|

|

BY LADY BORTON

“Dien Bien Phu was the bell tolling the death knell for colonialism.” —Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap, Dien Bien Phu: Rendezvous with History

On August 25 Vo Nguyen Giap will be 101. Although frail, Gen. Giap remembers everything. Each morning his personal assistant reports the news; his first son, Dien Bien, coordinates family visits.

Gen. Giap’s longevity is fundamental to Vietnamese viewpoints on the French War and the American War in Vietnam. His influence was curtailed during the Hard Times between 1975 and Doi Moi (Renovation or Renewal), which began in December 1986. Indeed, the hour-long, official 1984 Vietnamese documentary honoring Dien Bien Phu fails to mention Vo Nguyen Giap or Ho Chi Minh.

The Doi Moi years have been kinder to President Ho and Gen. Giap. Vietnamese show respect and intimacy by calling their nation’s founder “Uncle Ho” and its most famous modern commander “Older Brother Van” (“Van” is Gen. Giap’s nickname).

During the late 1930s Vo Nguyen Giap studied law, taught history, and edited revolutionary newspapers in Hanoi. A prolific writer, he specialized in political economy. Years later, as historian and retired general, he used amanuenses and retired officers as researchers for his books. Gen. Pham Hong Cu, eighty-six, was one of them. He says Vo Nguyen Giap usually wrote a dozen drafts but only eight drafts when hospitalized. During the late 1930s Vo Nguyen Giap studied law, taught history, and edited revolutionary newspapers in Hanoi. A prolific writer, he specialized in political economy. Years later, as historian and retired general, he used amanuenses and retired officers as researchers for his books. Gen. Pham Hong Cu, eighty-six, was one of them. He says Vo Nguyen Giap usually wrote a dozen drafts but only eight drafts when hospitalized.

As a young teacher, Vo Nguyen Giap added Vietnamese history to the French curriculum. Le Trong Nghia, a student at Giap’s school although not in his class, served as Commander of the Intelligence Department at Dien Bien Phu. He says Giap’s students learned that Vietnamese victories required quan va dan (the military and the people) and toan dan (all the people). They memorized poetry, including poet-strategist Nguyen Trai’s lines from 1428: “Take the small to fight the large. Take the few to fight the many.”

In May 1941 Ho Chi Minh and Party leaders met in Vietnam’s mountainous far north and formed the Viet Minh, a broad revolutionary front including patriots who were not communists. In December 1944 Ho Chi Minh asked Vo Nguyen Giap to form a main-force army. Most of the first thirty-four soldiers were ethnic Tay or Nung from mountainous Cao Bang. Hoang Van Thai, an early recruit from the northern delta, was Chief of Staff at Dien Bien Phu. Another early recruit, Le Quang Ba, commanded the 316th Division. Initially, their weapons were spears. Three months later in March 1945, following Ho Chi Minh’s meeting in Kunming with U.S. Gen. Claire Chennault, the Viet Minh army received its first modern light weapons from the OSS, the predecessor of the CIA.

Viet Minh patriots secretly organized the largely peaceful August Revolution, securing power during the political vacuum created after Japanese Emperor Hirohito’s surrender on August 15. Two days later a pair of youths raised the Viet Minh flag over the citadel in the imperial capital of Hue.

Nine years later one of them was deputy head of intelligence at Dien Bien Phu. Cao Pha died in 2006, but the other young man, Col. Dang Van Viet, is now ninety-two and rides his motorbike around Hanoi. By the late 1940s the French were calling him the “Tiger of Colonial Route 4,” which runs along the Vietnamese-Chinese border. He and his small unit ambushed French convoys and captured American-made French materiel. In 1950 the Viet Minh’s Border Campaign liberated Route 4, opening easy access for the Soviet and Chinese materiel used at Dien Bien Phu.

By 1952 the Viet Minh controlled the north and northeast; the French controlled forts in the northwest. At Na San, French Col. Jean Gilles built a “porcupine” base with armed outposts, trenches, and barbed wire. French success at Na San encouraged expansion of this model at Dien Bien Phu; Viet Minh failure led Gen. Giap to stop at Na San en route to Dien Bien Phu.

