” in Long Binh, was flown to the unit from the States with a group of scout dogs. Upon his arrival, he was greeted by an MP honor guard and escorted to the unit. He eventually was promoted to the rank of honorary captain.

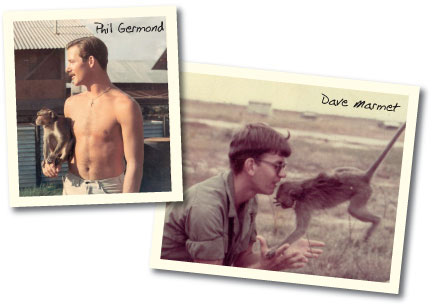

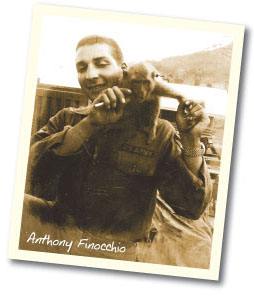

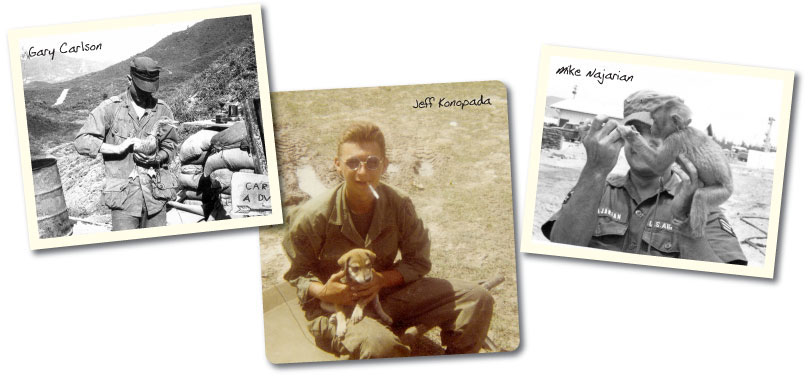

Frank Gale, who served with Detachment 7 as a helicopter door gunner with the Ha(L)-3 Seawolves, had a dog, Squiggles, who was his constant companion. She would greet him and his crew at the helicopter pad the moment they landed after returning from missions. “Having that dog brought normalcy to my life and those who were on the Detachment,” Gale said. “She had a calming effect on all of us and was something we could express love to and get instant feedback from. Important for guys who were flying into harm’s way every day.” Many who had pet dogs in Vietnam said they reminded them of home, either because they had grown up with dogs or simply because of the constant company and love. Don Dodson, who had a dog, Ward, while serving with the 4th Infantry Division Band, said his dog “helped us cross the huge mental divide from ‘back in the world’ and Vietnam. It was a therapeutic reminder of home.” Monkeys were also common pets. Monkeys, like dogs, can make very loving pets. Some were sold in markets, although others were simply found. Anthony Finocchio was serving with the 1st Cavalry in Ahn Khe when he found a small baby monkey that had been left behind in the jungle. Finocchio picked him up, put him in his pocket, and took him back, where he fed and cared for him. Once the monkey was older, he tried to set him loose in the jungle, but he wouldn’t leave. “That’s why we called him ‘Chief,’” Finocchio said. “Because he did whatever he wanted to do.” Being primates, becoming one of the guys was especially easy for monkeys. They often joined in drinking parties. Phil Germond described his pet monkey Mojo, whom he had while serving with the 44th Med. Brigade in Long Binh, as “a connoisseur of Schlitz beer.” Will Abshire’s monkey George enjoyed beer so much that, Abshire said, “Upon hearing a beer can open, George would jump on the arm of the soldier opening the can and demand his sip.”

Sweet Pea, a monkey in Dave Miles’s company area at LZ Snoopy while he was serving with C Company, 39th Combat Engineers, also bit when she was irritated. “Sweet Pea was a very playful monkey until you turned to walk away from her,” Miles said. “She would grab you by the thigh and bite you on the buttocks. The 39th Engineers’ CO was visiting our LZ one day and noticed Sweet Pea. Naturally, he thought she was cute and played with her for a while. When he turned to walk away, Sweet Pea bit him on the ass.”

