|

|||||||||

|

January/February 2014

Linebacker II: The Christmas Bombing BY EARL H. TILFORD

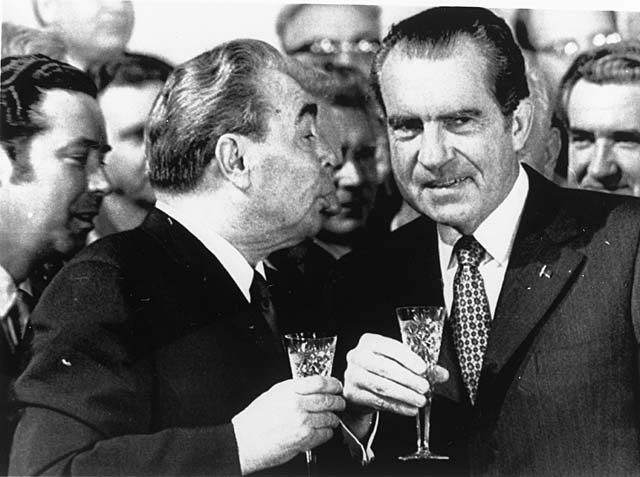

President Richard M. Nixon’s national security advisor, Henry A. Kissinger, believed the depleted will of the American people would not support the commitment of forces at levels needed for victory. He also feared the loss of credibility likely to result from a precipitous withdrawal. As a member of the realpolitik school of international relations, Kissinger also believed that the willingness to use military power leveraged diplomacy. Kissinger’s diplomacy turned on opening the door to China and exploiting the Sino-Soviet split. In February 1972 President Nixon made a state visit to China. In May, as he renewed the bombing of North Vietnam, Nixon was in Moscow negotiating the first treaty limiting the rate of expansion of U.S. and Soviet nuclear arsenals—a critical matter considering the Russians had gained rough nuclear parity while America’s military was bogged down in Vietnam. For the two superpowers the conflict in Vietnam had become an anachronism within the larger Cold War. Sensing strategic urgency and thinking election-year political concerns might restrain Nixon’s response, Hanoi launched a massive invasion of South Vietnam on March 31, 1972. On May 10 Nixon ordered Operation Linebacker (later dubbed “Linebacker I”), arguably the most effective use of air power in the Vietnam War, one in which precision-guided munitions played a key role. Linebacker I proved effective because the strategy countered North Vietnam’s invasion force of fourteen divisions of the Peoples’ Army of Vietnam (NVA). Additionally, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), benefiting from massive infusions of U.S. weapons—along with improved training and tactical leadership—fought well enough. American air power provided the ARVN with massive close air support while also attacking North Vietnam’s transportation system and vital military targets. During the six months of Linebacker I (May 10-October 23) 155,548 tons of bombs fell on North Vietnam. The NVA’s Soviet-style blitzkrieg consumed 1,000 tons a day in fuel for tanks and trucks, as well as munitions for tank and artillery tubes, food for troops, and medicine for the considerable casualties inflicted by a stubborn ARVN defense. American air power, with more latitude in target selection than in the past, sharply reduced the supply flow, effectively blunting the offensive.

It wasn’t. Saigon, left out of the negotiations, balked at the agreement for several reasons, especially the 100,000 NVA troops left inside South Vietnam, Hanoi’s refusal to recognize the DMZ as a political boundary (in effect, not recognizing the Republic of Vietnam’s legitimacy), and the role of the Viet Cong in the postwar political process. While the diplomatic jousting at the Paris Peace Talks continued into November, Nixon handily defeated Sen. George McGovern, the peace candidate, in the presidential election. Muddling Nixon’s political victory, however, the Democrats extended control over Congress and threatened to cut off funding for the war in January. Instead of better peace terms, Nixon ordered renewed bombing.

