|

|||||||||

|

January/February 2012 The Defenders of Dak To

BY MARC LEEPSON

That long, tense, and bloody engagement is not well known, but has a special place in the annals of the war in Vietnam. How special? It likely was the most sustained combat in the Vietnam War that did not involve any large American infantry units. The fighting at Dak To, instead, was fought mainly by support troops: three companies of the 299th Combat Engineer Battalion and the 15th Light Equipment Company. Those men defended the big American base and air strip at Dak To against the North Vietnamese Army’s 66th Infantry Regiment and 40th Artillery Regiment from January through July of 1969. How did some six hundred bulldozer drivers, crane and front-end loader operators, mechanics, medics, cooks, clerks, truck drivers, and other non-infantrymen wind up defending the mountain against thousands of NVA troops? The answer has to do with the start of Vietnamization, the American high command’s strategy of turning the war over to the South Vietnamese military. One of the first moves in the Vietnamization process was the withdrawal of U.S. 4th Infantry Division troops from Dak To late in 1968. The 42nd Regiment of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam were to take the Ivy Division troops’ place at Dak To. Or at least that was the plan, but the ARVN regiment never showed up. “It was probably the most unique situation of the Vietnam War,” former 299th medic Mike Zimmer said. “Dak To was the first place for Vietnamization, and the 4th Infantry Division pulled out. But the 42nd ARVN refused to replace them like they were ordered to. And we couldn’t leave. And there we were, surrounded by thousands of NVA.”

It rained a lot. And there were serious re-supply problems. “When we got ready to leave, every piece of equipment ran,” Johnnie Sanders, a Warrant Officer who served as the 299th Battalion maintenance officer, said. “They didn’t look good, but they ran. The men didn’t look good, either. They wore flak jackets without shirts. They put duct tape on their boots.” The combat engineers’ mission at Dak To also included mounting minesweeping patrols to try to keep the roads open from Dak To to the nearby American outposts at Ben Het and Tan Canh. Nearly every day while they were under siege by the NVA, seven-man minesweeping patrols moved out onto the roads to Ben Het and to Tan Canh. Those were tense, dangerous missions. Additionally, these minesweeping patrols frequently came under fire. As did the men of the 299th who were sent out to work on paving the road between Dak To and Ben Het. The only help from American combat arms units that the engineers received at Dak To came from elements of two Firing Batteries and the Headquarters and Service Batteries of the 1/92nd Artillery, along with several Americal Division dusters, the ubiquitous tank-like vehicles armed with 40mm guns. There also was a tiny Air Force detachment at Dak To that took care of runway operations at the air strip. “The American infantry was gone,” said Jay Gearhart, who was a 20-year-old bulldozer operator with the 299th’s 15th Light Equipment Company at Dak To in 1969. “We were the infantry.” Because the men of the 299th were not infantrymen, they had not been issued the standard Vietnam War infantryman’s weapon, the M-16. The engineers wound up doing their defending with M-14s. “They told us, ‘You’re not infantry, you don’t need M-16s,’ ” Zimmer said. “As it turned out, we ran out of ammunition and had to take belts from the M-60s [machine guns] and use them” in the M-14 magazines.

To this day the men of the 299th Engineers refer to themselves as the Brotherhood of Dak To Defenders. The nickname reflects the camaraderie that they still feel, a camaraderie that developed while defending the mountain during the long, tense NVA onslaught. We caught up with many of the men of the 299th in July during their ninth annual reunion, where we spoke to Gearhart, Zimmer (the current president of the group), Sanders, and many others about the singular events that played out at Dak To during those six long months in 1969. The Dak To veterans said that the first four months, from late January to early May, were relatively calm. During that time the NVA delivered light pressure—the occasional ambush, a mortar attack here and there, a couple of sapper missions.

There were many direct hits; there were many more hours of nervous anticipation, with the men on constant alert. A total of nineteen engineers lost their lives; scores were wounded. Six artillerymen were killed in action, and twenty-five were wounded. Overall, the casualty rate was an astounding 45 percent. At around 12:30 in the afternoon of May 9, the NVA launched a massive rocket, artillery, and mortar attack. Two days later, as night was falling, the NVA rained down dozens of B-40 rockets and mortar rounds on the engineers on the mountain, followed by small arms fire from two directions. Then six NVA sappers made it through the perimeter and started throwing hand grenades and satchel charges. The sappers wound up in the 15th Engineer Company’s mess tent. They did not survive the blasts from the grenades that engineers threw in after them. For most of the next two months, the Defenders of Dak To endured almost non-stop artillery barrages. “The worst of it was all the incoming,” Gearhart said. “It was constant every single day. Tents were torn up. You slept on the ground.”

