|

|||||||||

|

March/April 2012

BY XANDE ANDERER

On its surface the Rhodesian Bush War that raged from 1964 to 1979 was a simple one: A former British colony was locked in conflict with nationalist (read: communist) guerrillas. But the political situation was far, far more convoluted. The area of southern Africa then known as Rhodesia was first colonized by British and South African settlers in the 1890s. The country was operated as a British colony and was known at different times as South Zambezia, Southern Rhodesia, and the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. But in 1960, when Britain declared its intention to grant independence to its territories in Africa, it also specified a policy of no independence before majority rule. This meant that colonies with a substantial population of white settlers would not receive independence except under conditions of majority rule. The white-minority government in Rhodesia grew fearful of what would happen to the 270,000 white settlers in a nation of 7 million native Africans. As a result, the government declared the country’s independence from British rule on November 11, 1965, in what became known as the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI). With atrocities committed after changes of power in the Belgian Congo and Kenya fresh in their minds, most white Rhodesians (and a sizable number of black Rhodesians) saw their lifestyles jeopardized. Rhodesia was considerably safer and enjoyed a higher standard of living than most African countries. The international community immediately condemned the UDI. The United Nations imposed trade sanctions, and the British Royal Navy enforced a blockade of oil shipments to Rhodesia. The United States stated that “under no circumstances” would it recognize Rhodesian independence. Only Portugal—which was fighting a similar war against nationalist guerrillas in its colony of Mozambique—and South Africa supported independent Rhodesia, and even then never officially. Two rival nationalist organizations emerged: the Soviet-backed Zimbabwe African People’s Union (its armed wing known as ZIPRA) under Joshua Nkomo, and Chinese-sponsored Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANLA), led by Robert Mugabe, along with dozens of splinter groups as infighting and tribal rivalries took their toll. Each group went on to fight its own separate war against Rhodesian security forces, with groups sometimes fighting each other as well. Militants received training in North Korea, Libya, Cuba, and China. When Portugal withdrew from Mozambique in June 1975, Rhodesia found itself on a figurative island, surrounded on three sides by newly minted Marxist regimes in Zambia and Mozambique, and Botswana, which was sympathetic to the nationalists. Hobbled by the British embargo and harsh UN sanctions, the Rhodesian armed forces were forced to rely on military equipment left behind by the British, supplemented with hand-me-downs from their only remaining ally, South Africa. And although the South Africans sent several thousand police units into the fight (the “police” label was used to give plausible deniability to claims that the South Africans were intervening militarily), the Rhodesian military found itself woefully short of boots on the ground. So they did what anyone would do: They posted a want ad.

In the years since, many have suggested that Soldier of Fortune and its controversial publisher, Lt. Col. Robert K. Brown—a former Green Beret who served with the Special Forces in Vietnam—were de facto agents of the Rhodesian government. In fact, Brown had financed the start-up of the magazine with the sale of “overseas employment opportunity packets”—essentially enlistment materials for the armies of Rhodesia and Oman—in other magazines first. Others suggest that the coverage in the magazine had the full blessing of the CIA. Of course, the Rhodesians had other means of finding men eager to fight. Author Dan Guenther, who served as a Lieutenant in the 1st Marine Division in Vietnam from 1968-70, spent the years immediately following the war with other Americans in Australia. “After Vietnam, I lived in Cronulla, Australia, a beachside suburb south of Sydney,” he said. “I hung out with a group of Americans at the Hotel Cecil. There was a good network of American expatriates there. We shot pool, drank beer, and watched all the bikinied Aussie girls.” Guenther remembers Rhodesian Army recruiters coming to town in search of veterans fresh from the jungles of Indochina. “I remember a man representing Maj. Lamprecht, a Rhodesian Army contact officer, looking for veterans living in Sydney,” Guenther recalled. “A couple Aussies I knew talked to him but declined to pursue it. There was no money in it.” Guenther’s experiences with other Vietnam veterans in Australia—and their recruitment for Angola, Rhodesia, and private security firms in South Africa—play prominently in his novel, Glossy Black Cockatoos.