While Linebacker I was an interdiction campaign, Linebacker II was a coercive campaign aimed at breaking the will of North Vietnam’s leadership. The B-52, nicknamed the “Big Ugly Fellow” due to its huge size and payload capacity, epitomized the concept of shock and awe. Previously B-52s hit targets in the jungles of South Vietnam and along the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos, and, beginning in May 1969, targeted Viet Cong and NVA staging areas inside Cambodia. While some air power enthusiasts urged wider use of the eight-engine bombers, political and military considerations prompted restraint. B-52s, flying in three-plane cells, carried a massive bomb load. Earlier models were refitted for use in Southeast Asia with racks capable of carrying 105 500-pound bombs, while later models, primarily designated for nuclear missions, carried 48 bombs each. In either configuration, the B-52s obliterated targets within a quarter-mile-wide by mile-long area. With concerns about collateral damage to non-military structures and civilian casualties stoking the antiwar movement, B-52s were limited to targets on the fringes of densely populated cities. Furthermore, Strategic Air Command (SAC) leaders were wary of using B-52s over highly defended areas. In 1972 there were about 400 B-52s in the SAC inventory with the B-1 replacement in development and not anticipated for operational assignment until the end of the decade. SAC leaders coveted their B-52s for the nuclear mission under the Single Integrated Operational Plan. Nevertheless, SAC responded to the NVA Easter Offensive by increasing its Southeast Asia commitment to 210 B-52s—155 at Andersen Air Force Base in Guam and 55 at Utapao Royal Thai Air Force Base in southern Thailand. About half of these were B-52Ds modified to carry 105 500-pound bombs. SAC leaders feared losing B-52s for two other reasons: First, such a loss invited Soviet exploitation of the nation’s primary nuclear bomber. Second, the loss of B-52s to surface-to-air missiles or enemy fighters might jeopardize the case for acquiring B-1s, thus threatening the future of manned bombers and, by extension, the existence of SAC itself. While good reasons existed for unleashing the B-52s, the objective needed to be worth the risk. Ending U.S. involvement in Vietnam provided such an objective. But was SAC ready?

Target lists were generated at SAC headquarters, while mission planning at the Eighth Air Force in Guam and Utapao involved little more than specifying refueling points. Planners at SAC determined the ingress headings into the target area, the initial points for the final bomb runs, post-bomb release turns, and egress routes. This was done using plastic tape applied to acetated maps. Targeting warehouses, rail yards, petroleum storage areas, and airfields from Vinh in the southern panhandle to Hanoi and Haiphong involved what was called “extending the tape.” Since bombing undefended targets in South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia involved no significant enemy threat, planning processes became routinized. Therefore, SAC’s best planners focused on targets in the Soviet Union, Warsaw Pact countries, and China. Accordingly, planning for targets in South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fell to a non-rated (non-flying) major with limited career prospects. While competent, he was not attuned to operational and tactical combat considerations. Planning for the original three days of bombing specified for Linebacker II began on December 15. The major worked well into the night planning headings and specifying initial points, bomb release points, and post-target turns using the same criteria for hitting undefended targets outside North Vietnam. He then passed the targeting information on to his superiors for further coordination and approval. Post-target turns didn’t account for enormous radar reflections resulting from banking three B-52s, nor the fact that while banking, their electronic countermeasure pods on the bottom of fuselages would be ineffective against radar signals guiding SA-2s. Senior officers, most of them pilots or navigators, knew these basics and reviewed the plans, but signed off without raising concerns. Finally, SAC planners, who were focused on evading the more sophisticated SAMs defending the Soviet Union, had little regard for the SA-2s exported to North Vietnam. SA-2s, originally designed to shoot down high-flying U-2s and the XB-70s that were never developed, were most effective against planes flying at 30,000 to 40,000 feet, where the B-52s normally operated. SAC flew into Linebacker II with the hubris and managerial mindset that marked its early involvement in the Vietnam War and obtained similar results: lots of destruction, needless losses, and enduring controversy.