In the summer of 1953 French Gen. Henri Navarre presented his plan to bring the war to “an honorable end.” In September Soviet intelligence secured a copy of Navarre’s plan (complete with maps) and passed it to Chinese counterparts, who passed it on to the Viet Minh.

The nine-year-old Viet Minh army faced a far larger total French force. Vo Nguyen Giap credits President Ho with developing the Viet Minh strategy.

Ho Chi Minh used secrecy and humility to camouflage his knowledge. French and American leaders underestimated Ho’s expertise across many fields, including his extensive military training. According to Ho’s staff living today in Hanoi, between 1924 and 1927, while Ho Chi Minh was in Guangzhou as the Comintern (Communist International) organizer for peasant movements in Asia, he also served as the interpreter for the Russian military experts teaching at Whampoa Military Institute.

Interpretation requires a sharp memory and concentration on content. That interpretation assignment gave Ho Chi Minh a solid base in Russian and Chinese military theory. He also secured admission to Whampoa for young Vietnamese revolutionaries, most of whom were officers at Dien Bien Phu and during the American War.

In early October 1953 the four-member Politburo examined the Navarre Plan. As Gen. Giap tells the story, Ho held up his fist:

“‘The enemy is concentrating its mobile forces to create great strength,’ Ho Chi Minh said. ‘We needn’t be afraid. We’ll make the French disperse their forces. Their strength will evaporate.’ ”

Ho spread his fingers for the five initiatives that became the 1953-54 Winter-Spring Plan:

1) In the northwest, liberate Lai Chau, the provincial capital; with the Pathet Lao, liberate Phongsaly Province.

2) With the Pathet Lao, push into Central Laos.

3) With the Pathet Lao, liberate Attapeu and the Boloven Plain in Southern Laos.

4) Stage small battles in the northern Central Highlands to draw French troops from Operation Atlante.

5) Harass the French with guerilla attacks.

Once Gen. Navarre’s forces had dispersed, the Viet Minh army would fight a major battle against the French somewhere in the Northwest, where the mountainous terrain suited Viet Minh tactics.

The Viet Minh launched its offensives. Navarre responded, dispersing his forces as if receiving orders from Ho and Giap. The Viet Minh and the Pathet Lao liberated Phongsaly and Attapeu. The Viet Minh captured French posts in the Central Highlands, forcing Navarre to abandon Operation Atlante. In November Gen. Giap called a meeting of key officers to decide where to stage their major battle. The Viet Minh launched its offensives. Navarre responded, dispersing his forces as if receiving orders from Ho and Giap. The Viet Minh and the Pathet Lao liberated Phongsaly and Attapeu. The Viet Minh captured French posts in the Central Highlands, forcing Navarre to abandon Operation Atlante. In November Gen. Giap called a meeting of key officers to decide where to stage their major battle.

But between November 19 and 22, just as Gen. Giap was meeting with his officers, Gen. Navarre dropped 4,500 paratroopers into Dien Bien Phu. What would normally have caused the Viet Minh to despair became a reason to celebrate. The officers agreed that their battle should be at Dien Bien Phu.

