|

|||||||||

|

January/February 2012

Collateral Damage: BY GERSHOM GORENBERG “You will certainly note,” Hal Saunders said, “that we had another problem on the other side of the world.” Saunders spoke in the quiet voice of a lifetime diplomat. He was explaining why the Johnson administration let the Arab-Israeli conflict fester after the Six-Day War of 1967. Back then, he said, the “top levels of the U.S. government” were distracted and exhausted by that other “problem”—Saunder’s immensely understated term for the Vietnam War. During that critical period of history, Saunders served as the National Security Council’s staffer responsible for the Middle East. His description of a hamstrung superpower points to a kind of rarely noticed collateral damage from the Vietnam War: When the United States was tied down militarily in Southeast Asia, when war there dominated America’s diplomatic agenda abroad and its political debate at home, it was less able to cope with challenges elsewhere on the globe. The after-effects are still being felt. The Middle East provides the prime example. Vietnam hobbled President Lyndon Johnson’s efforts to keep war from breaking out between Israel and its Arab neighbors in the spring of 1967. What’s more, the war also sapped the administration’s determination to reach a full peace afterward. The neglect continued under Richard Nixon. Only after the Paris Agreement of 1973—and after another disastrous Middle East war led to a face-off with the Soviet Union—did the United States make a serious push for Arab-Israeli agreements. On May 15, 1967, at their morning meeting, National Security Adviser Walt Rostow and his staff discussed a disturbing report from Cairo: The day before, thousands of Egyptian troops had marched through the city, passing the U.S. Embassy. Whether or not the NSC realized it, the report was like a dark puff of smoke rising from a volcano—a sign that the Middle East was about to erupt. For months beforehand, Israeli and Syrian forces had sporadically clashed on their shared border, and Palestinian guerrilla groups had launched raids into Israel from both Syria and Jordan. Now, based on a false warning from the Soviet Union that Israel was preparing to retaliate by invading Syria, Egyptian President Gamel Abdel Nasser decided to mobilize his army. From Cairo, he sent it across the Suez Canal into the Sinai Peninsula. Nasser, it seems, aimed at facing Israel down and renewing his shopworn credentials as the defender of the Arabs. On May 16 he demanded that U.N. Secretary General U Thant remove peacekeeping forces that the United Nations had deployed in the Sinai for a decade. Their job was to prevent war between Egypt and Israel and to ensure that the Straits of Tiran, the gateway to Israel’s southern port of Eilat, stayed open. The tankers that brought Israel’s oil from Iran came through the straits. To the world’s surprise, and probably to Nasser’s, the U.N. leader acceded and pulled out the peacekeepers. Nasser, trapped by his own bravado, ordered the straits closed. In Israel, meanwhile, the streets were emptying of men as the military reserves—the bulk of the Israeli army—were called up. The crisis put Lyndon Johnson’s administration in an impossible bind. U.S. public opinion favored Israel, and Johnson himself was a strong supporter of the Jewish state. In Cold War calculus, Israel was aligned with America; Egypt and Syria were Soviet clients. On the other hand, as Saunders and Rostow had stressed in policy memos just a few weeks before, America had huge investments in Arab oil states. It needed to bolster “Arab moderates,” pro-Western countries such as Jordan and Saudi Arabia, and keep Soviet influence from spreading. America couldn’t afford to be seen as simply pro-Israel and anti-Arab. Making the dilemma sharper, the United States had an explicit commitment to protect “the right of free and innocent passage” of shipping through the Straits of Tiran. The Eisenhower administration had made that promise ten years earlier when Israel withdrew from the Sinai after an earlier war with Egypt. America also had affirmed that if Israeli ships were prevented from using the straits, Israel was entitled to “exercise its inherent right of self-defense.”