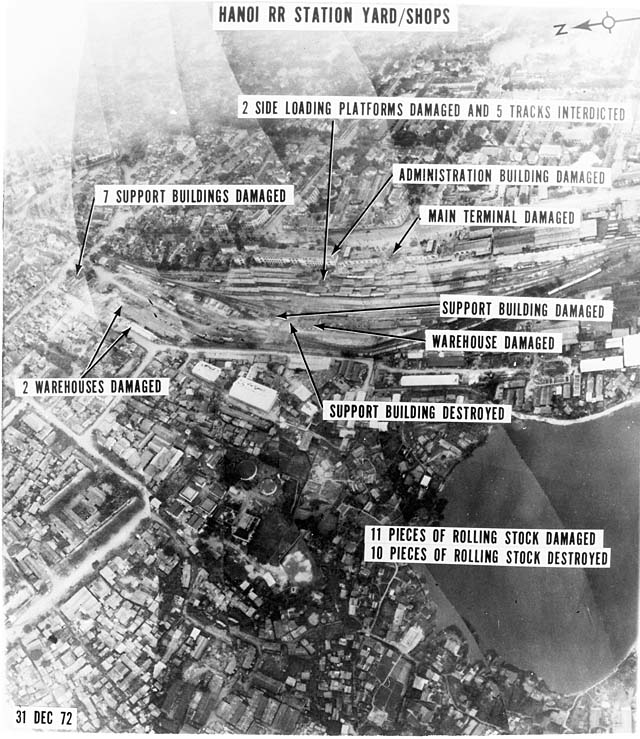

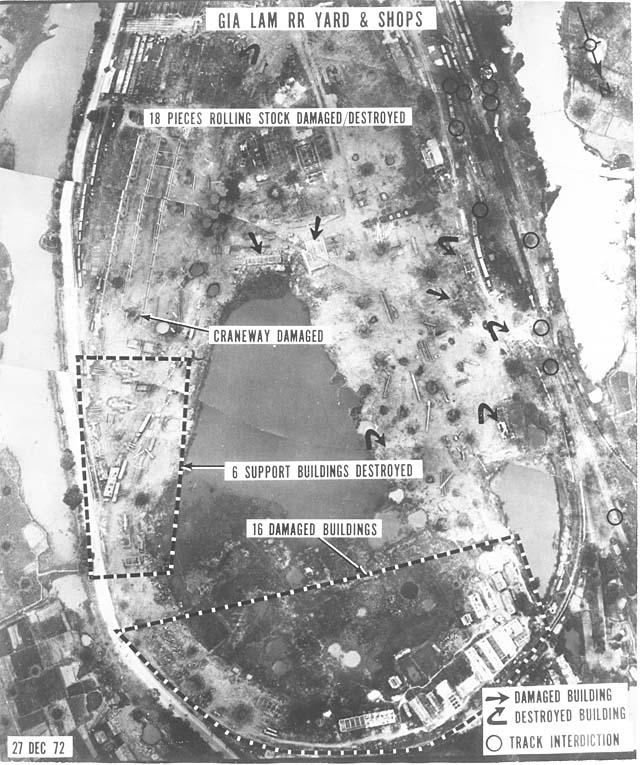

On December 14 Nixon ordered mines re-sown in Haiphong Harbor. Linebacker II kicked off on December 18 with forty-eight B-52s flying in three-ship cells designated by color—red, blue, cobalt—striking the Kinh No Storage Complex, Yen Vien Rail Yard, and three airfields near Hanoi. An SA-2 downed one B-52 over Yen Vien. At midnight thirty Guam-based B-52s pummeled targets around Hanoi. A severely damaged B-52 crash-landed in Thailand. Just before dawn a third wave struck with the loss of a third bomber. Three losses in 129 sorties made for a regrettable, but also acceptable, 2.4 percent loss rate. The second night, 93 B-52s hit the Thai Nguyen Thermal Power Plant and Yen Vien Rail Yard with no losses. On the night of December 20 three waves of bombers returned to the Yen Vien Rail Yard and Thai Nguyen Thermal Plant while also hitting storage areas around Kinh No and targets near Hanoi. This time SAMs shot down six B-52s and heavily damaged another. Six-percent loss rates, acceptable for World War II B-17 raids, were unacceptable given the relatively small number of B-52s in SAC’s inventory. Furthermore, with B-52 production having ended in 1962, there would be no replacements for lost planes. While Linebacker I had been a prototypically modern campaign involving a mix of precision-guided munitions and conventional bombing, Linebacker II was a throwback to the long bomber runs of World War II. Those first three nights bomber streams ranged up to 70 miles in length as three-plane cells flew toward their targets at approximately the same altitude, heading, and speed. Uniform post-target turn points completed the predictability and sealed the fates of six planes and thirty crewmen. The World War II mindset also led Col. James M. McCarthy, the 43rd Strategic Wing Commander at Andersen, to threaten to court-martial any pilot who jinked to avoid SAMs. This reportedly had little effect on evasive maneuvers. Nevertheless, Gen. John C. Meyer, the SAC commander-in-chief, supported McCarthy. Meyer, a fighter pilot with combat experience in both World War II and Korea, adopted the “hard ass” approach to leadership enshrined by Gen. Curtis E. LeMay during his tenure as the head of SAC from 1948-57. The problem, however, lay not with the aircrews, but with the mindset of SAC’s leaders and mission planners. Alarmed mission planners reacted to the losses by revamping strategy, modifying tactics, and changing the force packaging. The number of sorties dropped from more than one hundred to thirty-three on the fourth and fifth nights. On the fourth night, December 21, the strategy switched to hitting air defense-related targets with the loss of two bombers. Fighter-bombers suffered the losses over the next three nights. By Christmas Eve, when a 36-hour ceasefire began, SAMs had taken out eleven B-52s.