The Rhodesians managed to recruit about 1,400 foreign nationals for their cause. Volunteers came from across the globe: Britain, Ireland, South Africa, Portugal, Hong Kong, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. But the Americans were held in particularly high regard due to their recent Vietnam War experience. It is believed that some three hundred Americans served in the Rhodesian Light Infantry during the course of the conflict. Most were Vietnam veterans. Each had his own reasons for joining the fight. The military was “a job that carried a lot of respect,” said Richard Nelson. “It was man’s work; for men who were tough, trustworthy, and able to work as a team.” Feeling he’d made the most of his tour in Vietnam, Nelson decided to return home to pursue a career in medicine when his enlistment ended in 1973. For the next four years he worked toward his undergraduate degree in pre-med, maintaining an A- average. But when his GI Bill money ran out, Nelson began to second-guess his chances of completing medical school. Enticed by letters from an Army buddy in Rhodesia, he began to consider returning to the soldier’s life. “In today’s world, many people see professional soldiers as possibly violent or sadistic people,” he said. “But it’s just like any other professional job. I had years of military training and a wealth of combat experience. I really thought I could help there.” Although the $1,000 a month he would receive for his service was a definite enticement, Nelson says he headed for Africa because he believed in the cause. “A lot of time has passed, and the world has changed a lot. History has oversimplified the fighting there as blacks versus whites. It was not. It was more complicated than that,” he said. “Only 10 percent of the people—black and white—supported the terrorists, who were communist-supplied and communist-financed.” In fact, the 10,000-man Rhodesian Army was composed of both white and black Rhodesians. While some units, such as the Rhodesian SAS and the Rhodesian Light Infantry, were all-white, most units of the Rhodesian military were mixed. And by 1978 black soldiers comprised the majority of its ranks. “These were terrorists—revolutionaries—we were fighting,” Nelson said. “ZIPRA shot down two civilian airliners. ZANLA slaughtered innocent people in raids on their farms.” Donald Bachman—not his real name—who was twice wounded while serving with the Marines at Khe Sanh from 1967-68, saw it the same way: “You have to see things in terms of the world at that time,” he said. “The U.S. had left Vietnam, and it fell to the communists. Then Laos and Cambodia went. We didn’t have the benefit of knowing how things were going to turn out. I had never even heard the term ‘apartheid’—no one had. Here was another country under attack by communist guerrillas.” Having been raised on a steady dose of the Domino Theory, Bachman chose to go where he thought he could best help stem the tide of communism. “The communists—ZANLA and ZIPRA—fought the exact same way as the Viet Cong,” he said. “They were trained by the Chinese and the Cubans. And in many ways they were much better supplied than the VC.” Who better to fight these guerillas than someone who had seen it before in Vietnam? “We Americans knew the tactics,” Bachman said. “We knew bush fighting. We could stand the heat—literally and figuratively.” Most Americans who fought in the Rhodesian Bush War bristle at the term “mercenary.” “Contrary to how we were labeled in the papers, we were not mercenaries. We were sworn into the Rhodesian Army the same as any of their men,” Bachman said. “We served under the same rules and were paid the same as the regulars. We wore the exact same uniform. Time magazine once called the Rhodesian Army ‘the world’s best fighting unit.’ I’m proud of that. I was a soldier. Historians can debate the other stuff.” Mike Kelso sees it a little differently. Too young to fight in Vietnam, the 17-year-old enlisted in the Army in 1973 and was assigned to the 82nd Airborne. Itching for action, he grew frustrated with the banal routines of the peacetime Army. “People can call me a mercenary,” he said. “That’s fine. I’m okay with that. I did what I had wanted to do since I was a little boy—be a professional soldier. Going to war was just business.” After his discharge from the Army, Kelso wrote to the address at the bottom of that very first ad in Soldier of Fortune. Six weeks later he received a contract in the mail and reported for duty in 1977. He spent fifteen months fighting insurgents with the Rhodesian Light Infantry, including six combat jumps. “And there wasn’t any jump pay for it, either,” he said. “That was just the way we did it.” Unlike some of his peers who seem only able to speak of the combat, Kelso is more reflective about his time on the dark continent. “Just being there in Africa was incredible,” he recalled. “It was like living inside the pages of National Geographic.” But by 1979 Kelso could read the writing on the wall. “The war was lost. Everyone knew it,” he said. “I went home on leave and never went back. “It’s one thing,” he said, “for a professional soldier to risk his life and lose it in support of his own country, but when the battle is clearly lost and all hope is gone, well... We fought the good fight, did what they asked us to do. But when it became obvious the war was lost, dying didn’t make much sense.”

Moderate Bishop Abel Muzorewa became the new country’s prime minister, but guerrilla leaders Nkomo and Mugabe rejected the Muzorewa government as a puppet regime and resumed their attacks. The reinvented nation, with its open elections, had hoped to gain international recognition, but neither the British nor the Americans moved to do so. Despite having officially labeled ZANLA and ZIPRA leaders as “terrorists,” the British government, under newly elected Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, organized a peace conference in London in August 1979 to which all nationalist leaders were invited. Mugabe and Nkomo agreed to end the war in exchange for new elections in which they could participate. In exchange, all economic sanctions were lifted and British rule resumed briefly under a transitional arrangement leading to full independence. A formal cease-fire took effect on December 21, 1979. The war had raged for fourteen violent years and cost 30,000 lives, including seven Americans. A contentious election, rife with accusations of fraud and voter intimidation, took place on March 4, 1980, resulting in a victory for Mugabe, who assumed the position of prime minister. On April 18, 1980, the new nation of Zimbabwe gained full independence and international recognition. Mugabe has remained in power since. As for Richard Nelson, he fell in love with a Rhodesian woman during the war and elected to stay behind in the brand-new nation. “The way I saw it, I didn’t fight on a losing side. I helped forge that new country,” he said. “I wasn’t intimidated by the idea of black-majority rule. I fought alongside them, on their behalf, really. They were citizens of old Rhodesia, too, and much of the terrorists’ violence was directed toward them as well.” Together, Nelson and his wife ran a rural medical clinic for nearly twelve years before health issues, combined with Zimbabwe’s dismal economy, forced them to join other white Rhodesians in Texas. Despite all that has happened in the intervening years, Nelson says he is still proud of his service. “I was doing a job, and I knew the consequences,” he said. “I have no regrets.”