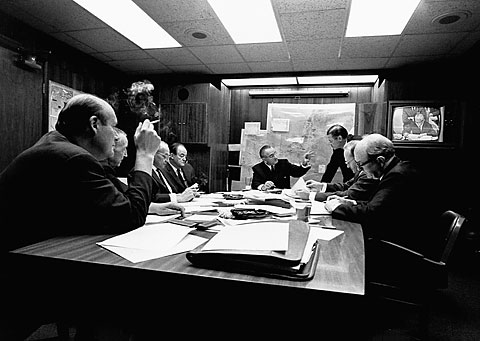

In Washington, it seemed entirely possible that if a small ally went to war against large, Soviet-backed adversaries, it might need American military help to survive. Yet as Secretary of State Dean Rusk noted when he met with the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on May 23, 1967, the United States already had 450,000 troops in Vietnam. Sen. Albert Gore (D-Tenn.), the father of the future vice president, told Rusk that “because of the domestic political pressures the chances are overwhelming that this country would not [be willing to] see Israel destroyed.” Yet other senators warned Rusk that “we have enough troubles in Vietnam,” that America was “overextended,” that more than ten thousand Americans had already died in Southeast Asia. In fact, as Sen. J. William Fulbright (D-Ark.) suggested, this was the reason for the new crisis. “Do you really think Nasser would have acted as he has if we were not preoccupied with Vietnam?” he challenged Rusk. So asking Congress to permit using troops looked like a poor idea. When Israeli Foreign Minister Abba Eban met with Johnson on May 26, the President warned him: “Israel will not be alone unless it decides to go alone.” In other words: Don’t attack; we can’t back you up. To defuse the crisis, the administration tried to organize an international convoy to sail through the Straits of Tiran and call Nasser’s bluff. But other countries had cold feet. And meeting again with the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Rusk heard concerns that the convoy plan risked mission creep: The United States would be alone and might have to use military force against Egypt. Afterward, Rusk described the committee as suffering from “Tonkin Gulfitis”—a reference to the 1964 congressional resolution authorizing military action in Vietnam. Indirectly, he was admitting that the senators didn’t want to give Johnson another blank check for war. In short, the Vietnam experience tied Johnson’s hands in dealing with the Middle East. In Israel, patience ran out. Jordan and Iraq had joined the Egyptian-Syrian coalition. The Israeli cabinet decided it couldn’t risk waiting for the Arab armies to invade. H-hour was 7:10 a.m. on June 5, 1967, when waves of Israeli warplanes took off, swept beneath enemy radar, and struck Egypt’s air bases, destroying its planes on the ground. Less than an hour later, Israeli tanks rolled into Sinai. Over the next six days, Israel experienced its own high-speed mission creep. As Jordan and Syria joined the war, Israel went on the offensive on two more fronts. By the time a U.N. ceasefire went into effect, Israel had conquered the Sinai Peninsula, the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, and the Golan Heights. In Washington, the shock waves had several effects. One was bureaucratic. Rostow was too busy with Vietnam to cope with another war. Johnson asked Rostow’s predecessor, McGeorge Bundy, to come back to the White House temporarily to lead an executive committee to handle the Middle East. Johnson, in effect, needed a second national security adviser. The move demonstrated a principle that the former head of strategic planning in the Israeli general staff, Brig. Gen. Shlomo Brom, stated in an interview many years later: “Attention is also a limited resource”—even for a superpower. When Bundy returned to his job at the Ford Foundation that summer, the attention deficit in the White House would be even greater. A second effect, as Saunders said later, was a large sigh of relief about getting “through this [war] without any further call on U.S. support.” The fears that the United States would have to put boots on the ground in the Mideast had proved unfounded. Bundy alluded to this in his July 1967 memo to Johnson that outlined his ideas for Middle East policy. “The U.S. had a great interest in the ability of Israel to defend herself against her neighbors,” he wrote. That is, it was easier for America to keep Israel well supplied with arms than to risk having to provide American troops.