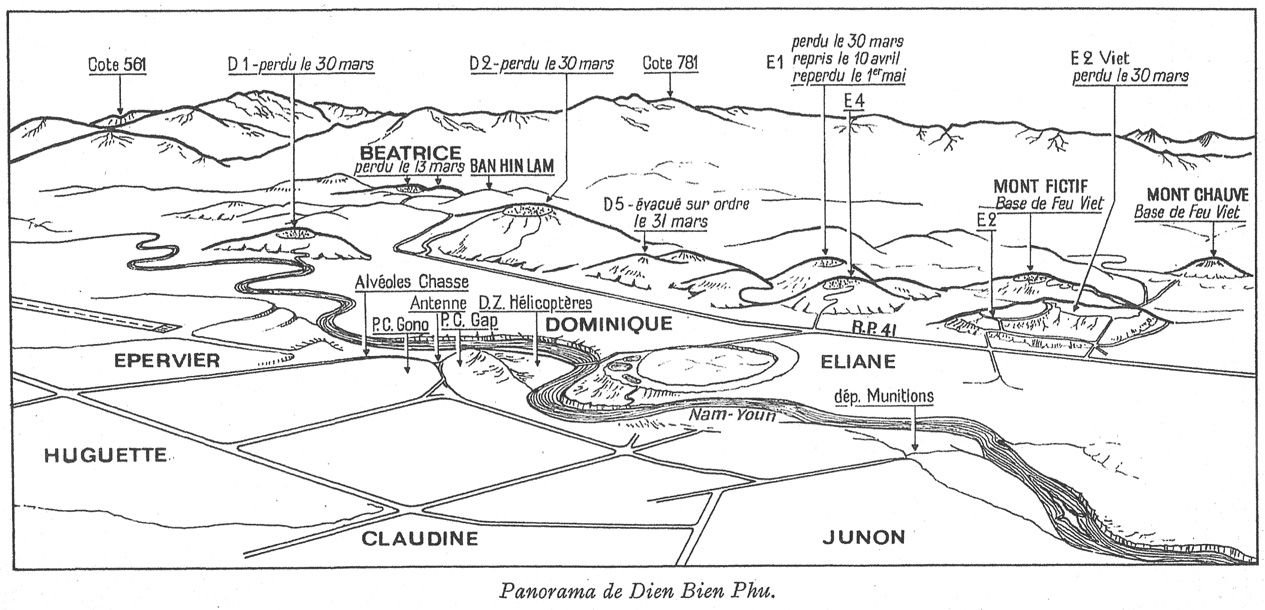

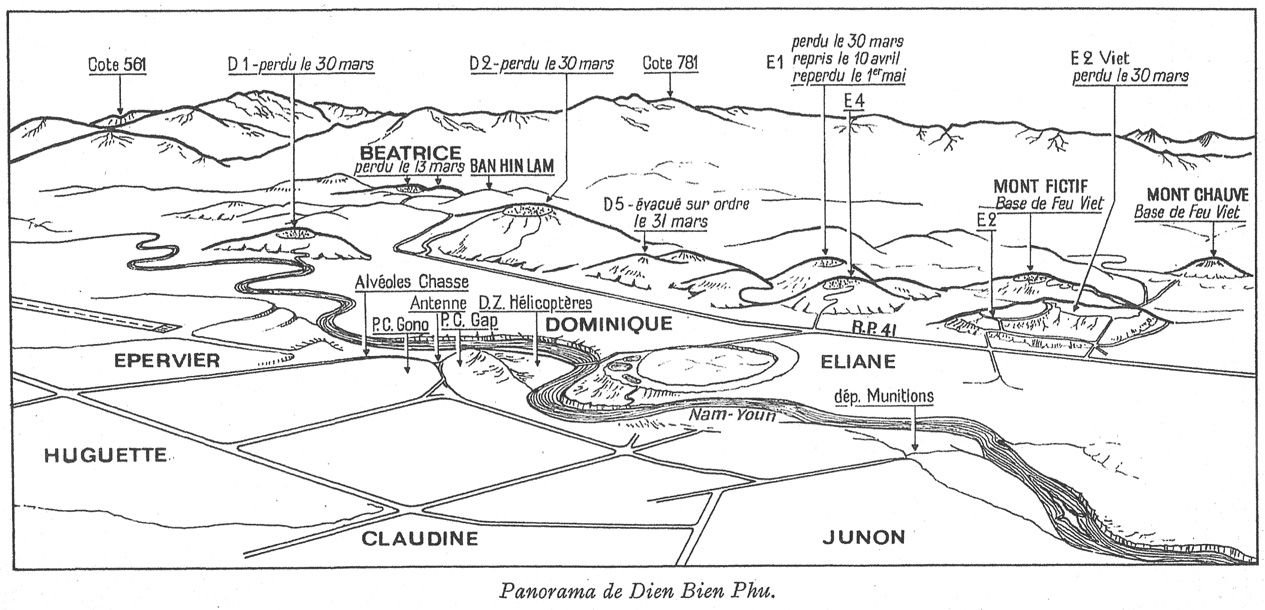

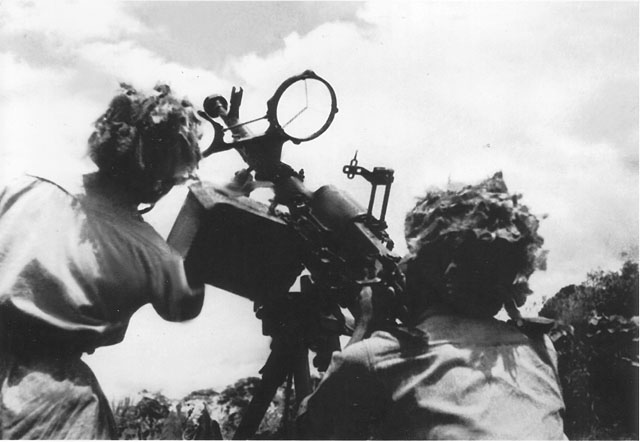

The Viet Minh’s map of the Northwest was blank, except for a dot labeled “Dien Bien Phu.” According to Le Trong Nghia, Gen. Giap dispatched scouts with artillery binoculars having a ten-kilometer range. Local ethnic Thai patriots knew the best mountaintop outlooks. Day and night, the scouts trained their binoculars on the French camp, recording its details.

After careful study, on December 6, 1953, the Viet Minh Army High Command proposed to the Politburo that the army engage the French at Dien Bien Phu. The Politburo agreed.

Throughout the French War and during the American War, Ho Chi Minh used his writing skills in a presidential voice under his own name and also using pseudonyms. Ho was fluent in Chinese, English, French, and Russian, as well as in several ethnic-minority languages; he had monitored short-wave broadcasts for Chinese revolutionaries in Guilin in the late 1930s. During Dien Bien Phu he kept abreast of world news from multiple language sources.

On November 20, writing as “C.B.,” Ho Chi Minh published a poem, “The Navarre Plan—Head of an Elephant, Tail of a Dog.” On December 1, reporting as president to the National Assembly, he began his world-affairs section with remarks on Korea:

“This is the first time (but not the last) that the United States has suffered a major defeat…. The current American scheme is to provoke wars in order to become master of the world…. The [French] enemy’s primary design is ‘to use Vietnamese to fight Vietnamese and to use war to breed war.’… The United States is forcing France to become a puppet and plans to replace France at every step.”