Many species were kept as pets. The 559th Squadron of the 12th Tactical Fighter Wing at Cam Ranh Bay had a small black goat named Cadet C.L. Masters as a mascot. The 1st Platoon of the 192nd Assault Helicopter Company had an especially unusual mascot, a de-scented skunk named Waldo. Waldo had joined the platoon at Fort Riley in 1967. He traveled with the company across the Pacific from California to Cam Ranh Bay. “He caused quite a stir when he was allowed to take a walk on a leash aboard the ship,” Bill Lorfing remembers. When the unit moved to its first station, Phu Hiep, Waldo was “promoted” Birds were often kept as pets. John Dorn remembers a pet duck he encountered while serving with the 101st Airborne and 5th Special Forces. As Dorn was helping the Big Red One load deuce-and-a-halfs and materiel onto C-130s, he said, “one of the guys walked up to me and asked if they could bring their mascot on the plane. I asked what it was. He replied with a loud whistle, and to my surprise, here came a white duck. That duck walked up the ramp of that C-130 like he owned it and fluttered up onto one of the deuce-and-a-halfs.” While serving with the 86th Combat Engineers in the 9th Infantry Division in the Delta, Gary Smith found a hawk with a broken wing. He threw a shirt over the hawk to capture it, and nursed it back to health. “In the beginning, it just wanted to claw or bite me,” Smith said, “but eventually it came around to accept me helping it.” Smith frequently took the hawk out to exercise its healing wing. One day it took flight and left. Native mongooses were common pets. While serving with the 24th Evac. Hospital, Louis Ciaglia carried his pet mongoose Cynthia around in his pocket or on his shoulder. She slept under his bunk or at his feet. “We spent many a day just hanging out together,” Ciaglia said. “She was a great friend at a bad time.”

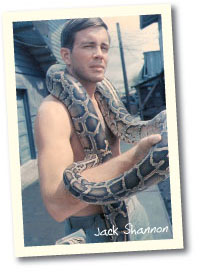

Snakes were often kept as pets, especially pythons, which are indigenous to Vietnam. Indeed, pythons were more local than most would have cared to know, as Jack Shannon found out while serving with MACV Advisory Team 50. “One night during the summer our Mekong Delta compound came under attack,” Shannon said. “Rudely awakened from my sleep, I attempted to make it to the safety of a bunker. Because of the havoc and debris in the air, the bunker seemed a bit too far away. I took shelter in a small dugout. Something like the Loch Ness monster arose in the darkness and looked me straight in the eye and froze me all the way to my nether parts. “I spent some time locked by the gaze of those obsidian eyes, and slowly came to the realization that I was caught in a foxhole with a snake. Deciding if it was safer in or out of the hole was a difficult call. Neither of us had made a false move, so I stayed—and so did the snake.” After their surprise meeting, “we became friends,” Shannon said. He kept the snake, who was apparently of very mild temperament, and named him Nate.

Pets’ antics provided lots of entertainment. Monkeys in particular, with their surprisingly human-like behavior, gave the men plenty of laughs. JoJo the monkey hung around with Dave Marmet and Charlie Company, 1/18th Infantry, 1st Infantry Division at Di An. “I remember him jumping onto the back of a dog and riding him around like a little jockey,” Marmet said. “Seems like he was always doing something funny, and I enjoyed the laughs. It was nice to get my mind off what was going on.” Pete Petrosky and his friend Robert Skaggs had a monkey, Bill, while serving with the 3rd Transportation Squadron motor pool in Bien Hoa. During a celebration on the Fourth of July they lit a firecracker and put it next to Bill to tease him, but the monkey picked it up and put it in his mouth like a cigarette. When they all yelled, “No, Bill!” he dropped the firecracker and it went off. Perhaps in revenge, Bill ran over to Petrosky and bit him. Snakes also provided plenty of entertainment. Watching them feed was a particularly popular event. Chris Green and others attended many feedings for Sam, the python who lived on a patio at the MACV building in downtown Ben Tre. “Many an early evening we would spend on the patio as the housekeeper placed an unlucky live animal in Sam’s cage,” Green said. “With cocktail or beer in hand, we watched the morbid scene, a prey-and-predator dance, as Sam maneuvered his eight-foot length, waited, and finally grabbed and squeezed the frantic hen or duck.” The 2nd “Snake” Platoon, 101st RRC at Engineer Hill was so nicknamed because of its pet Burmese python Dufas, whose weekly feedings became very popular, Tino Banuelos remembers. “We received word that one of our high-ranking officers and a local VIP would be visiting at the time of our next feeding,” he said. “This did not sit well with the men of the Snake Platoon, because the only time we were visited by personnel from the headquarters was for some type of inspection. When they showed up, the snake was found to have a large lump, which indicated that he had eaten a chicken the night before the visit. This made our visitors upset, because they knew that there would be no chicken-eating show. “Even so, another chicken was dropped into the crate. The chicken ran around and squawked, but the snake took no interest in it. Finally the visitors went back to the airbase and off to Davis Station after a stern lecture about sabotage and respecting protocol.”

