|

|||||||||

|

March/April 2014 Toxic Hitchhikers BY CLAUDIA GARY

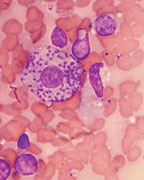

Veterans of all wars must contend with exotic parasites. These insidious stowaways find human hosts through soil, water, food, or airborne “vectors”—insects such as mosquitoes and sand flies. Although the parasites may be hidden, they can be detected. In some cases, once they are, a cure can be quick and uncomplicated. In other cases, treatment takes time. In still others, the years without detection can create a tragedy. Parasitic infections are one focus of Tropical Medicine (also called Travel Medicine), an Infectious Disease subspecialty with a history intertwined with war and colonization. Some of these infections—such as leishmaniasis, lymphatic filariasis, schistosomiasis, and soil-transmitted helminth infections—are termed “neglected tropical diseases.” Dr. Daniel S. Caplivski, director of the Travel Medicine program at New York’s Mount Sinai Medical Center, explained that the “neglected” status of many parasitic infections is largely a result of history and economics. “There was a certain amount of investment in treatment and cures when British colonials were getting sick,” Caplivski said. “That’s where Tropical Medicine was born, and that’s where a lot of our knowledge came from. Over the last one hundred years we’ve had limited advances in research and treatment.” Two of the most devastating and lasting parasitic infections Vietnam veterans have suffered are those caused by mosquito-borne filarial worms and by foodborne liver flukes (Opisthorchis viverrini). Lymphatic filariasis, while generally not fatal, can be disfiguring and debilitating. Liver fluke infection, on the other hand, can go virtually undetected for decades and then cause a deadly cancer, cholangiocarcinoma. According to the VA’s Veterans Health Initiative, veterans who have returned from Iraq may be at risk of sand fly fever, malaria, amoebic dysentery, giardiasis, and leishmaniasis. Those who have returned from Afghanistan are at risk of protozoan parasites Entamoeba histolytica and Giardia lamblia, as well as soil-transmitted helminths. Intestinal parasites are prevalent in Iraq. It is always important to tell your doctor where you served when seeking treatment of any skin or intestinal disease. In some cases, the less obvious parasitic infections have a potential to do more damage. What follows is a brief catalog. Amebiasis (Entamoeba histolytica) “When amoeba go to the brain, headache, fevers, and stroke-like symptoms are common. A brain abscess is a more focal aspect of the brain, and will affect a specific area of function, such as controlling your arm.” Diagnosis is fairly simple using a stool test or a blood test. However, it can be challenging to determine if someone has a liver abscess, for example, from amoeba or from just regular bacteria from their lung or gut. Ascariasis (Ascaris) Helminths Lymphatic Filariasis (Filarioidea) “The problem is that we don’t have a very good treatment for it. The treatment is merely to prevent transmission to other people. Adult nematodes live in the lymph system, usually for about seven years, and then they die by themselves. But the damage has already been done, because they leave behind a lot of scarring in the lymph system. The patients are left with damaged lymph nodes and lymph drainage system, so the swelling doesn’t go away.” While there is not a good surgical option at present, treatment for this lymphedema consists of “physical therapy, where they try to localize the swelling with massage, massaging the fluid out of the spaces—the interstitium—and back into the blood vessels.” This disease, Caplivski said, is one that is “on the brink of eradication, if we could just treat every last person to prevent them from spreading it to other people via mosquitoes.” It can be misdiagnosed, he cautioned, “because the tests for it are difficult. If we’re trying to catch the parasites in the bloodstream—the baby parasites—we ideally take a blood test at night. That’s because the parasites tend to release their young at night. They coevolved with the mosquitoes, which are nighttime feeders.” Leishmaniasis (Leishmania) The troops treated at Walter Reed have undergone intravenous therapy with a drug called pentavalent antimony. Not readily available in pharmacies, the therapy is supplied by the CDC parasitic drug service. The 20-28-day intravenous treatment is inconvenient. Alternatives, including a fungicide called amphotericin, have been used with some success. Schistosomiasis (Schistosoma haematobium) Strongyloidiasis