That same National Assembly session implemented a decision essential to victory. Ho signed the Land Reform Law, providing peasants with their own fields and motivating their participation. Citizen laborers and army engineers built a truck road to the command headquarters, mountain tracks to the French “porcupine,” and access tracks to artillery sites. Peasant women hauled rice, ammunition, and medical supplies in baskets suspended from shoulder yokes. Peasant men pushed pack bicycles. Soldiers took apart heavy artillery, dragged the parts along muddy trails, and reassembled the guns on mountainsides circling the valley.

Vo Nguyen Giap went to see Ho Chi Minh in the Secure Zone before leaving for the battle. Ho reminded Giap: “This battle is crucial. You must fight to victory. Fight only if you’re sure of victory. If you’re not sure, don’t fight.”

The Battle Command had decided to strike at 5:00 p.m. on January 25 and finish in three nights and two days. As soon as Vo Nguyen Giap reached Dien Bien Phu, though, he saw that his troops were not ready. Still, his officers all supported the plan, “Fast Strike. Fast Victory.”

[click to enlarge]

The Viet Minh learned that the French had discovered their Zero Hour; Gen. Giap delayed twenty-four hours to confuse the French. Distressed, he realized he couldn’t guarantee victory. He asked his personal secretary, Nguyen Van Hieu, to research the situation and report back to him.

