|

|

BY MARC LEEPSON

Indochina is “probably the top priority in foreign policy, being in some ways more important than Korea because the consequences… could not be localized but would spread throughout Asia and Europe.”

—Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, March 24, 1953

The United States played no direct role in the disastrous May 1954 French defeat at Dien Bien Phu. No American troops or advisers were on the ground at the remote outpost near the Laotian border. And despite insistent French pleas, no American bombers came to the relief of the 15,000-strong French garrison, which surrendered on May 7, 1954, after almost two months of pressure from a 50,000-man Viet Minh army under Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap. The French capitulated after weeks and weeks of Viet Minh bombardment using Chinese-supplied artillery and devastating human-wave attacks.

While it is true that no American military personnel took part in the battle the United States was France’s primary ally in its bitter nine-year struggle against the communist-led Viet Minh Vietnamese independence movement. Although officially neutral, the U.S. bankrolled the French war and supplied huge amounts of military hardware beginning in the late 1940s.

During the French Indochina War, which lasted from 1945-54, there was often contentious debate inside the Pentagon, the State Department, the White House, and on Capitol Hill about whether or not to send American fighting forces to help the French. Presidents Truman and Eisenhower, despite lobbying from the French and from some high-ranking American military and foreign-policy advisers, contented themselves with transferring large amounts of American money and aid to our French ally.

American financial help for France, in the form of billions of dollars in Marshall Plan funds, began flowing soon after World War II ended in 1945. That huge influx of cash allowed the French government to use its own limited funds to finance its war against the Viet Minh.

The United States sent an enormous amount of American arms and war materiel to Indochina. By early 1953 the list included some 900 combat vehicles, 15,000 other military vehicles, nearly 2,500 artillery pieces, 24,000 automatic weapons, 75,000 small arms, and some 9,000 radios. The Americans also provided French air units with 160 F-6F Hellcat and F-8F Bearcat fighter aircraft left over from World War II, 41 B-26 light bombers, and 28 C-47 transport planes, along with 155 aircraft engines and 93,000 pieces of aerial ordnance.

Even so, the French asked for more during the winter of 1953-54 as the Viet Minh noose tightened around the French garrison at Dien Bien Phu. The French only realized the precariousness of their situation in mid-March when the Viet Minh attacks began in earnest and the French began running short of ammunition, medical supplies, and food. On March 20, 1954, Gen. Paul Ely, the Commander in Chief of all French forces in Indochina as well as the French High Commissioner in Indochina, flew to Washington. His mission: To lobby the Eisenhower administration to send U.S. bombers to relieve the siege.

Some administration officials agreed with Ely and advised President Eisenhower to intervene. That group included Vice President Richard M. Nixon. During Ely’s visit, Adm. Arthur Radford, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Nathan F. Twining pushed for the implementation of Operation Vulture (Vautour in French), a plan drawn up by French and American military men in Vietnam. The operation’s ominous name fit its mission: a massive air assault on Viet Minh positions led by U.S. B-29 bombers, some of which would be equipped with nuclear weapons.

Nixon, who made his political reputation as a vehement anticommunist, went so far as to say that under the right circumstances he supported sending in American troops. “The United States is the leader of the free world and the free world cannot afford in Asia a further retreat to the communists,” Nixon said April 16 at an off-the-record talk at a newspaper editors convention. “I trust that we can do it without putting American boys in…. But under the circumstances, if in order to avoid further communistic expansion in Asia and particularly in Indochina, we must take the risk now by putting American boys in. I believe that the Executive Branch of the Government has to take the politically unpopular position of facing up to it and doing it, and I personally would support such a decision.”

But Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, also a staunch anticommunist, opposed Operation Vulture. Dulles “was deeply concerned that the Chinese might intervene in Indochina and that France might capitulate, and he was prepared to take risks,” Vietnam War scholar George Herring wrote. “Like Eisenhower, however, he appears not to have been convinced that Vulture was either feasible or necessary.”

