|

||||||||||||

|

November/December 2014

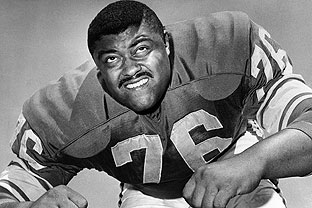

And the 6-foot, 5-inch, 300-pounder has devoured every experience that world has brought his way. Although best known for his prowess on the football field—most famously as a member of the Fearsome Foursome, the Los Angeles Rams’ vaunted defensive line of the 1960s—Grier’s life has been culturally ubiquitous. From his hardscrabble upbringing as one of twelve children in rural Georgia, to collegiate All-American at Penn State, to All-Pro with the New York Giants and the Rams, to entertainer, activist, political confidante, author, and mentor of inner-city youth, Grier will tell you the one thing he has refused to do has been to follow any preordained life path. Name a cultural pulse point of the last fifty years, and there’s a good chance Grier was involved: The greatest game in NFL history? That would be the 1958 NFL championship between the Giants and the Baltimore Colts. Grier was there, locked up on the battered goal line the Colts’ Alan Ameche crashed through in overtime to win the game. The assassination of Robert F. Kennedy? Grier—who was escorting Kennedy’s pregnant wife, Ethel—wrestled Sirhan Sirhan to the ground. The Civil Rights Movement: Check. Talk show host: You know it. The landmark television miniseries Roots? That’s Grier playing Big Slew Johnson. Don’t forget appearances on ’70s staples such as Kojak, Quincy, and CHiPs. The Trial of the Century? Grier visited O.J. Simpson in prison for prayer and counseling as he awaited trial. And perhaps the greatest indication of his continuing relevance: an appearance on a 1999 episode of

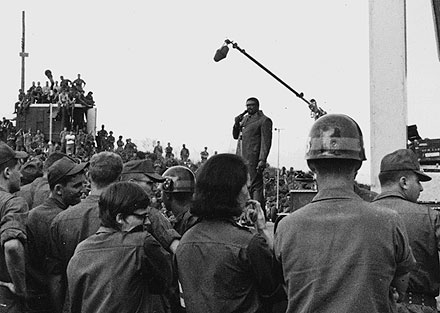

On December 14, 1968, the famously nervous flier found himself standing beside Bob Hope on the tarmac at LAX awaiting a flight bound for Vietnam. “I’d signed with a booking agency in 1959 and began to travel the R&B concert circuit during [football] off-seasons,” Grier explained. “They called me the ‘300-pound Perry Como.’ I sang, played a little guitar, and was even the master of ceremonies at many of the concerts.” More than a novelty act, Grier went on to make about seventy television guest appearances. He also cut twenty-five records, including 1964’s “Soul City.” Grier wrote more than twenty songs in that span. “I had known Bob Hope from a bunch of television appearances I’d made.” Grier said. “And he had just heard me sing at a show at the Los Angeles Coliseum. Afterward he asked me to come with him on his USO Christmas show.” As part of “Operation Holly,” Hope’s 1968 tour, Grier performed for personnel at the U.S. bases at Long Binh, Cam Ranh Bay, Da Nang, Chu Lai, and Phu Cat, as well as aboard the carriers U.S.S. Hancock and New Jersey, and at Korat and U-Tapao in Thailand, along with stops in Korea and Guam. The trip left Grier with a wealth of memories. “I’d just arrived in Vietnam—I mean, right off the plane. I hopped in a jeep: guy in camouflage driving, guy in camouflage on the machine gun in the back. I look down and I’m wearing a bright yellow shirt. Talk about a big target.” Grier will never forget the reception Hope and the troupe received: “Everyone came out to see us. The hills around the stage were coated with green from all the soldiers sitting out there. “Every show we did, I followed Ann-Margret. As you can imagine, the boys were crazy about her. Not as much once I took the stage,” he chuckled. “But my style was different. We weren’t competition. I sang a soulful song called ‘Bad News.’ It was wonderful the way the troops responded. But I never want to follow Ann-Margret again.”

The performers played to packed houses at every stop. Gen. Creighton Abrams joined the troupe on stage at Long Binh; Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker was in the audience at one show. “I was a huge hit in Thailand. Not too many 6-foot-5-inch black men in Thailand.” Grier recalls the King of Thailand sitting in with the band at one of the tour’s two stops in that country. The tension of being in an active war zone was never far from the entertainers’ minds. Hope had been entertaining the troops for twenty-five years and seemed the definition of unflappable. “In the middle of one of the shows there was this incredible noise. Rockets started coming in. Bob says calmly, ‘This is one time the show must not go on.’ The audience scattered and so did we,” Grier said. “At first we crouched in foxholes. Then someone shouted for us to run for the helicopters, but I ended up in one of those combat helicopters instead of the bigger helicopters we arrived on. Next thing we knew, we were turning and diving and firing. I saw the streaks flying up from the ground at us and asked the pilot what they were. “‘Just tracers,’ he said. But what he didn’t know was I’d been in the Army. I knew there were real bullets in between those tracers.” Grier related easily with the troops. He’d been drafted into the Army in 1957 after one of his best seasons in the NFL. “The Giants had just won the NFL championship game, beating the Chicago Bears 47-7, and I’d been picked to play in the Pro Bowl in Los Angeles that year,” he said. “The day I left for that game I received that letter we all know.” Grier would miss the 1957 NFL season while serving eighteen months at Ft. Dix. “I had no objections to our system, and I believed I had a duty to perform as a citizen of the country I love. But I couldn’t help but be a little disappointed. I’d just gotten to the level where I could renegotiate my salary with the Giants for a little bit more pay.” All in all, Grier said, “the rigors of Army life suited me: getting up early, the exercise, learning to make my bed the way the Army told me. As near as I could tell, I was not given any special treatment—good or bad. And best of all, the food was plentiful.” In Vietnam the USO troupe visited hospital wards and spoke with personnel. He remembers most clearly those with the most horrific injuries. “I saw more seriously wounded men, women, and even children than I care to remember.”

As he listened to those men, Grier “questioned why we were fighting such a ‘limited war.’ As a football player, I knew what that could lead to. When I was with the Giants, we had an expression: ‘Playing for nickels.’ I don’t know where it came from, but it meant playing with serious determination. “That is the only way to play to win, both on the playing field and over there. Oftentimes in scrimmage—because we weren’t playing for nickels—players would get careless, and morale would drop. When we played for nickels—all out like that—there were actually fewer injuries.”

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

||||||||||||

It really is Rosey Grier’s world. The rest of us simply live in it.

It really is Rosey Grier’s world. The rest of us simply live in it.

The injustice was not lost on him. “To have been through the things they were enduring—and then to be treated as if they had committed some crime. That’s our bad.”

The injustice was not lost on him. “To have been through the things they were enduring—and then to be treated as if they had committed some crime. That’s our bad.”