Israel and America still had conflicting policy interests, Bundy noted. America needed to maintain warm relations with moderate Arab countries. “We can and do support [Israeli] withdrawal” from territory conquered in the war, he wrote. But Washington had to be careful about using arms supplies as a means of pressure because it wanted Israel to be able to defend itself. Logical as this conclusion was, the emotional force behind it came from the administration’s Vietnam-induced weakness. Though Israeli and Arab positions were far apart, openings existed for diplomacy. Jordan’s King Hussein was particularly eager to negotiate with Israel. But as Saunders said when I interviewed him in 2004, “We weren’t up to taking on the kind of diplomatic initiative [shown] in the Kissinger shuttles after the ’73 war”—meaning nearly full-time involvement of the Secretary of State, with the President stepping in when needed. In 1967, Vietnam was consuming the President and Secretary’s time. So the administration’s key effort on the Middle East was devoted to passing U.N. Security Council Resolution 242 in November 1967. The resolution called for Israeli withdrawal from “territories occupied in the recent conflict” and an end to “states of belligerency.” It also turned the job of negotiating peace to a U.N. emissary. That freed the U.S. of the burden, but produced no progress toward peace. Meanwhile, during the first months after the war, the administration under-reacted to a critical development: Israel began building settlements in the occupied territories. On September 25, 1967, the U.S. embassy in Tel Aviv reported that the Israeli cabinet had given its first approval for a settlement in the West Bank. The cable cited a top Israeli journalist who explained that the government’s policy was to “establish facts quietly rather than making noisy statements.” Each settlement marked a spot from which Israel did not intend to withdraw. At his noon briefing the next day, the State Department spokesman issued a mild rebuke. By the next February, Israeli Prime Minister Levy Eshkol reported that ten settlements had been set up and an additional seven approved. Several weeks later, the State Department ordered the Tel Aviv embassy to remind the Israeli government of America’s position that building settlements in occupied territories violated international law. That protest, however, was not public. In the years that followed, junior diplomats at the embassy and the U.S. consulate in Jerusalem tracked settlement activity, but found that their reports generated little interest in Washington. The dots on the map marking new settlements spread in the Golan Heights and West Bank, in Sinai and the Gaza Strip. “I can tell you—I have always in the back of my mind kicked myself for not having said [to Israel] that we just can’t allow this,” Saunders said years later. “I don’t think we raised the kind of alarm bells that I wish we had.” The explanation for not paying enough attention to settlements, he said, was that “problem on the other side of the world.”

