|

|||||||||||

|

March/April 2013

A Quest for Recognition: BY ARTHUR G. SHARP As U.S. Army Special Forces soldiers Capt. William Albracht and Sgt. Daniel Pierelli walked the perimeter of Firebase Kate on October 28, 1969, they realized just how precarious their situation was. Albracht and Pierelli, who were responsible for the safety of about 150 personnel on the poorly defended hill, knew they had three choices: die, be captured, or escape. They chose the last, but not until November 1, when they determined they could no longer defend the firebase. By late October about five thousand NVA troops had surrounded the firebase located in the Central Highlands of South Vietnam near the Cambodian border. Their mission was to eliminate Kate, which had been established in September 1969 to interdict NVA movements along the Ho Chi Minh Trail and restrict the enemy’s ability to attack Special Forces camps in the area. After accomplishing that, the NVA’s plan was to capture the city of Ban Me Thuot, effectively cutting South Vietnam in half. This was a momentous period in Albracht’s life: The 21-year-old was the youngest captain in Special Forces, and this was his first time in combat. Kate was his first command. It would be a memorable one. Kate’s location was problem No.1 for Albracht. It was set on a hilltop, but the NVA had control of the nearby road and could fire with impunity from the nearby “neutral” country of Cambodia. The only way to move supplies and personnel on and off the base was by helicopter. A variety of aircraft such as fighter-bombers, observation planes, and heavily armed Spooky gunships and Shadows complemented the choppers and protected the troops on Kate. Despite all that support, Albracht knew it was not enough. Pierelli, a weapons specialist and Special Forces advisor to the Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) Company at Trang Phuoc-Ban Don, arrived on Kate first, on October 27. What he saw caught him by surprise. The NVA had not yet attacked Kate, so the troops were more interested in playing volleyball and relaxing than in setting up defensive positions. That was the first thing he and Albracht addressed the next day when the captain arrived. Albracht and Pierelli immediately developed a plan to increase patrols around Kate, allowing them to gain badly needed intelligence on the NVA in the area. This would also allow them to strengthen their defenses. They were just in time. The NVA began its siege of Kate in earnest on the night of October 28 when a CIDG patrol ran into the forward elements of an NVA regiment. NVA troops, who outnumbered Kate’s defenders by about forty to one, launched their first assault at about 11:30 the next morning. The number of assaults increased as the days went by. NVA troops attacked with small arms fire, mortars, artillery, and B-40 rockets. Chaos reigned as mortar rounds, rocket, and artillery shells rained down on the base day and night. They attacked with small-arms fire from all directions, but Kate’s defenders drove them off. Albracht and Pierelli assessed their situation quickly. They had at their disposal two Vietnamese Special Forces members, one Camp Strike Force company of about one hundred men, sixteen members from a relieved company who had stayed behind, a forty-man Camp Strike Force platoon from Detachment A-236 at Bu Prang, and the twenty-seven or so artillerymen from 1/92nd and 5/27th Artillery under operational control of 5/22nd Artillery. The artillerymen had only one 105mm and two 155mm howitzers in their arsenal. Most of the troops were Montagnards from Camps A-233 and A-236 who provided security for the artillerymen. The attacks were not as bad at night, as American Spooky gunships forced NVA troops to keep their heads down. But the enemy was wearing down Kate’s defenders with its ferocious attacks at dawn and dusk when the gunships arrived and departed.