At dusk Air Force F-111 swing-wing fighter-bombers cratered runways on major airfields to prevent MiG interceptors from taking off. In fact, SAMs accounted for all B-52 losses during Linebacker II, while B-52 tail gunners bagged two MiG-21s. MiGs were used as spotters relaying the altitude and headings of incoming bomber streams to SAM operators. Meanwhile, SAC shifted mission planning to Andersen and Utapao. While SAC picked targets, Eighth Air Force planners determined ingress and egress routes, release altitudes, and turn points. The bombing on the night of December 26 got the Politburo’s attention. Instead of sending in waves of bombers throughout the night, 120 B-52s hit ten targets within two 15-minute periods. Remaining SAMs claimed two more B-52s, but the 1.66 percent loss rate was acceptable given the results. Hanoi cabled Washington asking if talks might resume on January 8, 1973. Nixon demanded that talks start on January 2 and told Hanoi the bombing would continue until they agreed. Accordingly, the following night, sixty B-52s struck airfields and warehouses around Hanoi and Vinh, along with the Lang Dang Rail Yard near the Chinese border. While SAMs claimed two more B-52s, returning crews reported that the missile firings seemed less coordinated and more sporadic. Sixty more B-52 sorties struck over the next two nights with no losses and no reported SAM firings. On December 28 Hanoi agreed to reopen negotiations on Nixon’s terms. Linebacker II ended on December 29, after eleven days of bombing the enemy’s heartland, including roads and troop concentrations in North Vietnam’s southern panhandle. Aerial attacks on NVA units inside South Vietnam intensified to encourage serious negotiations on Hanoi’s part.

