|

|||||||||

|

March/April 2014

BY MARC LEEPSON

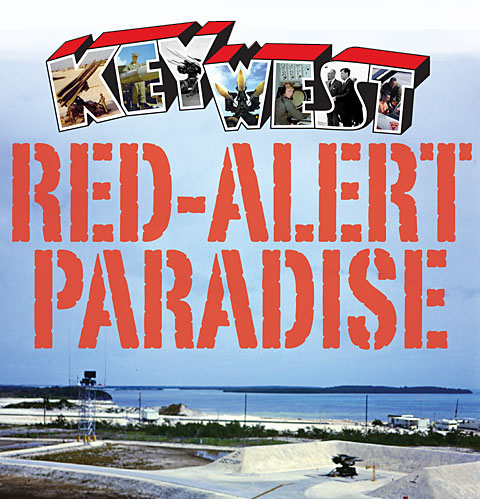

In October of 1962 the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union nearly went nuclear during the Cuban Missile Crisis. The American military stood on high alert the night of October 22 as President John F. Kennedy gave a somber eighteen-minute television address from the White House. Looking grim and resolute, JFK warned that the Soviet Union was preparing to set up “offensive missile sites” on the island of Cuba less than a hundred miles off the coast of Key West, Florida. The purpose of the sites, he said, “can be none other than to provide a nuclear strike capability against the Western Hemisphere.” The “secret, swift, extraordinary buildup of communist missiles,” Kennedy said, amounted to “a definite threat to peace” on the part of the Soviets as well as a “deliberatively provocative and unjustified change in the status quo which cannot be accepted by this country.” If the Soviets launched any missiles from Cuba against “any nation in the Western Hemisphere,” the President said, it would be considered an attack “on the United States requiring a full retaliatory response.” The entire world, he said, stood at “the abyss of destruction.” Kennedy called on the Russians to remove the missiles and announced he was setting up a naval blockade of Cuba, ringing the island with U.S. Navy ships. If the Soviets tried to bring in more missiles, action would be taken. Tensions rose as a small flotilla of Soviet ships steamed toward Cuba. U.S. military forces around the world immediately went to DEFCON 3, two steps above normal, for the first time in U.S. history. The Strategic Air Command ordered B-52 bombers in the air around the clock and readied some 350 other nuclear-armed bombers and other aircraft. On October 24 the Soviet cargo ships reversed course. But the crisis did not end. Things heated up again three days later when a Soviet surface-to-air missile shot down an Air Force U-2 over Cuba, killing the pilot, Maj. Rudolf Anderson. The next day, October 28, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev announced he would remove the missiles from Cuba. The immediate crisis ended.

But things remained tense in Key West, that southernmost American city sitting at the end of a 150-mile-long string of tropical islands. Two days before Kennedy’s speech, orders went out to the 6th Battalion, 65th Artillery, a HAWK missile unit at Fort Meade in Maryland, to move ASAP to Key West.

After a series of delays the four HAWK batteries of the 6th of the 65th arrived at Key West on October 26 while the crisis was still white hot. The question was where to put the batteries—and the hundreds of Army personnel who went with them. The answer: The Army plopped the missiles on Key West’s Atlantic-facing public beach. The troops set up machine-gun emplacements, dug fox holes, and strung triple-strand barbed wire between the sidewalk and the beach. The men were billeted in the seedy, recently boarded-up Casa Marina Hotel, a once-fashionable Victorian edifice a block from the beach.

Later, the sites were named in honor of Key West residents who died in the Vietnam War: Army CPT Eckwood H. Solomon, Jr., Army PFC Richard A. Recupero, Army SPEC4 Florentino R. Roque, and Army MAJ Peter S. Knight. On November 26 President Kennedy flew to Boca Chica aboard Air Force One to inspect the troops and boost morale. In his remarks to the troops JFK described the Cuban Missile Crisis as “the most dangerous days that America has faced since the end of World War II.” He then went on to inspect the HAWK anti-aircraft missile sites.

The four HAWK batteries would remain in Key West until June of 1979 when all operations ceased and the unit moved to Fort Bliss, Texas. During those years, not one missile was fired. Each battery, though, did conduct live-fire exercises. To do so, they moved temporarily to White Sands Missile Range in southern New Mexico near Fort Bliss. The reason: In order to test them, the missiles had to be locked onto something flying. At White Sands the targets were drones. It would have been too dangerous with all the military and civilian air traffic around Key West to do the testing there. Plus, the debris from the resulting explosions would have crashed onto densely populated Key West. Air space was cleared around White Sands during the live firing tests, and there was no danger that falling debris would hit anything but the empty desert that makes up the 3,200-square-mile missile range.