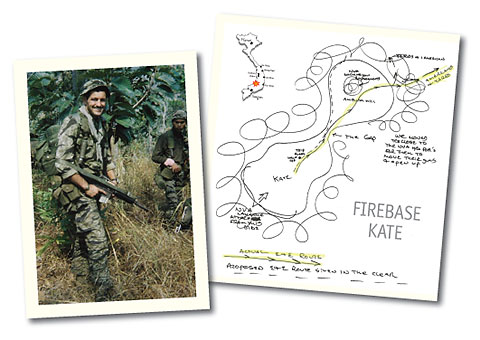

As the situation on the ground became more desperate, Air Force Capt. Al Dykes, the navigator on a Spooky gunship, call sign Spooky 41, told Albracht that Kate was receiving more enemy fire than any other American outpost in South Vietnam. That was not exactly what Albracht wanted to hear. He realized that Kate no longer could defend itself. To make matters worse, the ARVN commander refused Albracht’s request for aid. So Albracht radioed Special Forces Operations and requested permission to escape. Albracht was told by Special Forces commanders to get his men out of Kate any way he could. Daring helicopter pilots delivered supplies and evacuated wounded troops. But as the NVA’s relentless attacks continued, it became more dangerous for them to fly near the base. By November 1 the NVA artillery had the base zeroed in and began pounding it with an ever-increasing number of rounds, turning Kate into what Albracht described as “an impact area, and no longer a functioning firebase.” As a result, helicopter support ended. That made the troops even more aware of their vulnerability and their mortality. On the morning of November 1 Albracht decided it was time to evacuate. He and Pierelli drew up an escape-and-evasion plan, arranged for gunships to protect them as they left Kate, and explained carefully to the troops how they would link up with a Special Forces Mike Force detachment waiting for them in a concealed position about three miles away. Then they spiked their gun tubes and destroyed the artillery ammunition, records, code books, and anything else the NVA might find useful. No American soldiers were left at Kate. Albracht left the fate of the Montagnard dead to the tribal elders, who, realizing how dangerous the situation was, decided to leave them at Kate. Albracht was extremely apprehensive about the escape. He and Pierelli would be leading about 150 men who had little or no infantry training into pitch-black jungle at night. In his mind they were dead men walking. He knew that the NVA would be looking for them and would not be taking any prisoners. Although suffering from sleep deprivation from the five-day siege and also suffering from his wound, at about 10:00 p.m. Albracht commanded the troops to move out. Immediately, the NVA lit the area with illumination flares as the men fled down the North Slope, through a small gap in the wood line, and up the side of Ambush Hill. The NVA apparently knew which way Albracht’s troops were going and set up an ambush to intercept them. But luck was with them. CIDG forces knew about the ambush, so they deviated from the escape route, which saved many lives. About half of the Montagnards and one artilleryman went in the other direction and made their way safely to the Special Forces camp at Bu Prang. Only one soldier, West Virginian Michael Norton, was lost in the dense jungle and killed by the NVA. His body was never recovered.

Miraculously, Albracht wound up crossing the open field three times, on each occasion exposing himself to the enemy, to make sure his men were safe. It was 3:00 a.m. on November 2—five hours after the withdrawal had begun—when the men of Kate linked up with the Special Forces Mike Force. In what seemed like an eternity, Albracht and his troops had traveled only two-and-a-half miles. It took them eight more hours to reach safety at the Special Forces camp at Bu Prang. Many of the men would later say that they owed their lives to Capt. William Albracht and Sgt. Daniel Pierelli. They were no longer dead men walking.