Then Pham Kiet, responsible for artillery at the western front, telephoned. “Our guns are exposed,” he reported. “If enemy airplanes or artillery strike, we’ll suffer huge losses. We still haven’t hauled in all our guns.”

Col. Hieu reported: “The ideological training has created tremendous determination but little discussion of overcoming battle difficulties.”

Early on January 26, convinced that he should abort the plan, Gen. Giap summoned his Chinese interpreter, Hoang Minh Phuong, now in his mid-eighties. Vo Nguyen Giap speaks Cantonese, but not Mandarin. According to Gen. Giap, convincing Wei Guoqing, head of the Chinese advisers, took a half hour. Yet without interpretation, the content would have taken fifteen minutes. Given two millennia of Chinese-Vietnamese strife, it defies psychological logic to believe that Gen. Giap needed only fifteen minutes to persuade his key Chinese adviser to abort the plan.

Col. Phuong, however, confirms the half-hour discussion. He and historian Pham Huy Le discovered that Wei Guoqing had sent a secret message to Beijing on January 25, worrying about failure, but hadn’t received a reply. It was in that context that Vo Nguyen Giap (and not the Chinese) made what the general calls “the hardest decision in my life as a military commander.”

Gen. Hong Cu’s name heads the list of researchers for Vo Nguyen Giap’s Rendezvous with History. “The memoir omits an important detail,” he says. “We must all understand the difficulty Gen. Giap faced. He was beholden to the four-member Party Committee for the Battle, which reached its decisions by voting. Gen. Giap was alone and outnumbered. He had three outspoken opponents.”

Vo Nguyen Giap describes the meeting:

“Everyone was quiet. Le Liem, Commander of the Political Department for the Battle, spoke first: ‘But we’ve given everyone his assignment. Our soldiers and officers are confident and determined. How can we explain such a change?’ “Everyone was quiet. Le Liem, Commander of the Political Department for the Battle, spoke first: ‘But we’ve given everyone his assignment. Our soldiers and officers are confident and determined. How can we explain such a change?’

“‘I think we should preserve our determination,’ Dang Kim Giang, Commander of the Supply Department, added. ‘The logistics work has endured countless hardships during the preparations. If we don’t fight now, we can never strike.’

“‘Older Brother Van has weighed this carefully,’ Hoang Van Thai, Chief of Staff, said. ‘However, we have troop superiority for the battle. For the first time, we have 105-mm artillery and modern antiaircraft guns. We’ll surprise the enemy. In addition, we have the experience of our Chinese friends. I think if we fight, we can win.’ ”

They haggled, took a tea break, then returned. Gen. Giap cited his conversation with President Ho:

“‘If we fight,’ I said to them, ‘are you 100 percent sure of victory?’

“‘Older Brother Van has raised a difficult question,’ Le Liem said. ‘Who dares say he’s 100 percent sure of victory?’

“‘How can anyone guarantee that?’ Dang Kim Giang said.”

Gen. Giap persisted, saying: “For this battle, we must be 100 percent sure of victory.”

The Party Committee agreed, and Gen. Giap ordered a complete withdrawal.

He sent his premier 308th Division racing into Laos as a feint. Gen. Hong Cu, then a regimental political commissar and, in 1975, the division’s political commissar for the final push into Saigon, remembers the sprint to Laos without provisions, how Lao villagers fed them, and how they pushed to within fifteen kilometers of the Laotian imperial capital before receiving the order to return. The ruse worked. According to Gen. Giap, the French command decided that the Viet Minh had abandoned Dien Bien Phu. But French bombing made hauling the heavy guns out more perilous than dragging them in.

The Viet Minh’s new plan, “Steady Attack. Steady Advance,” relied even more on toan dan (all the people) to serve the supreme general, the “Rice Commander.” Thirty-five thousand Vietnamese citizens used pack bicycles, horses, skiffs, and shoulder yokes to haul 27,400 metric tons of food and ammunition. They pushed or carried much of the rice six hundred kilometers from Thanh Hoa Province to Dien Bien Phu. The French supplied their troops by air with U.S. airplanes bearing French insignias but sometimes flown by civilian American pilots.