Yes, there was “SCUBA diving, fishing, and going after girls,” said Jerry Rhyne, who put in two tours with the HAWK missile batteries in Key West from 1969-73. But when on duty the men had to respond immediately, twenty-four hours a day, to any perceived threat. “We pulled a lot of thirty-six-hour shifts,” he said. “We were always getting alerted that something was going on.” When radar picked up something suspicious, “we hot-footed it to our positions,” Rhyne said. Several times during his tenure “we picked up planes flying out of Cuba right on the water, something that NORAD couldn’t find. Once a Cuban defector came in with his MIG.” “You never knew if Cubans with Russian missiles would send out ships toward the U.S.,” said Tom Hambright, a U.S. Navy Vietnam veteran who came to Key West in 1968 and today is the Monroe County, Florida, historian. The HAWK battery personnel “never knew if the Russians were going to shoot the missiles. If they did, you were dead. You were always in that pattern. We had to be prepared to fight.” U.S. radar planes were “flying twenty-four/seven in the 1970s,” Hambright said. “But radar couldn’t see the low-flyers, so one HAWK battery was always hot. At the same time we had two F-4s sitting on the runway with the cockpits open ready to go. Sometimes they kept their engines running.”

Key West, where the average daily temperature is 77 degrees, had a population of around 35,000 in the mid sixties. It “was a sleepy little Navy town back then,” Jerry Rhyne said. The town had three Navy facilities: Boca Chica Air Station, the Seaplane Base, and the Key West Naval Base. About a third of Key West’s population consisted of military personnel. “There were no tourists, but a lot of hippies,” said Rhyne, who commanded Charlie Battery during his second tour. “It was mostly hippies and military people.” The Navy remains in Key West today, but the city is no longer a sleepy place. With its warm climate and laid-back atmosphere, Key West today is one of the most popular tourist attractions in the nation. More than a million people visit every year. It’s a safe bet that few notice what’s left of the HAWK missile batteries. The Alpha Battery site has been enveloped by the Army Special Forces underwater operations school. Just about all that’s left of Bravo Battery by the airport is a half-dismantled radar tower. The old Delta Battery site is now the home of a National Weather Service Doppler radar station. Charlie Battery sits long abandoned behind a locked, chain-link fence near Geiger Key just north of the Navy base at Boca Chica. The radar towers still stand, skeletal reminders of the past. The ready building and the other structures are crumbling, covered with graffiti and surrounded by overgrown weeds. “Nobody knows it’s there,” one long-time Boca Chica civilian employee said recently of the remains of C Battery. “I didn’t know about the HAWK batteries until I came to Key West,” said Navy LT Keith Giacopuzzi, an F-5 pilot currently stationed at the Navy Air Station. “I assumed there were military defensive systems at Key West due to its proximity to Cuba, but I didn’t know any specifics. After moving here, I found out about them. We fly over Charlie and Delta batteries almost every day. But I don’t know any details other than the fact there were HAWK missiles stationed here. “I don’t think I have ever heard the HAWK batteries mentioned at the squadron and wouldn’t be surprised if most of the members of the squadron had no knowledge of them.”

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

|||||||||

The HAWK (Homing All the Way Killer) medium-range surface-to-air missile system had been developed by Raytheon in the mid-fifties; the Army deployed its first HAWK batteries in 1960. HAWK missile batteries eventually would be set up in South Korea, Germany, Okinawa, the Panama Canal Zone, and in Vietnam north of Da Nang and at Tan San Nhut, Long Binh, Binh Hoa, and Chu Lai.

The HAWK (Homing All the Way Killer) medium-range surface-to-air missile system had been developed by Raytheon in the mid-fifties; the Army deployed its first HAWK batteries in 1960. HAWK missile batteries eventually would be set up in South Korea, Germany, Okinawa, the Panama Canal Zone, and in Vietnam north of Da Nang and at Tan San Nhut, Long Binh, Binh Hoa, and Chu Lai.  Soon thereafter the batteries moved onto four new facilities spread out around the city. Each battery had two firing sections. Each section consisted of three separate launchers that held three HAWKs. In addition to those eighteen missiles sitting ready to fire, each battery had an additional eight armed and ready HAWKs to replace them. Each site also had five radar towers and an array of outbuildings. Two of the sites were near the airport and two were on the outskirts of the Key West Naval Air Station on Boca Chica Key, a few miles north of town.

Soon thereafter the batteries moved onto four new facilities spread out around the city. Each battery had two firing sections. Each section consisted of three separate launchers that held three HAWKs. In addition to those eighteen missiles sitting ready to fire, each battery had an additional eight armed and ready HAWKs to replace them. Each site also had five radar towers and an array of outbuildings. Two of the sites were near the airport and two were on the outskirts of the Key West Naval Air Station on Boca Chica Key, a few miles north of town.

They may not have fired a missile in anger, but during the seventeen Cold War years that the HAWK batteries were in Key West hundreds of Army air defense personnel put in long shifts, ready at all times day and night to fire at invading missiles and aircraft. More than a few times things got tense.

They may not have fired a missile in anger, but during the seventeen Cold War years that the HAWK batteries were in Key West hundreds of Army air defense personnel put in long shifts, ready at all times day and night to fire at invading missiles and aircraft. More than a few times things got tense.