When Richard Nixon became president in 1969, the Middle East stayed on the back burner. “The Vietnam War was his overriding initial priority,” William Bundy (brother of McGeorge) wrote in A Tangled Web: The Making of Foreign Policy in the Nixon Presidency. Relations with the Soviet Union were conditioned on whether Moscow would lean on Hanoi to make peace. The opening to Communist China was a way of pressuring Moscow. Nixon’s belief that the Arab-Israeli conflict could be put off till later was demonstrated in how he split up foreign policy responsibilities between his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, and Secretary of State William Rogers. Kissinger got the important jobs, such as Vietnam and Soviet-U.S. relations. Rogers was assigned areas where progress was unlikely—which included Middle East peace. The division of labor suited Kissinger, who preferred to leave any Israeli-Arab peace bid until “those who would benefit from it would be America’s friends, not Soviet clients,” as he wrote in his memoirs. The stalemate in the Middle East could continue until Egypt and Syria realized that they were better off switching sides in the Cold War. Before Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir visited Washington in the autumn of 1969, Kissinger advised Nixon that “a continuing deadlock” between Israel and the Arabs was in America’s interest. “It would demonstrate Soviet impotence” and either force Egypt to break with Moscow or push the Soviets to pay for American help to prevent another Mideast war. In Kissinger’s portrayal, the Arab-Israeli conflict was a small corner of the Cold War chessboard; Vietnam was the center of the game. Focused on Southeast Asia, Kissinger and Nixon ignored signals from the Middle East. In September 1970, Nasser died. Anwar Sadat succeeded him as president of Egypt. Interviewed that December in The New York Times, Sadat defined his “first priority” as ending Israel’s occupation of the Sinai Peninsula—and said he was willing to make peace with Israel to reach that goal. Afterward, though, Sadat repeatedly threatened to go to war if that was the only way to regain Egyptian land. When Nixon visited Moscow in May 1972 for a summit with Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev, the Middle East barely figured in the talks. The agreed communiqué at the summit’s end did not explicitly mention an Israeli withdrawal. Sadat felt sold out by Moscow. In July he evicted the Soviet Union’s 15,000 military advisers from Egypt. On one hand, the move freed Sadat from Soviet military and diplomatic reins. On the other, it created exactly the opening to America that Kissinger claimed to have sought. Sadat’s intelligence chief sent a secret message to Kissinger proposing a high-level U.S.-Egyptian meeting. Eventually, “Kissinger begged off because of his total involvement in Vietnam negotiations,” William Bundy recounts. As Kissinger wrote in his memoirs: “The seminal opportunity to bring about a reversal of alliances in the Arab world would have to wait until we had put the war in Vietnam behind us.” At last, in January 1973 the Paris Agreement was signed—not bringing peace to Vietnam, but allowing America to withdraw its troops. Even afterward, it took Kissinger and Nixon time to turn away from Southeast Asia and devote attention to the Middle East. Nixon, it seems, was already distracted by Watergate. Kissinger thought negotiations would be impossible before Israeli elections scheduled for that October, and shared the confidence of Israeli intelligence that Egypt was unready for war. That confidence proved disastrous. On October 6, 1973, Egypt and Syria launched a massive surprise attack on Israel. Sadat did not plan or expect to retake the entire Sinai. He did plan to seize a narrow strip of land and force the United States to engage diplomatically. To prevent an Israeli defeat, the U.S. began a massive arms airlift. By the war’s end two and a half weeks later, Israel had counterattacked and surrounded the Egyptian Third Army. To complete the encirclement, it ignored a U.N.-imposed ceasefire—at Kissinger’s urging. When the Soviet Union threatened to intervene, the United States repositioned B-52s that could carry nuclear weapons. A hint at why Kissinger—now secretary of state—took the dangerous gamble on the final Israeli push comes from minutes of a meeting with his staff the day it happened. The United States, he said, “could not tolerate” the defeat of “another American-armed country… by a Soviet-armed country.” After Vietnam, that is, America needed a clear Israeli victory. Nonetheless, the 1973 war had the effect that Sadat sought: America finally launched an intensive diplomatic effort. Kissinger shuttled between Middle Eastern capitals, leading to Israeli-Egyptian and Israeli-Syrian interim agreements. In 1977-79 President Jimmy Carter brokered the Israeli-Egyptian peace accord, under which Israel withdrew completely from the Sinai. But the delay in diplomacy caused by the Vietnam War exacted a price. Israel was already entrenched in the West Bank, and Kissinger failed to cut a first-stage deal between Jordan and Israel involving a partial withdrawal. In October 1974 the Arab League gave the Palestine Liberation Organization, rather than Jordan, the mandate to negotiate the future of the West Bank and Gaza. But before the PLO and Israel were ready to make the interim agreement known as the Oslo Accords, nearly two decades had passed. A final peace agreement has still eluded the sides. No one can know for sure if peace efforts would have been more successful in the summer of 1967. What’s certain is that America wasn’t available to try. Even the world’s most powerful country, it turns out, has limited resources—in military, political, and economic terms, and even in the amount of time and energy its leaders have available. By deciding to commit itself to a major military effort, it is also deciding that it will have less ability to respond to challenges elsewhere. That’s one more of the many lessons of Vietnam.

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

Vietnam Veterans Memorial |

|||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

|||||||||