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

|||||||||

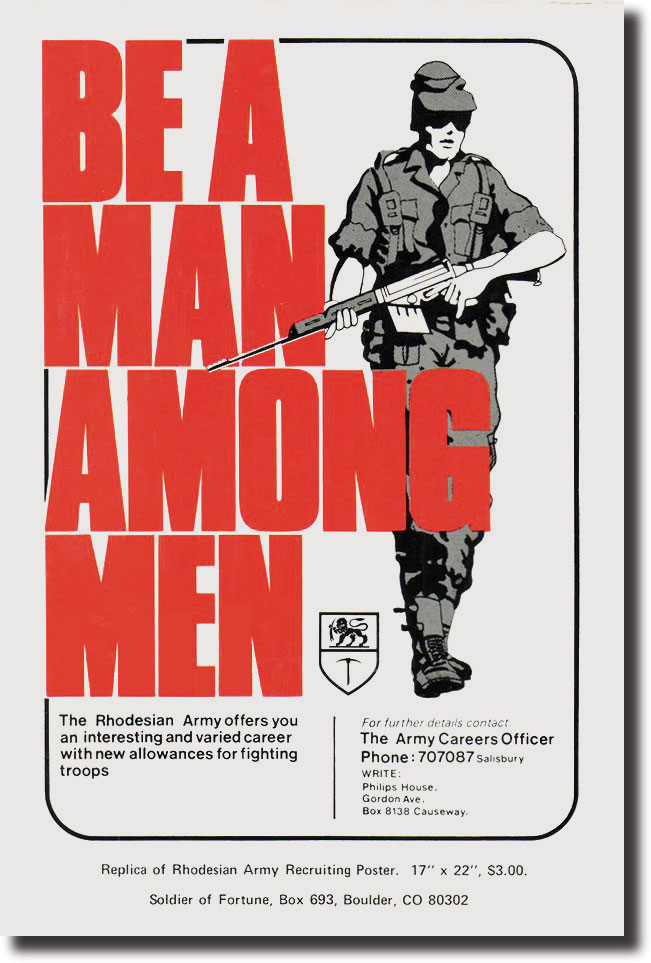

From its very first issue in 1975, Soldier of Fortune magazine featured advertisements seeking “men among men” for “interesting and varied careers as fighting men in Rhodesia.” The full-page, color ads were featured in prime locations, usually on the back cover. Soon articles about the struggles against the communist insurgencies in Rhodesia and Angola began to dominate the magazine.

From its very first issue in 1975, Soldier of Fortune magazine featured advertisements seeking “men among men” for “interesting and varied careers as fighting men in Rhodesia.” The full-page, color ads were featured in prime locations, usually on the back cover. Soon articles about the struggles against the communist insurgencies in Rhodesia and Angola began to dominate the magazine.

Highly successful campaigns against the insurgents, including air mobile strikes and the bombing of rebel camps by the air force, continued through 1979. However, as the combined forces of ZIPRA and ZANLA reached 12,500 guerrillas, it became evident that the insurgents were entering the country faster than the Rhodesian forces could kill or capture them. An additional 38,000 fighters remained in reserve across the border in Mozambique and Zambia, massing for what appeared to be a more conventional invasion. The Rhodesian government realized any hope of survival lay in negotiating an internal political settlement with moderate factions within Rhodesia. As it was for the Americans in Vietnam, the Rhodesian military won virtually every battle they fought against the guerrilla armies, yet they lost the war. A settlement was forged on April 24, 1979, creating the newly minted nation of Zimbabwe-Rhodesia.

Highly successful campaigns against the insurgents, including air mobile strikes and the bombing of rebel camps by the air force, continued through 1979. However, as the combined forces of ZIPRA and ZANLA reached 12,500 guerrillas, it became evident that the insurgents were entering the country faster than the Rhodesian forces could kill or capture them. An additional 38,000 fighters remained in reserve across the border in Mozambique and Zambia, massing for what appeared to be a more conventional invasion. The Rhodesian government realized any hope of survival lay in negotiating an internal political settlement with moderate factions within Rhodesia. As it was for the Americans in Vietnam, the Rhodesian military won virtually every battle they fought against the guerrilla armies, yet they lost the war. A settlement was forged on April 24, 1979, creating the newly minted nation of Zimbabwe-Rhodesia.