Like much during the Vietnam War, Linebacker II is subject to interpretation. Many airmen claimed that a similar campaign, conducted earlier, might have concluded the war quickly and on more favorable terms. For instance, speaking to U.S. Air Force Academy cadets in 1986, when asked if the U.S. could have won the war, Gen. LeMay answered, “In any two-week period you care to mention.” Postwar analyses by Adm. U.S. Grant Sharp and former Seventh Air Force Commander Gen. William W. Momyer echoed LeMay’s opinion. But this line of reasoning doesn’t account for the fact that U.S. objectives from 1965-68 were much different than they were in 1972 when, basically, we focused on withdrawal “with honor.” Critics of the war, and of the air war in particular, lambasted what became known as the Christmas Bombing. In Europe it was unfairly and erroneously compared to the firebombing raids on Dresden and Hamburg near the end of World War II. A December 28, 1972, Washington Post editorial asked if the Christmas Bombing was not the “most senseless and savage act of war…ever visited by one sovereign people on another?” The historical ignorance displayed by that question is astounding. Former Vietnam War correspondent Gloria Emerson’s lack of objectivity—not to mention disregard for documentation—was evident in her book, Winners and Losers: Battles, Retreats, Gains, Losses, and Ruins from the Vietnam War, in which she cited an unidentified source in Hanoi to support her claim that 100,000 tons of bombs fell on “Hanoi alone” during Linebacker II. This is a physical impossibility given the number of bombers involved, their carrying capacity, distances to the target, and recycling time for the 210 B-52s available. Given that it took six months to drop 155,000 tons of bombs during Linebacker I, that should have been self-evident. During Linebacker II 739 B-52 sorties dropped 15,237 tons of bombs on North Vietnam. Air Force and Navy fighter-bombers added an additional 5,000 tons. The North Vietnamese depleted their SAM supplies to down 15 B-52s. Several B-52s crash-landed in Thailand or suffered irreparable damage. Enemy air defenses and U.S. operational losses accounted for 11 Air Force and Navy fighter-bombers and reconnaissance aircraft, along with an HH-53E Jolly Green Giant rescue helicopter. While Linebacker II severely damaged North Vietnamese military targets, the country’s cities were far from devastated. In part, that was because rail yards, petroleum storage areas, power plants, and warehouse complexes were located away from densely populated urban areas. Nor were hospitals, neighborhoods, or other non-military structures targeted, although there was some damage in Hanoi, Haiphong, and Vinh caused by stray bombs falling from severely damaged B-52s, the planes crashing after being shot down, along with SAMs and anti-aircraft shells falling back to earth. According to Hanoi’s own figures, 1,212 people perished in the capital, while 300 were killed in Haiphong. In reality, U.S. airpower could have obliterated North Vietnam far more quickly than the two-week period proposed by Gen. LeMay by bombing the dikes during the rainy season. If U.S. policymakers had been so inclined, the Air Force could have annihilated North Vietnam in one glowing and irradiated afternoon. But those options never were considered given Washington’s limited—albeit never clearly stated—strategic objectives. Linebacker II operated well within the law of proportionality prescribed by what was known as the Just War Doctrine. Although Linebacker II did not win the war—North Vietnam did that in April 1975—the bombing achieved Washington’s limited objectives by facilitating the withdrawal of U.S. forces and the return of prisoners of war. The shock-and-awe effect compelled Hanoi’s leaders to negotiate seriously and expeditiously, although they did not budge on the issues Saigon found most detestable, in that more than 100,000 NVA troops remained inside South Vietnam. Plus, while acknowledging there was a DMZ, Hanoi refused to recognize it as a legitimate national boundary, something that would have tacitly recognized the Republic of Vietnam’s legitimacy. In reality, North Vietnam’s aggression inside the South continued and then increased after the final agreements were signed on January 23, 1973. North Vietnamese forces soon moved back into Khe Sanh to establish a MiG base. New petroleum pipelines funneled fuel to NVA units in the South, while the Ho Chi Minh Trail was improved and extended. Additionally, SAM sites sprang up along the borders between western North Vietnam and occupied western South Vietnam and Laos. Those missiles were capable of covering the Trail up to seventeen or eighteen miles west.

In late February 1973 the Joint Chiefs of Staff ordered SAC to develop a massive bombing campaign targeting the Ho Chi Minh Trail with the same intensity of Linebacker II. When Operation Tennis Racket was made known to the White House, SAC was told to eliminate the strikes against SAM sites along the western borders of the two Vietnams and at the MiG bases at Khe Sanh and Vinh. Air Force leaders argued that leaving those missile sites and MiG bases intact would endanger B-52s bombing the Trail. President Nixon wouldn’t budge, though, because he already was suffering political fallout from the growing Watergate scandal. Bombing Laos was one thing—and indeed the Air Force continued to bomb Laos until mid-February—but renewed bombing of North or South Vietnam was deemed politically infeasible given the mood in Congress and among the American public. Such a campaign also might have jeopardized the release of POWs still in Hanoi’s custody. Linebacker II achieved its limited objectives of facilitating the final withdrawal of U.S. forces from South Vietnam and securing the return of American POWs. Additionally, the government of Nguyen Van Thieu remained in charge in Saigon after the final withdrawal. By early April POWs held by Hanoi were home. War being a continuation of policy with the intermingling of other means, the political outcome remains the final determinant of victory or defeat. If political objectives are not achieved, then victory cannot be claimed regardless of the effusion of blood, comparative losses, or which side prevailed in battle. In the end, the color of the flag over Ho Chi Minh City testifies most eloquently to the outcome of the Vietnam War.