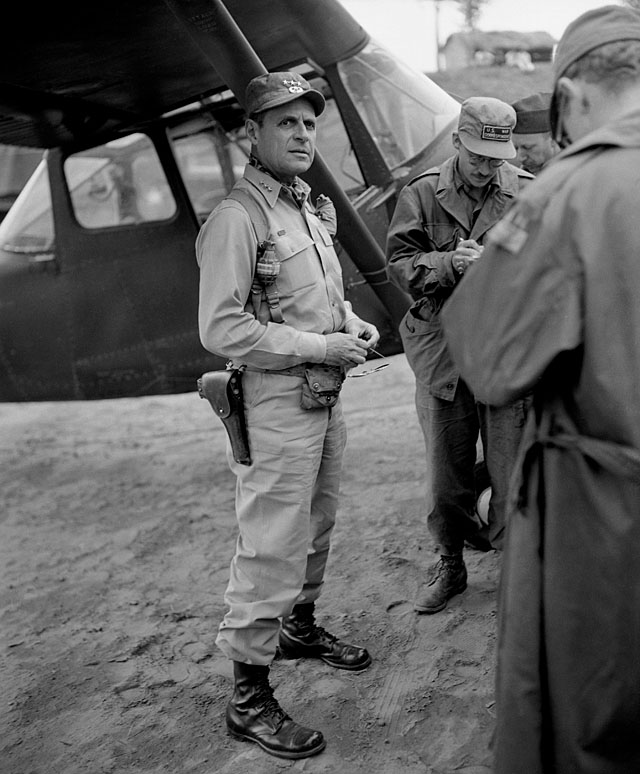

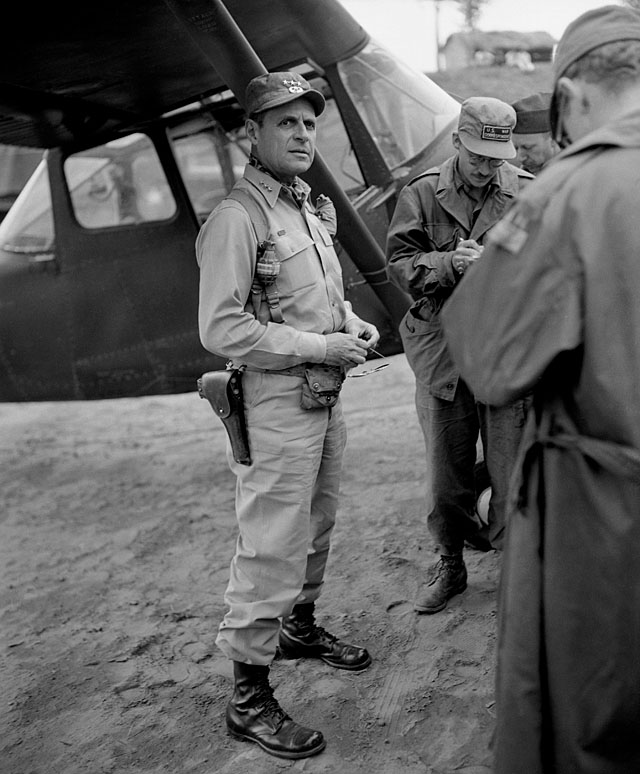

Several congressional leaders, including Senate Minority Leader Lyndon Johnson of Texas, spoke out against it. Army Chief of Staff Gen. Matthew Ridgway, a hero of the Korean War, and his Operations Chief, Gen. James M. Gavin, also advised against implementing Operation Vulture after sending a team of Army experts to Indochina to assess the French situation. Several congressional leaders, including Senate Minority Leader Lyndon Johnson of Texas, spoke out against it. Army Chief of Staff Gen. Matthew Ridgway, a hero of the Korean War, and his Operations Chief, Gen. James M. Gavin, also advised against implementing Operation Vulture after sending a team of Army experts to Indochina to assess the French situation.

The American military team’s report noted that the geography of Vietnam favored a guerrilla operation and that American air intervention would not quell the rebellion. The report also concluded that it would take ten U.S. Army divisions to defeat the Viet Minh. Ridgway was loath to do that because he did not want to divert U.S. troops from other hot spots around the world with the Cold War at its height and the military on alert to stop Soviet expansionism. He, too, was concerned the move would prompt Chinese intervention.

Ridgway called Operation Vulture “the old delusive idea that we could do things the cheap and easy way.” He also offered what turned out to be a prescient warning to President Eisenhower that air power alone would not defeat the Viet Minh. When “the day comes for me to face my Maker and account for my actions, the thing I would be most humbly proud of was the fact that I fought against, and perhaps contributed to preventing, the carrying out of some hare-brained tactical schemes which would have cost the lives of thousands of men,” Ridgway wrote in his memoir. “To that list of tragic accidents that fortunately never happened I would add the Indochina intervention [of 1954].”