After Albracht returned to the United States, he completed a quarter-century career with the U.S. Secret Service. During that time he guarded five American presidents and many other high-ranking officials. He has been an active life member of VVA since the mid-1990s. After returning to his hometown of Rock Island, Illinois, in 2005, he served on the board of directors of Quad Cities Chapter 299 for five years and was its president for two terms. In addition, he was the chapter’s secretary for two years and acted as chair, co-chair, and member of many committees. Bill Albracht moved back to Washington, D.C., but he retained his membership in Chapter 299. Being involved with VVA activities made it impossible for him to forget Firebase Kate entirely. That was also true for many of the men who had served with him there. Many chafed that Albracht had never received any special recognition for his role in leading the escape that saved their lives. Ironically, he had received a Silver Star, but for actions during an NVA assault on the camp at Bu Prang on November 2, the same day that he and his men from Kate arrived there. Joe Murphy, a Vietnam veteran and a friend of Bill Albracht, told the story of Firebase Kate to Ken Moffett, a Vietnam veteran and Chapter 299 member who was working on veterans’ issues for U.S. Rep. Bobby Schilling of Illinois. After consulting with several other congressional offices and conducting a thorough investigation of what happened at Kate, Shilling’s office submitted a recommendation to the U.S. Army Human Resources Command at Fort Knox on July 20, 2011, that Albracht be awarded the Medal of Honor. The 165 pages of documents that Moffett put together contained eyewitness statements from the men who survived the siege at Kate, after-action reports, maps, photos of Kate before and after the siege, and tapes of the radio traffic between Albracht and Al Dykes (the Spooky gunship navigator) recorded during the siege and evacuation of Kate. “What Albracht did at Kate is the kind of stuff guys get recommended for the Medal of Honor,” a congressional aide who had worked on other MOH recommendations told Moffett. Three paragraphs in the document are particularly telling: “Every U.S. soldier who survived the siege of Kate received an award for valor except Captain Albracht. The commanding general of the II Corps Tactical Zone in Ban Me Thuot had arranged a ceremony to present an Impact Award to Captain Albracht, and had dispatched a helicopter to the Special Forces camp at Bu Prang to transport him to the ceremony despite the high winds that had grounded all other helicopters. “As this helicopter landed at Bu Prang and the captain was preparing to board it, he learned that four U.S. soldiers of a Mobile Strike Force had been gravely wounded in recent firefights around Bu Prang but could not be airlifted by medevacs because of the high winds. “Without hesitation, Captain Albracht asked his pilots to take the wounded with him and transport them before taking him to Ban Me Thuot. By the time the helicopter had delivered the wounded to a distant field hospital and brought the captain to Ban Me Thuot for the ceremony, the commanding general had already departed. The captain missed the award ceremony, which was never rescheduled.”

Forty-three years later Albracht received long-awaited recognition for his valor and leadership at Kate. But it was not the Medal of Honor his troops had sought. The requested award was downgraded to a Silver Star. William Albracht accepted the Silver Star—his third—at a ceremony at the Rock Island Arsenal, Ill., on December 15, 2012 (see photo above). His supporters, however, are not satisfied. They have vowed to ask for a review of the request for the Medal of Honor. If they demonstrate the same tenacity Bill Albracht displayed at Firebase Kate, they may get their wish. Albracht may yet add the Medal of Honor to his collection of awards that also includes three Silver Stars, three Purple Hearts, five Bronze Stars (three for valor), two Air Medals (one for valor), and an Army Commendation Medal (for valor). Editor’s Note: Reginald Brockwell, an artillery officer in Vietnam who was in charge of setting up firebases, including Kate, and Ken Moffett contributed to this article.

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

|||||||||||

Albracht’s troops suffered a growing number of deaths and injuries. Morale plummeted as food, water, ammo, and medical supplies dwindled drastically. Albracht had taken shrapnel in his arm on October 29 as he directed a medevac helicopter attempting to land at the firebase. He was given the opportunity to leave with the other wounded, but refused—choosing to stay at Kate to lead the remaining besieged troops.

Albracht’s troops suffered a growing number of deaths and injuries. Morale plummeted as food, water, ammo, and medical supplies dwindled drastically. Albracht had taken shrapnel in his arm on October 29 as he directed a medevac helicopter attempting to land at the firebase. He was given the opportunity to leave with the other wounded, but refused—choosing to stay at Kate to lead the remaining besieged troops. NVA troops were everywhere. For all Albracht knew, he was walking into one of their encampments. He repeated his question several times as he approached the wood line nearly a hundred yards from where the men of Kate lay hidden in the jungle. Finally, SFC Lowell Stevens, the Mike Force ground commander, grabbed Albracht’s arm and told him to get the rest of his troops, as they had to evacuate immediately.

NVA troops were everywhere. For all Albracht knew, he was walking into one of their encampments. He repeated his question several times as he approached the wood line nearly a hundred yards from where the men of Kate lay hidden in the jungle. Finally, SFC Lowell Stevens, the Mike Force ground commander, grabbed Albracht’s arm and told him to get the rest of his troops, as they had to evacuate immediately.