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

|||||||||

Prussian military strategist Carl von Clausewitz wrote that values attached to political objectives determine the acceptable magnitude of expendable military effort, the tolerable level of sacrifices sustained, and the acceptable duration of any war. By 1972 America was war weary. Sensing this, North Vietnam forced a culmination point—at least as far as the United States was concerned—between March 31 and the end of the year. What followed did not constitute victory as the U.S. experienced it at the end of World War II, but it allowed for the withdrawal of American forces and the return of American POWs.

Prussian military strategist Carl von Clausewitz wrote that values attached to political objectives determine the acceptable magnitude of expendable military effort, the tolerable level of sacrifices sustained, and the acceptable duration of any war. By 1972 America was war weary. Sensing this, North Vietnam forced a culmination point—at least as far as the United States was concerned—between March 31 and the end of the year. What followed did not constitute victory as the U.S. experienced it at the end of World War II, but it allowed for the withdrawal of American forces and the return of American POWs. By October, with North Vietnam’s ports mined and blockaded, the vital northeast and northwest rail and road lines leading to China cut, and its divisions in the South taking a hard pounding, Hanoi seemed ready to end the war on terms acceptable to Washington. That included a ceasefire, the withdrawal of U.S. forces from South Vietnam, continued U.S. military aid to Saigon, and the return of American POWs. A Committee of National Reconciliation consisting of representatives of the Saigon government and the National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) would decide the political future of South Vietnam. During a press conference on October 26 Kissinger claimed, “Peace is at hand.”

By October, with North Vietnam’s ports mined and blockaded, the vital northeast and northwest rail and road lines leading to China cut, and its divisions in the South taking a hard pounding, Hanoi seemed ready to end the war on terms acceptable to Washington. That included a ceasefire, the withdrawal of U.S. forces from South Vietnam, continued U.S. military aid to Saigon, and the return of American POWs. A Committee of National Reconciliation consisting of representatives of the Saigon government and the National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) would decide the political future of South Vietnam. During a press conference on October 26 Kissinger claimed, “Peace is at hand.”  The original concept for Linebacker II involved three nights of bombing. Targeteers at the 544th Aerospace Reconnaissance Technical Wing, located within SAC Headquarters in the vast underground complex at Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska, compiled data on every appropriate target in North Vietnam. For seven years SAC mission planners kept track of possible SA-2 deployment sites and then carefully routed B-52s to avoid these threats. From 1965 until 1972, except for a limited number of sorties over North Vietnam’s southern panhandle, SAC avoided sending B-52s “downtown” to highly defended Hanoi and Haiphong.

The original concept for Linebacker II involved three nights of bombing. Targeteers at the 544th Aerospace Reconnaissance Technical Wing, located within SAC Headquarters in the vast underground complex at Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska, compiled data on every appropriate target in North Vietnam. For seven years SAC mission planners kept track of possible SA-2 deployment sites and then carefully routed B-52s to avoid these threats. From 1965 until 1972, except for a limited number of sorties over North Vietnam’s southern panhandle, SAC avoided sending B-52s “downtown” to highly defended Hanoi and Haiphong.  Bombing resumed at dawn the day after Christmas when “Ironhand” twin-seat F-105Fs and F-4 fighter-bombers, modified to attack SA-2 sites, pummeled North Vietnam’s air defense system. The objective had switched from persuading Hanoi to conclude the peace agreement to rendering the country defenseless and opening the possibility that continued intransigence would result in even more intensive bombing. On December 26, in one of the few daytime raids of Linebacker II, sixteen Air Force F-4 Phantoms bombed the SAM assembly area in Hanoi. The effect was that, once the remaining SAM batteries expended their missiles, there would be no replacements.

Bombing resumed at dawn the day after Christmas when “Ironhand” twin-seat F-105Fs and F-4 fighter-bombers, modified to attack SA-2 sites, pummeled North Vietnam’s air defense system. The objective had switched from persuading Hanoi to conclude the peace agreement to rendering the country defenseless and opening the possibility that continued intransigence would result in even more intensive bombing. On December 26, in one of the few daytime raids of Linebacker II, sixteen Air Force F-4 Phantoms bombed the SAM assembly area in Hanoi. The effect was that, once the remaining SAM batteries expended their missiles, there would be no replacements.