The United States, Ridgway later said, “could have fought in Indochina. We could have won, if we had been willing to pay the tremendous cost in men and money that such intervention would have required—a cost that in my opinion would have eventually been as great as, or greater than, what we paid in Korea.”

The Road To American Involvement

The U.S. did not intervene directly in the French war. But American support of the French war led directly to the American war in Vietnam. The roots of American involvement in the long and costly Vietnam War go back to the immediate post-World War II years. That’s when the United States decided to underwrite France’s effort to take back its colonies in Indochina—a momentous and fateful decision that flew in the face of this nation’s long-time commitment to human rights and the self-determination of peoples.

That commitment all but dissolved after World War II when the United States found itself in what soon became known as the Cold War against what was perceived as a worldwide communist revolutionary movement led by the Soviet Union. One battleground became the long-time French Indochinese colonies, which the Japanese overran and occupied during World War II.

I n September of 1945, just a few weeks after Japan’s surrender, the nationalist-communist leader Ho Chi Minh (whom the American military had supported during the war in his guerrilla actions against the Japanese) declared Vietnam’s independence from France and mounted a guerrilla war against the French colonial government. In 1947 the Soviet Union resurrected the Communist International, the organization whose goal was to abet communist revolutions around the world. To many in the West it appeared that Ho Chi Minh’s war against the French in Vietnam was part of a Soviet-backed worldwide insurgency aimed at forcefully imposing communism on the world, nation by nation. n September of 1945, just a few weeks after Japan’s surrender, the nationalist-communist leader Ho Chi Minh (whom the American military had supported during the war in his guerrilla actions against the Japanese) declared Vietnam’s independence from France and mounted a guerrilla war against the French colonial government. In 1947 the Soviet Union resurrected the Communist International, the organization whose goal was to abet communist revolutions around the world. To many in the West it appeared that Ho Chi Minh’s war against the French in Vietnam was part of a Soviet-backed worldwide insurgency aimed at forcefully imposing communism on the world, nation by nation.

After the war all of the countries in Eastern and Central Europe came under totalitarian communist rulers. On August 29, 1949, the Soviet Union exploded its first atomic bomb, adding to growing East-West Cold War tensions. Then, in October of that year, Mao Zedong proclaimed the communist People’s Republic of China after winning a long, bloody civil war. By the end of the year Chinese troops had moved to the border of northern Vietnam to provide arms and materiel to Ho Chi Minh’s communist-led Viet Minh.

It was no coincidence that in that fateful year of 1949 the United States shifted from its pro-French but officially “hands off” position in Indochina to one that committed American financial aid, arms and, ultimately, U.S. armed forces to fight communism in the former French Indochinese colonies of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. At the time the colony of Vietnam was nominally headed by French-backed Emperor Bao Dai, who had returned from self-imposed exile that year.

American economic and technical aid flowed into Indochina. By 1952 the U.S. had shipped more than $50 million worth of aid in the form of food, farming equipment, medical supplies, and other non-military supplies to Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos in the first “hearts and minds” effort designed to win the Indochinese people over to American-style democracy.

The first official act that paved the way for American support of the Indochinese colonies was the Mutual Defense Assistance Act of 1949, which was not particularly controversial. It was a continuation of economic aid legislation passed the previous year to help Nationalist China. There was opposition from some fiscal conservatives in Congress about the amount of the expenditure. And some Senators and members of the House expressed concerns that the United States could get too heavily involved in areas not vital to its national interest. But a healthy majority of members of Congress supported the bill’s anticommunist objectives.

The legislation technically applied to the “general area of China.” But the bill, which President Truman signed into law October 6, gave the President authorization to send American military personnel to act as noncombatant advisers to any “agency or nation.” Section 303 of the bill authorized $75 million in U.S. aid for that purpose in the “general area,” which, Secretary of State Dean Acheson told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, could include Indochina.

In addition to the $75 million authorization, the bill more portentously also gave the president authority to send American troops to any “agency or nation” to serve as military advisers. That provision of the Mutual Defense Assistance Act of 1949 had long-range implications for American policy in Vietnam. The law became, as Vietnam War historian William Conrad Gibbons noted, “the basis for the U.S. military advisory mission sent to Vietnam in 1950 by President Truman” and also served “as the authority for all of the other U.S. military missions established in the following years in scores of non-Communist countries.”