Late in the afternoon of May 23, nineteen 122mm rockets flew into the 299th’s compound. “The 122s were big enough you could see them flying through the air,” Zimmer said. “They looked like flying telephone poles.” Four artillerymen perished in that attack and eleven were wounded. The deadliest single incident took place on May 28, 1969, a date seared into the memories of every Dak To Defender. That evening a 122mm NVA rocket came screaming directly into the 15th Light Equipment’s headquarters bunker. The heavily sandbagged bunker, sunk some twenty feet in the ground, was crowded with engineers, including a thirty-man reaction force. Nine men, including Company Commander Franklin L. Koch and 1st Sgt. Dudley J. Benefiel, Jr., were killed, and nineteen were wounded. Dan Heidrich, a cook from Linton, North Dakota, was manning a mortar tube on the perimeter when the first rockets hit. “We were always watching for rockets,” he said. “We saw one take off through our surveyor’s instrument. I could almost touch it as it sailed right over my head. It hit right in the doorway of the bunker. I was one of the guys who helped remove bodies from the bunker.”

Jay Gearhart and Earl “Bud” Baker, a crane operator from Folsom, California, were among those inside the bunker when the rocket hit. “We got blown away,” Gearhart said. “The next thing I know, I’m in a heap with a bunch of other guys. We couldn’t see. We couldn’t breathe. Couldn’t hear. Guys were scrambling to the light to get out of there. The entrance was gone and we had to claw our way out of there. There were bodies laying everywhere. Thank God for our medics, Ron Culpepper and Mike Zimmer. They did triage and tried to treat the more seriously wounded.” “The place went dark,” Baker added. “The roof was gone. The First Sergeant was really bad off. My face was burned, but I thought I was okay until I passed out. I woke up in the hospital with shrapnel in my face.” Two days later, on May 30, a helicopter carrying Battalion Commander Newman Howard landed in the compound. More than a few 299th men were shocked also to see Gen. Creighton Abrams, who succeeded Gen. William Westmoreland as MACV Commander in 1968, step out of the helicopter, along with his entourage. They were even more surprised when Gen. Abrams said that he had been told there were ARVN troops at Dak To.

“Today was far from a regular day,” Hickey wrote. At around 1:00 a.m. the NVA began a barrage of small arms fire, along with the first of fifty-nine mortar rounds and fifteen B-40 rockets that hit Dak To that day. Five men were wounded. One enemy soldier was killed. Later that morning, the daily minesweeping operation was ambushed on the road to Ben Het with rockets, small arms, and machine-gun fire. It didn’t help morale that the ARVN troops responsible for the patrol’s security fled as soon as the firing began. The South Vietnamese troops “started running back down into the ditches,” Hickey wrote, “leaving the seven-man minesweep team.” Soon after that, rockets killed two 299th men: Hickey’s former squad leader, Sgt. Philip Burfoot, who took a direct hit, and 21-year-old PFC Joseph Mott of Buffalo, New York. Two wounded engineers barely escaped with their lives. “The NVA came charging over the bank, so [the wounded men] played dead,” Hickey said. “The NVA took their weapons and gear right off of them. I’m not sure why they didn’t [kill them].” The minesweeping team’s truck driver radioed back to the compound for help. About twenty minutes later the two dusters, two five-ton truckloads of men, and a truck with four 50-caliber machine guns arrived on the scene. Hickey was with the group, driving the CO. Life photojournalist Larry Burrows hitched a ride with them. “There must have really been a lot of NVA dug in there,” Hickey wrote to his wife. “You could hear AK47s cracking overhead. It was really scary. A chopper tried to land to pick up the wounded, but it got shot up and just barely made it the two miles back to the compound.”