“Being as the photographer was sweating, he didn’t immediately recognize that his right buttock had been liberally moistened. Ward wandered away, and a minute or so later the guy jumped up, grabbed his butt, and let out a very loud oath. Those were the wonderful moments that kept us all somewhat less insane while in Vietnam.” ON WATCH

Pets often helped with pest control. Don Dodson’s dog Ward was fond of hunting rats. Some pet mongooses also hunted rodents. Bill, Pete Petrosky’s pet monkey, helped keep the spider population down in his hooch. Bill enjoyed going up into the rafters to hunt and eat them. Petrosky would even rent Bill out to men in other hooches so he could eat their spiders. Before he grew up to become the Snake Platoon’s major attraction, Dufas the python had a different job. The platoon had a serious rat problem. One night Spec 5 McMann was woken by a rat sniffing his ear, and decided he’d had enough. He and a couple other men went to Saigon and purchased Dufas as a juvenile. They brought him back and released him down a rat hole. “Within a day or two,” Tino Banuelos said, “there were no rats scurrying around. Dufas had scared off those he could not catch.”

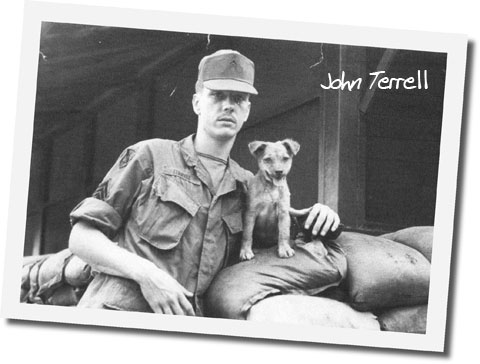

Some pets were injured or killed by the enemy. Fred Stevens had a terrier named Butch while serving with Bravo Company, 523rd Signal Battalion, Americal Division. One day Butch walked into a trip-wired booby trap and lost a leg and a tail, and sustained internal injuries. Butch was fortunate, though, in that the Americal’s veterinarians in Chu Lai were able to tend to his injuries and save him. Stanley, the canine mascot of Headquarters Troop, 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment’s Scout Section, often rode along on jeep convoys. On one ride with Jeff Williams, however, they were hit by an enemy Claymore and both were ejected. Williams was only slightly wounded, but Stanley suffered severe shock and permanent nerve damage. Many pets were killed or injured in accidents. Jose Hernandez’s kitten Knudsen, at the 1st Marine Air Wing in Chu Lai, was accidentally stepped on. His injuries were so severe that he did not survive. “It was so sad,” Hernandez said, “because everyone loved him.” John C. Terrel said that when his dog Ralph was run over by a jeep, “I lost my best friend and companion.” While serving with the Army Nurse Corps at the 85th Evac. Hospital, Judy Katz adopted a kitten, Dig It. The nurses’ compound was fenced, so Dig It had the run of the area. One day, however, a gate was left open and a stray dog got in. “The dog attacked my sweet little cat and broke her back,” Katz said. “It was so pitiful. She cried and cried, as did I, and we had to give her an overdose of anesthesia to put her to sleep.” Aside from carrying fleas and other parasites—which could infest the men and women and their living spaces—pets could also succumb to and even spread disease. While serving with the Marines in Da Nang, Sal Esposito’s puppy Cong fell ill, possibly with distemper, and died. “I think of that time and being helpless to aid him, and tears come to my eyes even now,” Esposito said. One of the gravest concerns was rabies. In many cases orders were given to get rid of all pets due to the threat. When Dennis Walden was serving with the 554th Engineer Battalion, a dog, Blackie, was looked after by several men at Thunder III Firebase near Chon Thanh. The unit had to move to Bao Loc, and due to worries over rabies they were not allowed to take any pets along. The dog had never been inoculated. One GI tried to smuggle Blackie when they moved out, but it was discovered by a company commander, who shot the dog on the spot. There were incidents involving pets contracting rabies. Thomas E. Sommerhauser, while serving with the 2nd Battalion Mechanized, 2nd Infantry of the 1st Infantry Division, returned to the battalion perimeter one day to find the unit’s pet dog Bierbaum lying on his side with his mouth foaming. Following standard operation procedure, Sommerhauser called his platoon leader to ask permission to use a .45 to put the rabid dog out of his misery. The platoon leader did not authorize it. “And so it fell on me to brain the pup with a log,” Sommerhauser said. “For about a week hardly anybody would talk to me.” When Mike Najarian was serving with the 14th Service Squadron, 