The Pentagon Papers put it more bluntly: The act, together with a 1949 NSC policy paper, set American policy in the closing months of the year on a course “to block Communist expansion in Asia.” The Papers said that those two actions provided the paving blocks for “American entry into the Korean War in 1950, the U.S.-instigated formation of the NATO-like Southeast Asia Treaty Organization in 1954, and the progressively deepening U.S. involvement in Vietnam.” The first official American military advisers, known as the Military Assistance and Advisory Group-Indochina (MAAG), arrived in Vietnam in the fall of 1950 to oversee U.S. military assistance to France.

The French were not happy with American aid that went directly to the governments of Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. Gen. Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, the French High Commissioner and Commander in Chief in Vietnam from 1950 until his death (from liver cancer) in 1952, spoke out strongly and directly to Washington to end that aid and get direct American military support. “Proud, sensitive, and highly nationalistic,” de Lattre “ignored the American ‘advisers’ in formulating strategy, denied them any role in training the Vietnamese, and refused even to keep them informed of his current operations and future plans,” George Herring noted.

By June of 1952, with the war in Korea raging and the United States substantially underwriting the cost of the French war, the Minister of Overseas Territories, Jean Letourneau, pressed for even more American aid. Then-Secretary of State Dean Acheson said “it would be wise to end, or threaten to end, aid to Indochina unless an American plan of military and political reform was carried out.”

The French paid lip service to these American demands, and the Truman administration sent an additional $150 million in military aid. The State Department released a communiqué stating the reasons for the support. Indochina was part of the worldwide resistance to “Communist attempts at conquest and subversion,” it said, and France had a “primary role in Indochina” similar to that of the United States in Korea. When Eisenhower took over as President in January of 1953, the United States was paying about a third of the cost of the French war, and Ike and his secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, continued Truman’s policies in Indochina.

Falling Dominoes

On April 7, 1954, a month before the fall of Dien Bien Phu, President Eisenhower held a press conference in Washington. He had decided not to back the French militarily in Vietnam, but nevertheless expressed his concerns about the consequences of a French defeat. In answering a question about the “strategic importance of Indochina to the free world,” Ike said: “First of all, you have the specific value of a locality in its production of materials that the world needs,” such as tin, tungsten, and rubber. “Then you have the possibility that many human beings pass under a dictatorship that is inimical to the free world.”

And “finally,” Ike said, “you have broader considerations that might follow what you would call the ‘falling domino’ principle. You have a row of dominoes set up, you knock over the first one, and what will happen to the last one is the certainty that it will go over very quickly. So you could have a beginning of a disintegration that would have the most profound influences.” Asia, Ike said, “has already lost some 450 million of its peoples to the communist dictatorship [in China], and we simply can’t afford greater losses.” He went on to list the dominoes: “Burma, Thailand, the Malaysian Peninsula, Indonesia, Japan, Formosa, the Philippines and Australia and New Zealand.”

And “finally,” Ike said, “you have broader considerations that might follow what you would call the ‘falling domino’ principle. You have a row of dominoes set up, you knock over the first one, and what will happen to the last one is the certainty that it will go over very quickly. So you could have a beginning of a disintegration that would have the most profound influences.” Asia, Ike said, “has already lost some 450 million of its peoples to the communist dictatorship [in China], and we simply can’t afford greater losses.” He went on to list the dominoes: “Burma, Thailand, the Malaysian Peninsula, Indonesia, Japan, Formosa, the Philippines and Australia and New Zealand.”

This was the first public assertion of the Domino Theory, which would provide the geopolitical unpinning for the Vietnam War policies of Presidents John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Richard M. Nixon. After Dien Bien Phu the United States shaped its Vietnam War policies around the domino principle, backing the noncommunist nationalist leader Ngo Dinh Diem with aid and military advisers in 1954. That support continued under Diem’s successors for the next twenty-one years as the Americans took the lead in what sometimes is called the Second Indochina War against the Vietnamese communists.

Marc Leepson is the long-time senior writer and arts editor for The VVA Veteran. He is also the author of a half-dozen books and the editor of Webster’s New World Dictionary of the Vietnam War.

|

|

|

|