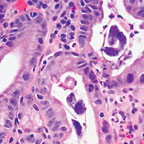

Opisthorchis viverrini is a parasitic liver fluke that sometimes leads to bile duct cancer. “It is contracted by eating undercooked fish in Southeast Asia,” Brindley said. “The locals eat freshwater fish that live in the lakes and rivers that drain into the Mekong River. The fish are often infected with this parasite, and if people eat that fish, they are likely to become infected. Many of the local people eat dishes where the fish is prepared in such a manner that the disease survives, so people eat it and become infected. Soldiers, too, can become infected through eating undercooked or raw fish. “It’s a rather unusual infection,” Brindley added, “because it also causes cancer. Not many infectious diseases cause cancer, and it is very unusual for a worm infection—a parasite—to cause cancer. The reason is because of where it lives. The worm is ingested with this fish, and becomes active in the small intestine. It migrates out of the intestine into the biliary tree, the system that pumps bile from the liver into the gut. “What is unusual is that the worm crawls up into that area. It’s normally a sterile area inside the liver, and most organisms would not find it a very physiologically attractive place to live, compared to, say, the gut. But the liver fluke crawls up there. They are not very big—they’re just under an inch—and are flat, leaf-shaped things that can live for months or years. “When the parasite is there, it causes an immunological and an inflammatory reaction,” Brindley said. “There is a kind of chronic wound that forms around where these worms are. The worms are doing their own thing, causing more discomfort to the microenvironment; they lay eggs that get trapped in the tissue. The bile ducts become inflamed and fibrotic. That’s called cholangitis, an inflammatory disease of the biliary system. “At a lower level, it might be asymptomatic. And then, very strangely—it probably takes years, decades—some of the cells that line the bile duct undergo a neoplastic transformation. They become cancerous, probably because they are living in this chronically inflamed condition. Probably what happens to the nuclei of those cells is that the DNA is damaged by some of the immunoreactive chemicals and a change occurs. “DNA-damaged cells start to grow out as a tumor. The lining of the bile duct can start to grow as a tumor and spread. At that point it actually becomes a kind of liver cancer, with a dismal prognosis. Because by the time it’s diagnosed, it’s usually advanced, and the person now is jaundiced.” Local people suffer very high rates of this cancer, probably the highest in the world. Yet the initial infection is easily treated by taking a safe anti-worm drug called praziquantel by mouth. Unfortunately, they will be reinfected if they continue to eat undercooked fish. But someone who took the medication and did not go back to that area and did not eat any more undercooked fish has a 90-100 percent chance of being cured. “If a soldier left that region, he would not get infected back in the U.S.,” Brindley said. “He may have the infection at a low level, so it’s asymptomatic. It is long lived. You might have some discomfort, but most people at a low level of infection wouldn’t even feel symptoms of the parasite. Still, just having the parasite is strongly associated with the development of this liver cancer. And if they did have liver cancer in this particular form, cholangiocarcinoma, it’s likely they had been infected.” Anyone who has been “out in the jungle on special ops or otherwise eating raw fish occasionally in that part of the world, would definitely want to have a doctor or nurse test for liver flukes,” Brindley said. “It wouldn’t be too hard for the VA to organize a test to check that.” The CDC has a parasite diagnosis service on its website.

Parasites are unpleasant, hard to face, and sometimes hard to find. Sometimes the cure is easy and complete, sometimes not. But the worst outcome usually comes from misdiagnosis, delayed diagnosis, or nondiagnosis. That’s why it’s essential to find out whether any of these parasites left the war zone with you. If your service history shows that you have risk factors, tell your physician you need a test. Don’t take no for an answer. Despite Tropical Medicine’s importance to the military, its specialists are not always readily available to veterans. There are several good sources of information, however. One is the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. Other helpful organizations include the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research; the Department of Veterans Affairs, which, through its Veterans Health Initiative, runs an independent-study-based continuing medical education program that includes a course in Endemic Infectious Diseases of Southeast Asia; and the Public Library of Science Neglected Tropical Diseases. Centers for Disease Control has information on neglected parasitic infections, neglected tropical diseases, liver flukes, and strongyloidiasis.

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

|||||||||

“Leishmania, a parasite transmitted by the bite of the sand fly, has been a problem in particular for veterans of wars in the Middle East, in Iraq, and Afghanistan,” Caplivski said. “It’s a protozoan parasite, which means it’s not visible except under the microscope. A typical symptom of leishmaniasis is a skin ulcer. These were nicknamed ‘Baghdad boils.’ The ulcer on the skin can be misdiagnosed as a bacterial infection. The antibiotics that are useful for bacterial infections are not effective against this particular parasite.”

“Leishmania, a parasite transmitted by the bite of the sand fly, has been a problem in particular for veterans of wars in the Middle East, in Iraq, and Afghanistan,” Caplivski said. “It’s a protozoan parasite, which means it’s not visible except under the microscope. A typical symptom of leishmaniasis is a skin ulcer. These were nicknamed ‘Baghdad boils.’ The ulcer on the skin can be misdiagnosed as a bacterial infection. The antibiotics that are useful for bacterial infections are not effective against this particular parasite.” Schistosomiasis is a waterborne parasitic infection that can lead to urinary tract problems. According to the VHI, it is “found in Iraq, but infection is thought to be infrequent. Schistosoma haematobium, which causes urinary schistosomiasis, is the only species of the parasite that has been reported in Iraq. Western military personnel are not at risk of schistosomiasis unless they wade or swim in infested water. Schistosomiasis is not reported in Afghanistan.”

Schistosomiasis is a waterborne parasitic infection that can lead to urinary tract problems. According to the VHI, it is “found in Iraq, but infection is thought to be infrequent. Schistosoma haematobium, which causes urinary schistosomiasis, is the only species of the parasite that has been reported in Iraq. Western military personnel are not at risk of schistosomiasis unless they wade or swim in infested water. Schistosomiasis is not reported in Afghanistan.” Strongyloidiasis infects people directly, without a vector. According to Paul J. Brindley, Ph.D., a professor of Microbiology, Immunology, and Tropical Medicine at the George Washington University Medical Center, “The worm passes out with the host’s stool, and in conditions where sanitation is not optimal, the parasite can grow in the environment and be transmitted if another person then comes in contact with contaminated soil, or even inside a room. It’s a problem in all western countries in institutional settings—prisons and so forth—where the walls or other areas may be contaminated with human waste.”

Strongyloidiasis infects people directly, without a vector. According to Paul J. Brindley, Ph.D., a professor of Microbiology, Immunology, and Tropical Medicine at the George Washington University Medical Center, “The worm passes out with the host’s stool, and in conditions where sanitation is not optimal, the parasite can grow in the environment and be transmitted if another person then comes in contact with contaminated soil, or even inside a room. It’s a problem in all western countries in institutional settings—prisons and so forth—where the walls or other areas may be contaminated with human waste.”