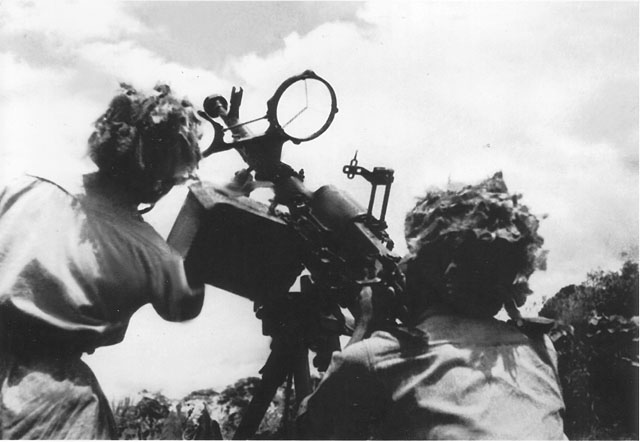

This time the Viet Minh hid artillery and antiaircraft guns in camouflaged bunkers. They built companion decoy nests with smoke bombs that would fire simultaneously, thereby becoming targets for retaliatory French strikes. According to Gen. Giap, French Artillery Commander Col. Charles Piroth had boasted: “No Viet Minh gun will fire three rounds without being destroyed.” This time the Viet Minh hid artillery and antiaircraft guns in camouflaged bunkers. They built companion decoy nests with smoke bombs that would fire simultaneously, thereby becoming targets for retaliatory French strikes. According to Gen. Giap, French Artillery Commander Col. Charles Piroth had boasted: “No Viet Minh gun will fire three rounds without being destroyed.”

Stage 1 began on March 13, 1954. Unbeknownst to the French, the Viet Minh troops had secretly set their 75-mm howitzers on the near sides of the mountains. They trained their howitzers on the French airfield, their decoy smoke bombs ready. The Viet Minh further surprised the French with antiaircraft and 105-mm artillery. Vietnamese ammunition was limited. However, the barrage was so overwhelming that on March 16 Col. Piroth committed suicide.

At 10:30 p.m. the first night, March 13, Viet Minh troops overran Him Lam (Beatrice). At 6:30 a.m. on March 15 they took Doc Lap (Gabrielle). On March 17 ethnic Thai soldiers who were fighting for the French surrendered Ban Keo (Anne-Marie 1 and 2).

Then the Viet Minh began Stage 2—the encroaching trenches tightening like a noose around the French Command Post.

Gen. Hong Cu’s unit, back from Laos, dug the trenches. Each night a thousand troops dug one kilometer. “The French shells landed all around,” Hong Cu says, “but except for a direct hit, we were safe. Each man dug one meter each night. Initially he lay on the ground and dug. Soon he could squat in his ditch. Other troops brought us rice. Before long we could stand in the trench and dig. Darkness and mud camouflaged us. We called ourselves the ‘seven white spots’—our eyes, our teeth, and five fingers whitened from licking off grains of rice.”

Hong Cu’s unit withdrew before daybreak. The regiment led by Pham Hong Son, who commanded the 308th Division during the American War, fought all day, defending the new trenches. Hong Cu notes that Gen. Giap particularly valued Hong Son during both the French War and the American War for his ability to prevent casualties.

The tightening trenches drew within a hand-grenade’s range of French troops. Mai Son, now in his mid-eighties, was an artillery officer with the 316th Division. He remembers intense discussions at battle headquarters about A1 (Eliane 2). The Viet Minh had lost nearly a thousand men in failed assaults. When Gen. Giap insisted intelligence officers learn why, local ethnic Thai peasants described digging a bunker in 1945 atop A1 for a Japanese wine cellar.

“Assault won’t work,” Gen. Giap said. “We must dig under A1 and detonate a ton of TNT under the bunker. How far is the bunker from our lines?”

“About fifty meters,” Le Quang Ba reported.

“‘About’ won’t do,” Gen. Giap said. “Precisely how far?”