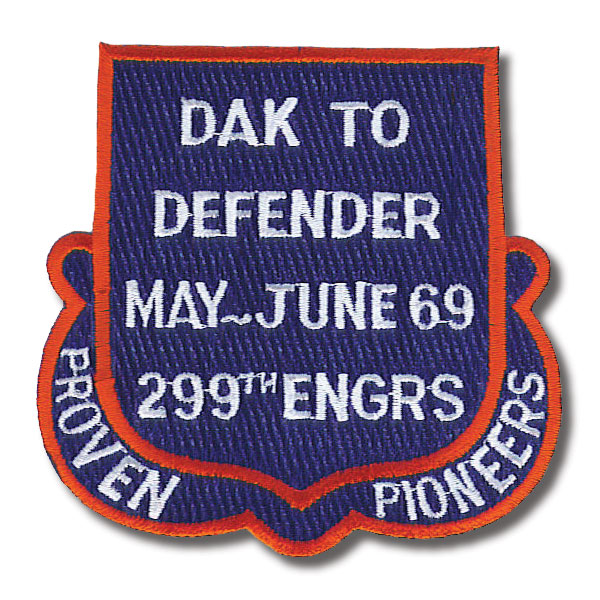

“They took a lot of ARVN and two dusters this time,” Hickey said. “When they got back to the ambush site, they got small arms fire again and the ARVNs” left the scene again. “Back to the rear they went. This time the minesweep came back in.” Larry Burrows’s photos of the ARVN troops in the ditch were prominently displayed in the September 19, 1969, issue of Life under the headline, “A Case of Cowardice Under Fire.” The Army brass were not happy with that, but the men of the 299th felt the article and photos perfectly summed up their situation. A few weeks later the 299th Combat Engineers began sporting a new homemade unit patch. Above the battalion motto of “Proven Pioneers” were the words, “Dak To Defender.” That patch has been modified today to read: “Dak To Defender, May-June 69. 299th Engrs.” The enemy shelling and probing continued until July 6. “Then, all of a sudden, on July 7 it ended,” Hickey said. A little recon confirmed that the NVA had gone. On July 19 the last of the Dak To Defenders left. The survivors felt relief, pride, and not a small amount of bitterness. “A lot of us believe that we were left as bait to draw the NVA out of the mountain,” Mike Zimmer said. “But the worm didn’t get bit. The North Vietnamese realized the government was setting a trap.” Meanwhile, “we took 45 percent casualties, every other man was hit. Every day there was incoming, incoming, incoming.” “As everything seemed to be falling apart around us, we hung tough,” Gearhart said. “We would not let the NVA overrun us, no matter what. If it weren’t for the 1st of the 92nd Artillery’s counter battery fire and the dusters, none of us would be here.” In 1970 the 299th and the 1/92 received the Valorous Unit Award, the equivalent of a Silver Star, for their actions at Dak To. The 299th also received the Republic of Vietnam’s Cross of Gallantry unit citation.

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

Vietnam Veterans Memorial |

|||||||||

8719 Colesville Road, Suite 100, Silver Spring. MD 20910 | www.vva.org | contact us |

|||||||||

When they realized they were on their own, the men of the 299th used their engineering skills to try to protect themselves. They reinforced the base’s bunkers and built new ones. They put up heavily meshed stand-off screens around the bigger bunkers. They set concertina wire out along the perimeter. They scattered homemade rudimentary mines filled with old truck parts outside the perimeter. They dug fighting holes around the compound. They pulled a lot of guard duty.

When they realized they were on their own, the men of the 299th used their engineering skills to try to protect themselves. They reinforced the base’s bunkers and built new ones. They put up heavily meshed stand-off screens around the bigger bunkers. They set concertina wire out along the perimeter. They scattered homemade rudimentary mines filled with old truck parts outside the perimeter. They dug fighting holes around the compound. They pulled a lot of guard duty.

“The business really started on May 9,” Zimmer said. On that day the NVA stepped things up considerably, enveloping the Dak To Defenders in a tight siege that didn’t end until the second week of July. During those two-plus months the NVA shelled the mountain virtually every day with 122mm rockets, 81mm mortar rounds, recoilless rifles, and B-40 rockets. Not to mention continued sapper attacks.

“The business really started on May 9,” Zimmer said. On that day the NVA stepped things up considerably, enveloping the Dak To Defenders in a tight siege that didn’t end until the second week of July. During those two-plus months the NVA shelled the mountain virtually every day with 122mm rockets, 81mm mortar rounds, recoilless rifles, and B-40 rockets. Not to mention continued sapper attacks. On May 20 Donovan Fluharty of Beaver, Pennsylvania, who was on guard duty that night on the perimeter with Gearhart and Terry Eutzy, was hit by a rocket and died five days before his 21st birthday. “I lost my best buddy,” Eutzy, a bulldozer operator from Lewistown, Pa., said. “He took a direct hit. He had a five-month-old daughter he never got to see.”

On May 20 Donovan Fluharty of Beaver, Pennsylvania, who was on guard duty that night on the perimeter with Gearhart and Terry Eutzy, was hit by a rocket and died five days before his 21st birthday. “I lost my best buddy,” Eutzy, a bulldozer operator from Lewistown, Pa., said. “He took a direct hit. He had a five-month-old daughter he never got to see.”

Another memorable incident took place in the morning of June 7. Glen Hickey, a draftee from Jefferson City, Missouri, who was working as the 299th CO’s jeep driver, described what happened in a letter he wrote later that day to his wife Gayle.

Another memorable incident took place in the morning of June 7. Glen Hickey, a draftee from Jefferson City, Missouri, who was working as the 299th CO’s jeep driver, described what happened in a letter he wrote later that day to his wife Gayle. With the ARVN refusing to fight, the 299th Engineers faced off against the NVA. Some used M-16s that they had taken from the ARVN. The fighting engineers drove off the NVA. Then they took the wounded back to the compound. A few hours later the minesweeping team was sent back out to the road.

With the ARVN refusing to fight, the 299th Engineers faced off against the NVA. Some used M-16s that they had taken from the ARVN. The fighting engineers drove off the NVA. Then they took the wounded back to the compound. A few hours later the minesweeping team was sent back out to the road.