14th Air Commando at Nha Trang Air Base, the unit had a very friendly dog, Charlie. One day, after a movie was shown, Charlie hunkered down under the projector and would not come out. Someone tried to pull her out, and she bit him. It turned out that she had rabies and had to be put down. The man she bit had to undergo a series of painful rabies shots. NOT GOING HOME Unlike the men and women serving in today’s wars, who often arrange to take their wartime pets home, that was virtually unheard of in Vietnam. Brian Jones and his dog Kilo were inseparable in Vietnam. He said that leaving Kilo behind was one of the hardest things he had to do—and hard for the dog, too. A buddy had to hide Kilo so that she would not follow Jones off the base when he left for home. Most handed their pets down to a buddy when it was time to return home. Will Abshire’s monkey George made the choice for him. “My fondest memory of George was seeing other soldiers’ faces light up when they first saw him,” Abshire said. “George was a godsend. He was friends with everyone.” But one day George disappeared. A couple of days later, a soldier came up to Abshire with George on his arm, asking if it was his monkey. “I saw the way George was holding on. From the look of his fatigues, I could tell the soldier had not been in country for very long,” Abshire said. “I told him the monkey’s name was George, and he could have him. I could see that George was happy with his new friend. As they walked away, George never looked back. I knew that was the right time to let go.” Tony Molina luckily was able to send his dog Itty Bitty home. He received permission to go to Saigon and ship her home, and had no problems getting the necessary paperwork from the Vietnamese government. Molina had to pay $200, and Itty Bitty was given the necessary shots and shipped to his parents in California. It was more complicated for A.P. McDonald to get his dog Newt home. As his DEROS date neared, McDonald started to think about taking Newt home. He knew a veterinarian and passed the idea by him. About a month later, the veterinarian told him, “I doubt you’ll be able to pull it off. But if you do, you will need this,” and handed him legal entry papers he had signed, stating that the dog had been quarantined. McDonald had a 1st Marine Aircraft Wing press card stating that he could commandeer rides on any aircraft as a combat photographer. He knew that if he could get to Saigon, he might be able to ship Newt to the States. With his future replacement covering for him, McDonald started hopping rides to Saigon with Newt. He had typed up fake papers that appeared to be orders to have the dog transferred to Saigon for further training as a scout dog. Despite a few suspicious officers along the way, they made it to Saigon. Once he arrived at the airport, McDonald found out he needed Vietnamese export papers to send Newt home. He went to the office where he needed to get the papers. McDonald was carrying his “blood money”—five $20 bills. He put all five bills on the counter. The man smiled, shook his hand, and signed the papers. McDonald took Newt back to the airport and had the dog shipped to his mother in Indiana. McDonald’s mother picked Newt up, and McDonald was reunited with him when he returned home. Newt later traveled around the United States with McDonald in a motorcycle sidecar, and he lived to a ripe old age. But the vast majority of Vietnam veterans had to leave their wartime pets behind. Most carry the memories of their friends even today—warm, pleasant memories that counter other, bad memories of their time in Vietnam. Peter Beisser’s dog Lady at the 11th ACR often alerted him to the presence of Viet Cong, thus making him feel safe having her around. Beisser has a photograph of Lady, which he enlarged upon returning home. “It has hung in my hair salon for more than thirty years,” he said, “so that I can still see her every day and have that safe feeling.” Although Sal Esposito still suffers the pain of his pup Cong’s untimely death, pleasant memories remain, too. “He was so adorable and full of love,” Esposito said. “I cannot help but smile when I think of his playfulness. So many memories of that time in country come and go. Here, about forty-seven years later, that pup is still fresh in my mind.”

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

|||||||||||