Thirteen years before, Le Quang Ba and other ethnic Tay youth had guided Ho Chi Minh from China through Japanese lines and back to Vietnam after Ho Chi Minh’s thirty years overseas. Now Division Commander Ba crept with a measuring tape up A1 to the French bunker and back.

“Forty-nine meters,” he reported.

Mai Son designed the secret tunnel. But the division had only five hundred kilos of TNT. Engineers dismantled unexploded ordinance from an American B-24 bomber the Viet Minh had downed near Ban Keo (Anne-Marie 1 and 2). They harvested five hundred kilos of American TNT.

Gen. Giap describes the evening of May 6:

“We had ordered our fighters in the trenches penetrating into Eliane 2 to turn their backs five minutes before Zero Hour. They were to shut their eyes and open their mouths to prepare for the shock and flash from the one thousand kilograms of explosives we would detonate under the enemy bunker on Eliane 2. At 20:30 we heard an unexpected noise. A huge column of smoke rose from Eliane 2.” “We had ordered our fighters in the trenches penetrating into Eliane 2 to turn their backs five minutes before Zero Hour. They were to shut their eyes and open their mouths to prepare for the shock and flash from the one thousand kilograms of explosives we would detonate under the enemy bunker on Eliane 2. At 20:30 we heard an unexpected noise. A huge column of smoke rose from Eliane 2.”

Now, years later, Mai Son adds: “We could never have taken A1 and could never have won at Dien Bien Phu without that bomb.”

Stage 3—the assault on the French Command Post—began. Gen. Le Trong Tan, who later was the deputy commander for the final 1975 assault against Saigon, commanded the final assault at Dien Bien Phu.

According to Gen. Tan, Company Commander Ta Quoc Luat and two soldiers, Vinh and Nho, broke into Gen. Christian de Castries’s bunker. The French general’s first words to Ta Quoc Luat were: “Please don’t shoot me.”

Gen. de Castries surrendered on May 7, 1954. On May 8 both Gen. Giap and Ho Chi Minh wrote to soldiers and citizens, praising their victory. Ho noted: “Although the victory is great, we have only begun.”

Some Western scholars have criticized the Vietnamese for not releasing Vo Nguyen Giap’s post-battle report to the Politburo. The Politburo, however, consisted of four seasoned revolutionaries who took pains not to keep written records that could fall into enemy hands.

Vo Nguyen Giap’s report at a general evaluation meeting on July 28, 1954, notes: “The American imperialists took responsibility for 80 percent of the financing for all the Indochina War.” He analyzes the American strategy: “After achieving a decisive victory and turning Indochina into an American base, the American warmongers would have built Dien Bien Phu into their key Southeast Asian airbase, from which they could control the north of Viet Nam and the north of Laos and intimidate southwestern China.”

Years later Vo Nguyen Giap concluded his memoir:

“The work of peace drew us forward, but the general elections and other points in the Geneva Agreements were never implemented. Our people prepared once again for a new stage in the long march toward independence and unification. That long march would turn out to be more miserable than the one we had just completed.”

Lady Borton has received three honorary degrees for her forty-five years of work with all sides during and after the American War in Vietnam. She is at work on a revised and annotated translation of General Giap’s Dien Bien Phu: Rendezvous with History.

|

|

|

|

During the late 1930s Vo Nguyen Giap studied law, taught history, and edited revolutionary newspapers in Hanoi. A prolific writer, he specialized in political economy. Years later, as historian and retired general, he used amanuenses and retired officers as researchers for his books. Gen. Pham Hong Cu, eighty-six, was one of them. He says Vo Nguyen Giap usually wrote a dozen drafts but only eight drafts when hospitalized.

During the late 1930s Vo Nguyen Giap studied law, taught history, and edited revolutionary newspapers in Hanoi. A prolific writer, he specialized in political economy. Years later, as historian and retired general, he used amanuenses and retired officers as researchers for his books. Gen. Pham Hong Cu, eighty-six, was one of them. He says Vo Nguyen Giap usually wrote a dozen drafts but only eight drafts when hospitalized.